A nuclear attack has never been more likely

Think we're safer than during the Cold War? Think again.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The West responded with a mixture of skepticism and condemnation when North Korea announced last week that it had detonated a hydrogen bomb. But even if it turns out that North Korea didn't create such a powerful nuclear bomb, and even if the country agrees to abide by nonproliferation standards to the letter, the world will still be at a historic high risk for nuclear disaster.

As former Secretary of Defense William Perry said last month, "we are facing nuclear dangers today that are in fact more likely to erupt into a nuclear conflict than during the Cold War."

Building a nuclear weapon requires technical know-how and rare materials that are fairly difficult to obtain. It makes sense that the two original nuclear powers, Russia and the United States, still have a monopoly on nukes. We've been honing our knowledge for much longer and have access to more of the necessary materials. In fact, the two countries combined account for 93 percent of the world's nuclear weapons. This fact might be comforting if the two biggest kids on the block hadn't resuscitated their enmity as of late — they theoretically could uphold their nonproliferation treaties, safeguard existing nuclear material, and assist other countries in destroying their own stockpiles. But that isn't what's happening. Instead, both America and Russia continue to develop nuclear capabilities, experiment with nuclear weaponry, and ignore dangerous nuclear waste.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In a recently leaked video, a Russian military commander peruses a document outlining the capabilities of the new "oceanic multi-purpose Status-6 system" nuclear torpedo. The weapon is designed to "destroy important economic installations of the enemy in coastal areas and cause guaranteed devastating damage to the country's territory by creating wide areas of radioactive contamination, rendering them unusable for military, economic, or other activity for a long time," according to the document as translated by the BBC. It's kind of an insane weapon, considering that that its range, at least according to the document, is 6,000 miles. As The National Interest points out, "that sounds more like an ICBM than a torpedo." It's also difficult to see how the weapon would be able to navigate the rocky ocean subsurface for that distance without running into a landmass and detonating. In other words, it's both provocative and dangerous.

But Russia isn't alone in developing new and dangerous nuclear weapons. The United States recently constructed the B61-12 guided nuclear bomb. The animating logic of America's nuclear deterrence arsenal has up until now been just that: deterrence. We maintain a stockpile of land, air, and sea-based nukes to prevent other countries from attacking America. But the B61-12 is different. With a sophisticated $178 billion tail-guidance system and "dial-a-blast" control function, it isn't meant to be used to assure mutual destruction, but as a low-yield tactical battlefield nuclear device. The problem with nuclear weapons that aren't big and dumb is that people will be tempted to actually use them. It takes nuclear weapons from an unthinkable last resort to a viable tactical option.

It's not just America's nuclear weapons that are dangerous. Having a nuclear arsenal creates a lot of nuclear waste that's dangerous to store and impossible to dispose of. Cleanup of nuclear waste at Los Alamos labs in New Mexico passed its deadline last month, leaving "radioactive and toxic waste stored on site, often in unlined pits, trenches, and shafts, and the contaminated buildings that housed lab operations." The situation in St. Louis, Missouri, is even scarier. An underground fire has been smoldering near an underground landfill for about five years. City officials warn that if the fire reaches nuclear material that's also buried underground, a legacy from the Manhattan Project, it could cause "radioactive fallout to be released in the smoke plume and spread throughout the region." Missouri state Senator Maria Chappelle-Nadal said on public radio that she's worried about the nearly 40,000 tons of buried uranium causing a "Chernobyl" like event, and "children who have double sets of teeth…missing eyeballs…brain tumors…" The fallout from such an event might be just as dramatic, if slower, than a nuclear attack itself.

Russia and America account for most of the nuclear weapons and material in the world, but other countries are flirting with disaster too. China, which has been building up its nuclear submarine fleet, and Pakistan, another nuclear power, are conducting joint naval exercises. India plans to build thermonuclear weapons in an underground city. And if the relative stability of the nation-state is enough to put your mind at ease, consider the risk of ISIS building a nuclear dirty bomb. According to former Senator Sam Nunn, that is "very likely to happen."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

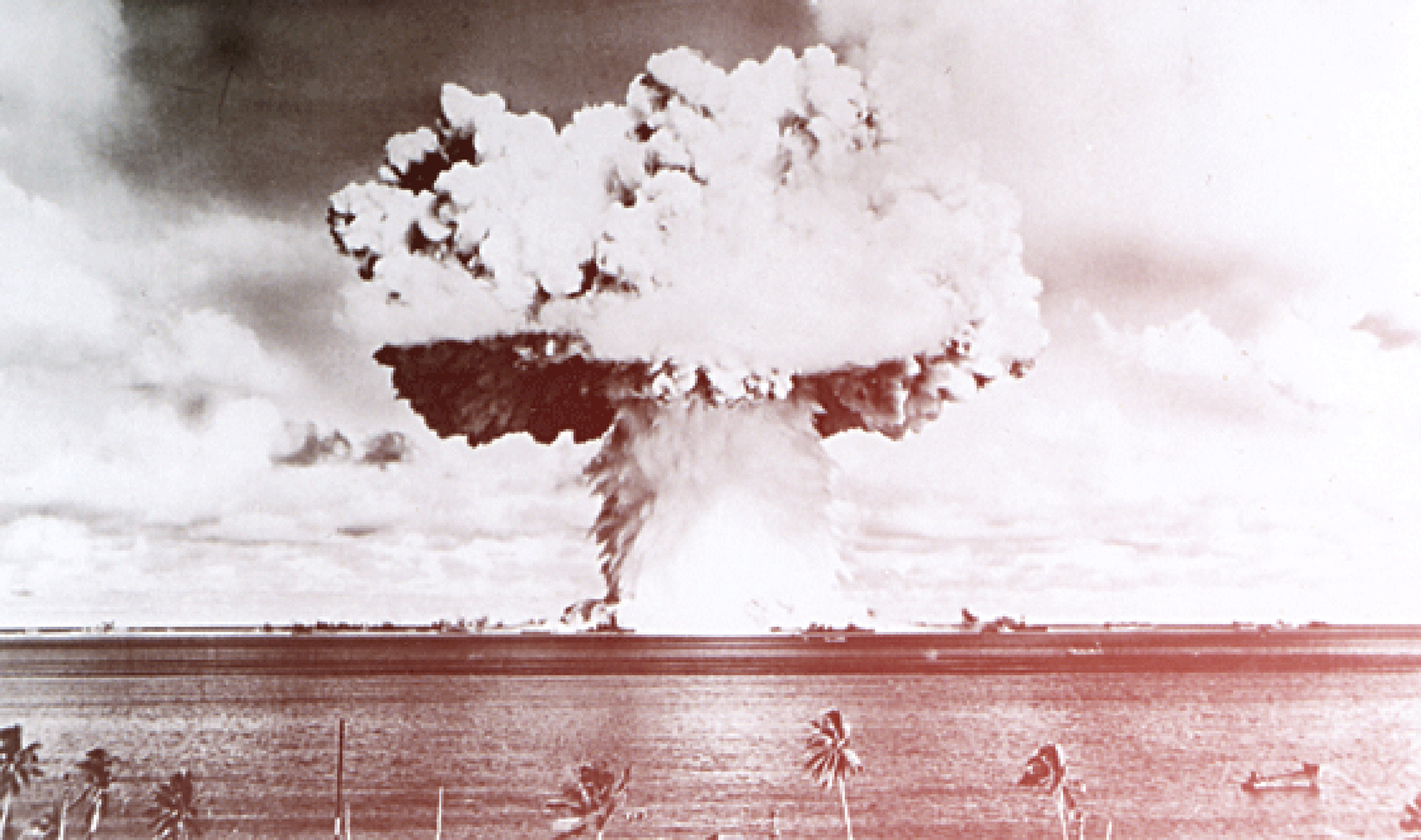

The world would be worse off if North Korea had an H-bomb, sure. The problem is it isn't that safe even if North Korea has no weapons. Last year, long before North Korea's announcement, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved its Doomsday Clock, a visual representation of the world's proximity to nuclear catastrophe, to three minutes to midnight. Last year also marked the seventieth anniversary of the first and, so far, only time nuclear weapons have been used in war. But we're still living in the shadow of the mushroom cloud.

Scott Beauchamp is a writer based in Portland, Maine. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, and The Paris Review, among other places.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military