Almost every language has a word for 'Christmas.' Few reference Christ.

A linguistic tour of holiday sayings, from Feliz Navidad to Mele Kalikimaka...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

¡Feliz Navidad! Joyeux Noël! Frohe Weihnachten! God Jul! Sretan Božić! Crăciun fericit! Priecīgus Ziemassvētkus!

How do you keep the Christ in Christmas if your language doesn't have a Christ in it to begin with?

The languages of the world have quite a variety of names for Christmas. That's not surprising, what with different languages having different words for things, but it turns out that our Christmas name stocking is stuffed with words that mean quite a few unrelated things. And many of them have nothing to do with Christ.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Christmas lands right at the same time as winter solstice festivals that were celebrated long before the coming of Christianity. That's likely an important reason Christmas is celebrated when it is: to co-opt the pagan festivals. (Jesus probably wasn't actually born on December 25. Scholars — including, in a 2012 book, Pope Benedict XVI — have raised many questions and made many suggestions about his actual birth date.) And Christmas isn't the only Christian celebration to co-opt pagan festivals: Hallowe'en and All Saints' Day take over from a fall festival, for instance, and Easter gets its English name — and those eggs and bunnies — from a pagan goddess, Eostre. Likewise, Christmas gets its trees and holly and mistletoe and even its gift-giving traditions from pre-Christian religious celebrations, and in many languages it gets its name from them too.

Take Yule, for instance (Old English spelling: Geol). Yule featured trees, logs, boars, carol-singing, and feasting at night. It appears in Scandinavian languages as Jul (or, in Iceland and the Faroe Islands, Jól) and was borrowed into Finnish as Joulu and Estonian as Jõulud — all now their words for Christmas. Yule was a festival of a holy night (or nights), and that's where German name for Christmas, Weihnachten, comes from: Middle High German wihen nahten, "holy night" (also converted by Czech into Vánoce). Oh, yes, it's holy for Christians too. It was easy enough to convert the festival to Christianity. Other nearby countries had winter festivals, too. In Latvian, Christmas is Ziemassvētki, which means (drumroll, please) "winter festival."

The Romans had a similar festival: the day of the birth of the unconquered sun. In Latin, that's dies natalis solis invicti. Just as the festival came to celebrate the birth not of the sun but of the son (of God), that word natalis, "of the birth," changed over time as Latin split into different languages. It became French Noël, Italian Natale, Spanish Navidad, and Portuguese Natal. Celtic languages also borrowed it: Gaelic Nollaig, Welsh Nadolig, and Breton Nedeleg.

Romanian also came from Latin, but in Romanian, Christmas is Crăciun, which is thought to come from Latin calatio, the name of a calling together of the people by priests — pre-Christian ones. Hungarian uses another version of the same word, Karácsony. In Lithuanian, Christmas is Kalėdos, which has an unclear origin but may come from the same source or a related one.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Birth shows up in other languages' names for Christmas, and it's not always easy to say whether the term started in reference to the birth of Jesus or whether it was carried over from a reference to a pagan birth (as of the sun god, for instance). In Polish it's Boże Narodzenie, "birth of God." Croatian Božić is a similar reference to God (or a god). Russian and Bulgarian are clear about whose birth it is: their name is Рождество Христово (Rozhdestvo Khristovo), meaning "birth of Christ." Albanian Krishtlindja means the same thing. So does Greek Χριστούγεννα (Khristougenna, which sounds to English speakers like "khristuyenna"). You'll notice that the Greek word starts with a letter that looks just like X. This is where Xmas comes from — English borrowed on an ancient scribal tradition of representing the Greek word Christos (Χριστός) with its first initial.

There are quite a lot of languages that have only needed a word for Christmas in fairly recent times. Some have used translations of "the birth of Jesus" or words to that effect — Mandarin Chinese 圣诞 shèng dàn means "birth of the sage." But many have gotten their word from whatever European language had the strongest influence on them at the time. Some use versions of Noel or Natal. Many use an adaptation of Christmas.

Ah, yes, Christmas. Our word comes from Old English Cristes mæsse, "the mass (liturgical celebration) of Christ." Dutch Kerstmiss comes from the same thing. Pretty much every other language that has a word with that origin got it from English or Dutch… and usually English.

In quite a lot of languages, though, "krismas" is not a possible sound combination. Some languages don't allow you to put the consonants together without vowels in between (so the Japanese version is Kurisumasu). Others don't use one or more of the sounds in the word. Thanks to Bing Crosby's song "Mele Kalikimaka," a well-known case of this is Hawai‘ian. Hawai‘ian doesn't have the sound "r" or the sound "s," and it doesn't allow two consonants to go together either. The closest it can come to Christmas is Kalikimaka, with l for r and k for s (k can also be said like "t" and possibly even "s" in some contexts, though no one told Bing that), plus some extra vowels. Yule would have been easier to work with…

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

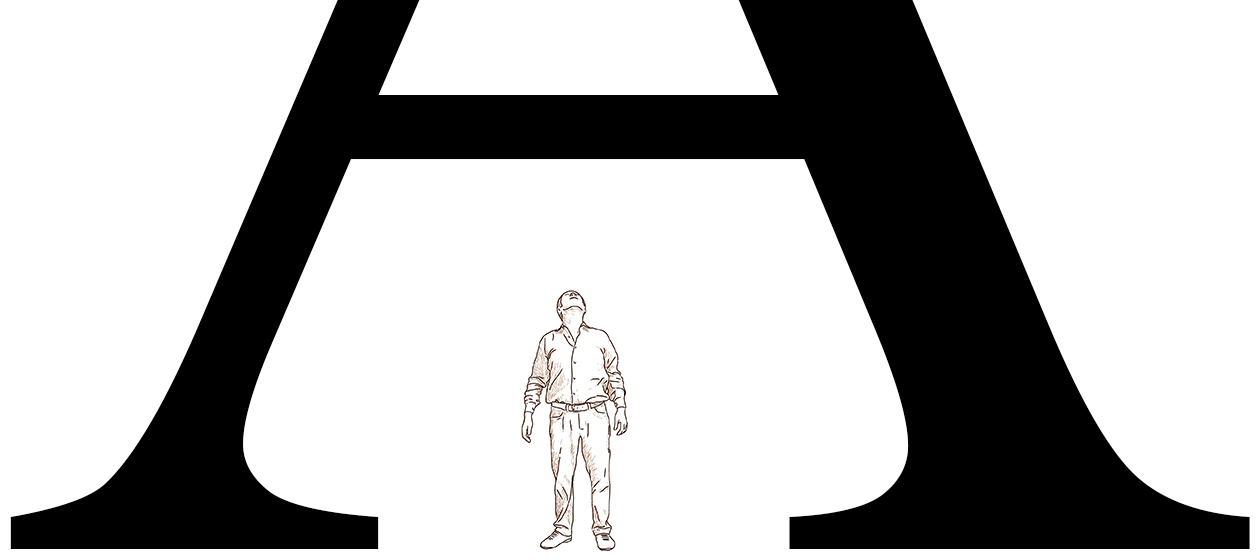

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

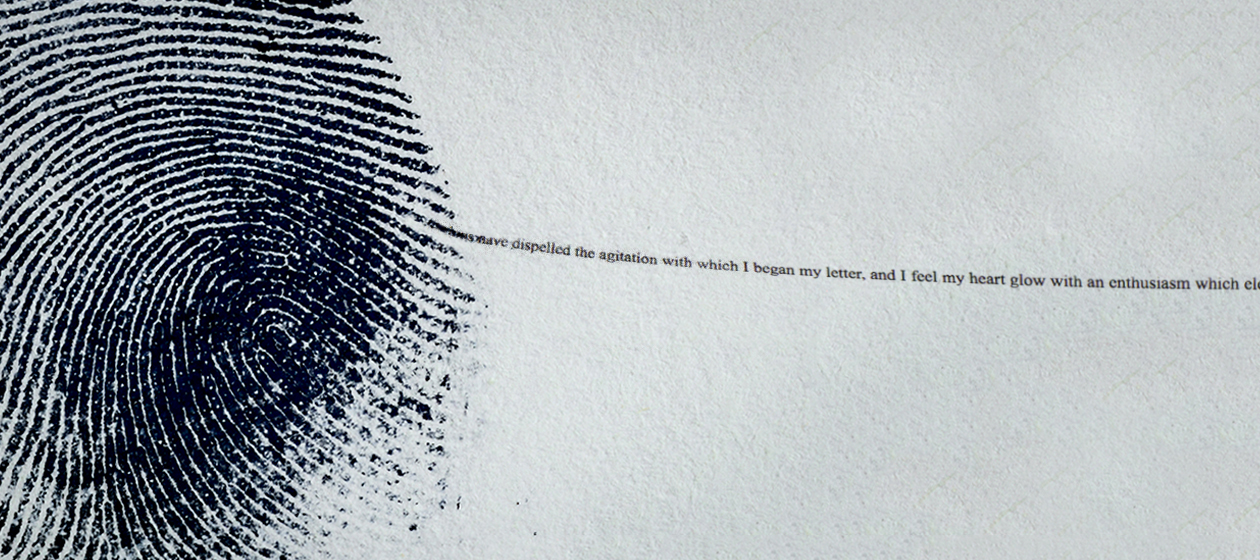

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

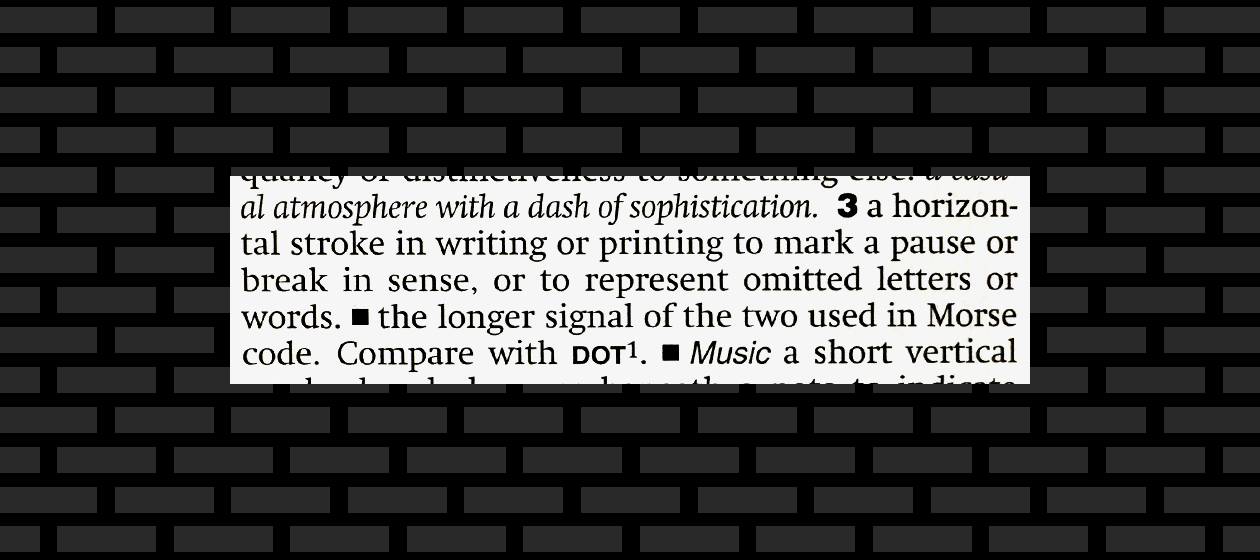

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.