Can the big political parties harness the energy of their populist insurgencies?

It sure doesn't seem like it...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ted Cruz lost in Mississippi. John Kasich fanned in Michigan. Marco Rubio all but collapsed, not even close in Idaho, where some hoped he might make a mark.

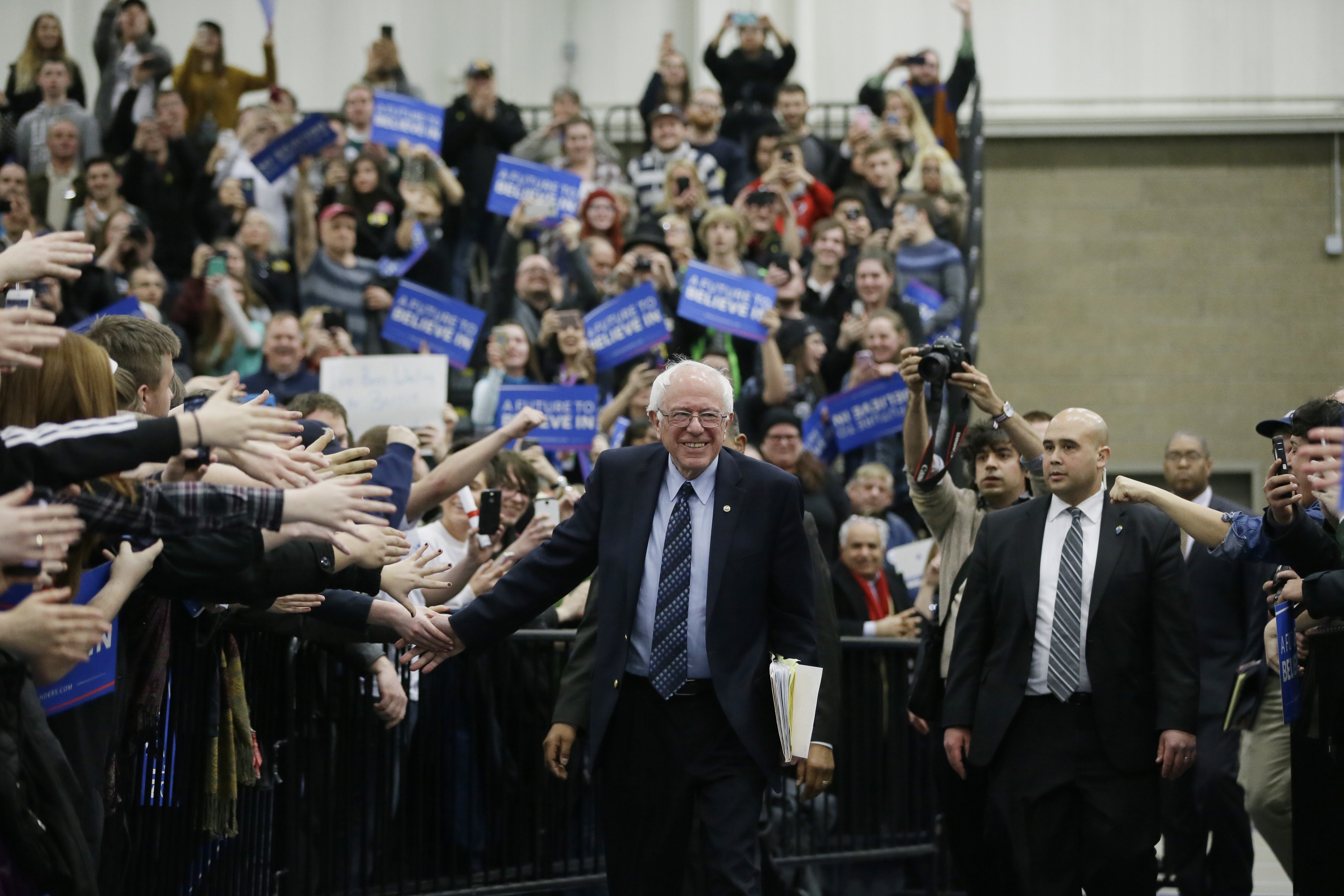

And then there was Bernie. In a shocker that broke the spirit of pollsters everywhere, Sanders overcame a wide double-digit deficit to squeak out a stunning win over Hillary Clinton in Michigan.

Tuesday night's primaries and caucuses carried a clear lesson: Voters are unhappy. They who have felt so punished are now proceeding to punish.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So the big question shaping up for party elites on both sides is the same: What will it take to overcome these populist insurgencies? What will placate the insurgents, or negotiate a workable peace, and bring them back — energy intact — into the campaign fold? If the established parties can figure this out, the dividends could make the difference between success and failure in the general election. Democrats' turnout has crashed this year relative to last cycle; they need voters to feel as much of a burn (or Bern) as possible. And though Republicans have enjoyed blockbuster turnout, if they manage to deny Donald Trump the nomination, they could face enough of a rebellion to vault Clinton comfortably into the White House.

Sometimes instant conventional wisdom turns out to be correct, and a plausible narrative about how to placate the insurgents has already started to shape up. For Republicans and Democrats alike, in fact, it's just about the same: Sanders and Trump have tapped into voters who don't like free trade. While Bernie's brigades blew away expectations thanks to Michigan's industrial base, Trump beat back Kasich and Cruz by sticking out as the one guy who rejects the negative Beltway view of protectionism.

But can anyone imagine either party nudging an inch on trade? The pro-corporate consensus powering global trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership is not overwhelming — after all, the TPP is still tied up in Congress — but it is strong enough to ensure its dominance even in a year with so much populism from left to right. What's more, the consensus is as strong as it is because elites know the consequences to our still-fragile international financial system if tariffs and trade wars become the next big thing. They're just unlikely to reconcile with their respective insurgencies on the flows of goods and services that shape the global economy.

That means they need to horse trade in some other way — or face the electoral consequences.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The major issue adjacent to trade is labor. It's the changing dispensation of workers and jobs that's behind the immigration animosity rankling Republicans, and it's the political touchstone for anti-corporate progressives who don't believe card check is more important than unions. Conceivably, either party could try to renegotiate their political compact with an economic platform that at least tries to protect American jobs if not protect favorable business conditions. But this too seems dead on arrival. An economy structured around growth for the cheapest and costliest wages can only be twisted so much to the advantage of the working and lower-middle classes. And neither party really believes they can make up in support among the despairing that they have lost with the merely anxious.

If trade, labor, and immigration are out, it's hard to find one realm of policy where America's insurgents are crying out for change and America's established leadership might be willing to change. Unless, of course, you look to the last big zone of economic politics — the financial industry. Hark back to Rick Perry's campaign, and you'll discover that the ballyhooed Texan actually rolled out a fairly serious plan for reforming Wall Street. Look ahead, meanwhile, and Elizabeth Warren will still enjoy the stalwart support of Democrats dissatisfied by Clinton's moneyed habits — and energized by Sanders' finance-focused campaign.

Perhaps the only way the party bigs can bank on a lasting victory in November is by turning, at long last, on the big banks. If not, today's bipartisan insurgency is set to drag on — with a deeper victory than Election Day staying stubbornly elusive.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Key Bangladesh election returns old guard to power

Key Bangladesh election returns old guard to powerSpeed Read The Bangladesh Nationalist Party claimed a decisive victory

-

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over video

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over videoSpeed Read Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth pushed for the senator to be demoted over a video in which he reminds military officials they should refuse illegal orders

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred