'Government is the problem' and other Republican delusions

The GOP is now reaping the consequences of committing itself to a deranged ideology

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was the kind of joke you might hear from any Republican on the campaign trail in 2016 — from Donald Trump or Rand Paul, Chris Christie or Marco Rubio, or just about any GOP senator or House member, too. In this case, Ted Cruz told it. Recycling a line from his 2012 senatorial campaign, Cruz informed voters a week or so ago in Missouri Valley, Iowa, that the etymology for "politics" goes back to the ancient Greeks: "poly," for many, and "tics," for blood-sucking parasites.

Since he's used the line for so long, Cruz must have reason to think audiences like it. Yet I wonder whether anyone ever thinks to respond with what strikes me as an obvious question: "Since you're running for president, doesn't that mean that you're devoting every waking moment of your life to becoming the biggest blood-sucking parasite of all?"

There are many reasons why the Republicans have ended up in their current situation, with the two leading candidates (Trump and Cruz) threatening to tear the party apart. There's the nationalist backlash against elite disdain for borders and limits on immigration that's roiling democratic politics on both sides of the Atlantic. There's a nebulous mood of fear provoked by terrorism, mass shootings, the country's declining economic status in the world, and an endless news cycle that proclaims one crisis after another. And finally there's frustration about crumbling economic prospects among working-class whites that gets expressed as anxiety and anger about demographic and ethnic trends in the country.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But underlying these specifics is something more fundamental: nearly four decades of mounting rhetorical attacks on Washington, government, and even politics itself by Republican politicians and their cheerleaders in the old and new media.

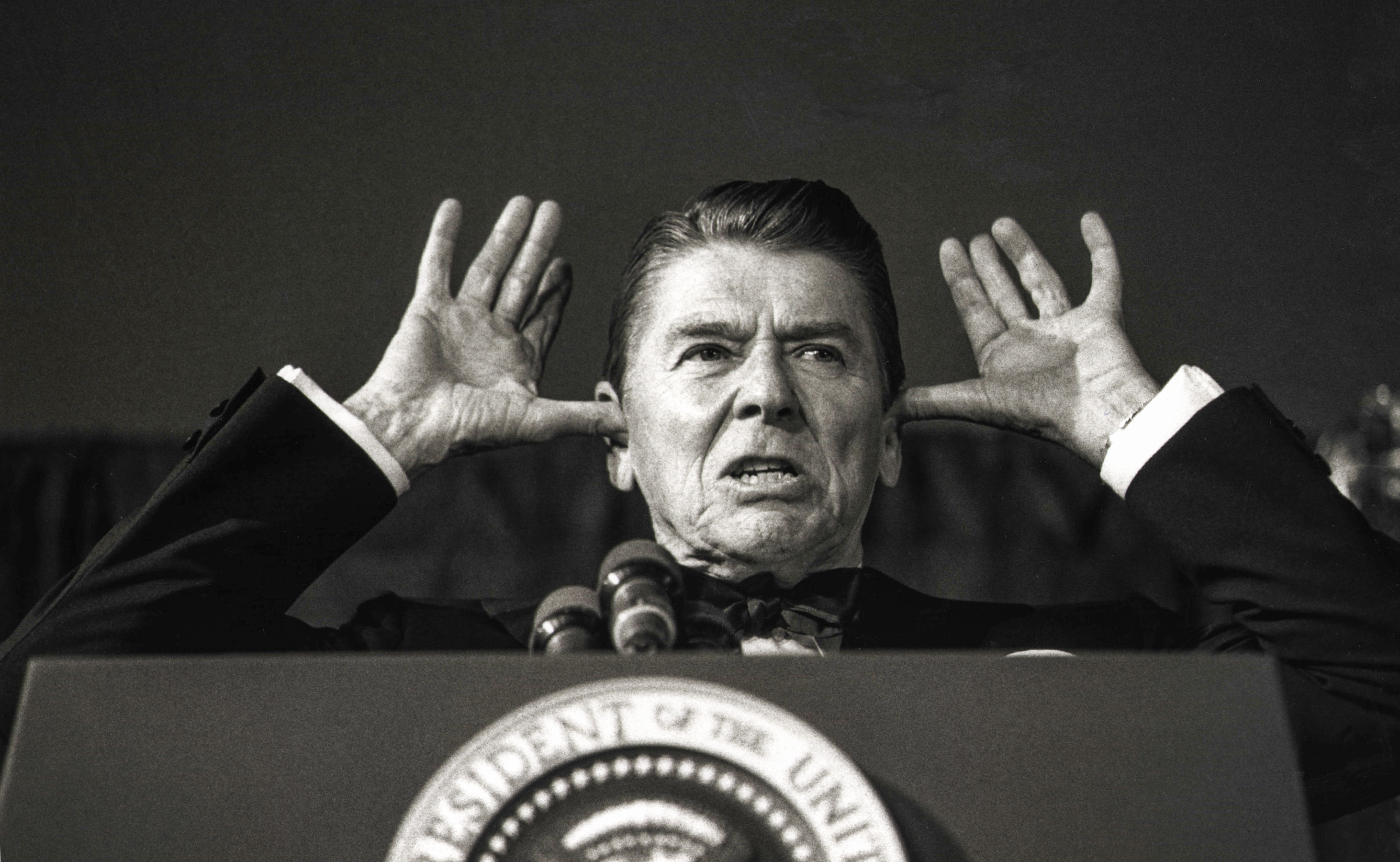

Though it may sound like heresy to many if not most Republicans these days, the anti-government impulse, which is now treated like inerrant doctrine rooted in an infallible Reaganite revelation, is a delusion tinted with outright paranoia, a judgment lacking historical perspective or international context. Democrats and reasonable Republicans don't say it nearly enough: The GOP is reaping the consequences of having committed (and repeatedly recommitted) itself to an anti-government ideology with only the most tenuous connection to reality.

The United States has an old and venerable history of suspicion toward government power going back to Jefferson and Paine, if not before. Reagan's political genius was to take up and revive this tradition, deploying it as a grassroots ideology at a time when the message made sense. The 1970s saw price controls, vast swaths of the economy regulated to an extent Americans today can barely imagine, a top income tax rate of 70 percent, and rampant and persistently high inflation, double-digit interest rates, and painful levels of unemployment, all of which seemed to demonstrate the economic incompetence of policymakers.

This was the backdrop to the Reagan revolution — and why it suited the moment. Republicans love to quote The Gipper's first inaugural address and its declaration that "government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem." But few bother to note that this statement was preceded by a qualification: "In this present crisis.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yet the ideology persisted, and became more radical and less tied to reality, even after it had won every battle it was forged to fight — even after taxes were slashed, regulations cut, stagflation eradicated, and growth revived. That's because anti-government ideology provided the Republican Party with an incredibly useful, versatile scapegoat. Whatever the problem in the country, and even when there was no significant problem at all, voters could be mobilized against "the government," an enemy that could never really be defeated and so was always present to serve as an all-purpose object of blame and abuse.

Republicans now even had an incentive to govern irresponsibly, since any suffering they caused (or refused to alleviate) could be used as evidence to confirm the anti-government ideology in the next round of elections. ("See how bad government is? Elect me, and I'll cut taxes and spending even further!")

The dynamic played out most recently after the 2010 midterm elections, when the new Republican majority in the House of Representatives imposed austerity budgets in the immediate aftermath of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Spending cuts slowed the economic recovery, which was then used during the 2012 election cycle as evidence against Obama's "big government" policies.

And that brings us to the ideology's only political downside for Republicans: Like all revolutionary programs, anti-government fervor has a tendency to devour its greatest heroes and champions.

When politicians go to Washington to slay (or starve) the beast, they later become easy targets for challengers who gleefully accuse them of having gone native by compromising with the "statism" that supposedly infects the nation's capital. That necessitates a new round of even more radical revolt against government. And then another. And another. Trump and Cruz are slightly different variations on what happens when the revolution turns on itself.

Is government perfect? Of course not. Is it sometimes inefficient? Certainly. Could it benefit from reform in some areas and cuts in others? Without a doubt.

But that simply isn't the whole story. Compared with rates of government corruption and inefficiency in other countries around the world, the federal government of the United States does its job quite admirably — and without placing an unreasonable burden on the economy. (In 2008, before the economic crisis hit, federal outlays stood at 20.3 percent of GDP. Spending understandably and appropriately jumped to 24.4 percent in 2009, at the lowest trough of the recession. But by 2015, outlays had come most of the way back down, to 20.7 percent. A temporary recession-related spike in the deficit has also been resolved.)

Meanwhile, Obama's stewardship of the economy — including the passage and implementation of the Affordable Care Act — has gone fairly well overall. Fourteen million jobs have been created since 2009, and millions more people are now covered by health insurance. And none of the nightmare scenarios predicted by anti-government Republicans — from spiraling health care costs to painful job losses — have materialized. As a law, ObamaCare isn't pretty, and neither was its passage. But it works — not perfectly, but decently. Six years after it was signed into law, it's a modest net plus for the United States.

Viewed without an a priori anti-government filter, America in 2016 is a place that cries out for more government spending and oversight, not less. From guns to the environment to the financial services industry to, yes, health care, the United States is a country seriously under-regulated.

The U.S. needs two viable and vibrant parties. It's a good thing for Democrats and Republicans to disagree sharply about how best to tax, spend, regulate, and pursue the public interest.

What the country very much does not need is for one of those parties to refuse to participate in the debate because it's become hostage to the insidious idea that when it comes to government, less is invariably more, and nothing at all must be the very best of all.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.