The sneakily progressive feminism of Cosmopolitan

Where would we be without Helen Gurley Brown's sex-loving brand of feminism?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You've probably got the wrong idea about Helen Gurley Brown.

The conventional wisdom around Brown, the author of Sex and the Single Girl, and the long-time editor of Cosmopolitan magazine, was neatly summed up recently by Rebecca Traister in her new book All the Single Ladies. Brown was in the business of talking to "unmarried, sexually adventurous women," Traister wrote, who Brown thought were "motivated largely by their hunt for husbands" but ought to "be having fun and feeling good about themselves along the way."

This reputation as a rather jaunty woman not to be taken seriously by Serious People dogged Brown throughout her career. While at Cosmopolitan, her critics and colleagues dismissed her as a hack, an imposter, and "just a woman who wrote a sex book." Brown herself often helped peddle this shallow narrative during her rise from office secretary to editor-in-chief of America's bestselling magazine for young women.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But that's not all Helen Gurley Brown was. She was ambitious, generous, wildly insecure, and a hard-working champion of women. She was one of the most influential feminists of her time, pioneering a mini-skirted brand of girl power that showed women they can and should have sex, desires, and a full and productive life, just like men.

Brooke Hauser's excellent new book Enter Helen takes us from the inception of Helen Gurley Brown's Sex and the Single Girl through her retirement from the magazine publishing world at the age of 75, and death in 2012, with several time-jumping detours into Brown's humble post-Depression childhood in Arkansas, her lonely teenage years, and her early career days in Los Angeles' hungry advertising industry.

Even as a teenager, Brown knew she wanted more than the housewife life that was prescribed for young women at the time. Though she was an excellent student, Brown gave up her chance at a college education to care for her polio-stricken older sister and widowed mother. What she lacked in formal education, however, she made up for in plucky ambition. When she moved to Los Angeles and out on her own at the age of 24, she dove into the workforce. By the time Sex and the Single Girl came out in 1962, Brown had worked her way through 17 different secretarial jobs to become one of the highest-paid female copywriters on the West Coast.

At the age of 37, Brown married a successful Hollywood producer named David Brown, who saw potential in his wife's writing, and pushed her to write a book about her single years. David first envisioned Brown's book as a "cutesy manual for girls who wanted to get rid of the extra men in their lives so that they could home in on Mr. Right," Hauser writes in Enter Helen, "but as Helen jotted down more and more notes about her days as a bachelorette, she realized that she was tapping into a much bigger theme: the stigma of the single woman."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As Hauser details, Sex and the Single Girl was about much more than salacious chapter titles like "How to be sexy" and "The affair: From beginning to end." The progressive 1962 book also offered a step-by-step guide to breaking free of societal norms and constraints. The idea that young women could live fully without dutifully devoting themselves to marital sacrifice was revelatory. Using the tone of the wise, older sister who's been through it all, Brown wrote frankly about men and sex, but also about the logistics of living alone — how to care for your finances and advance in your job, and the importance of having your own space ("Roommates are for sorority girls").

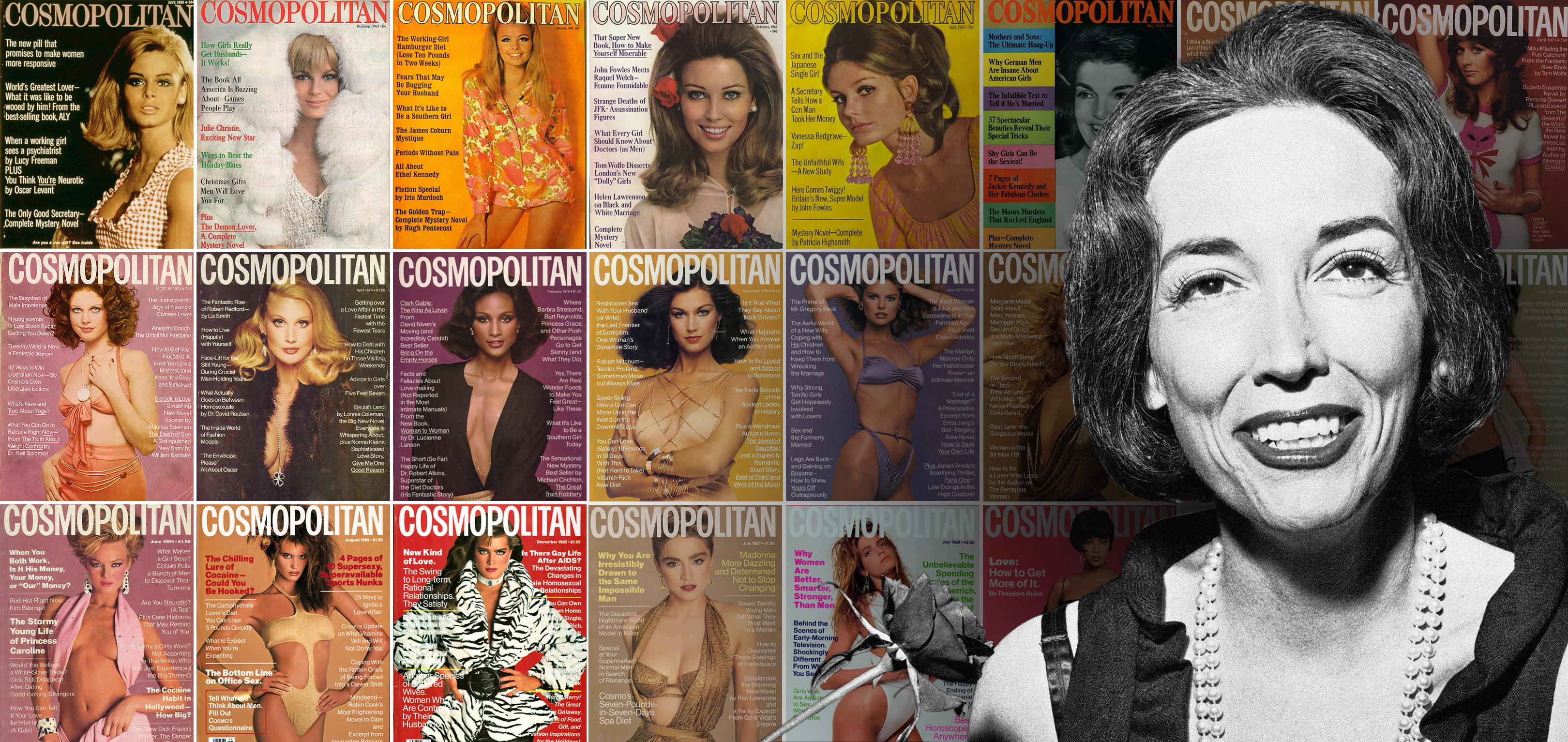

Of course, Brown reveled in the sexy stuff, too. She yearned to be beautiful, and developed an obsession with beauty that would show itself in the stunning, busty cover models of Cosmopolitan. If you had it, Brown believed, by all means, flaunt it. But she also knew that you didn't have to be Hollywood attractive to feel beautiful under a man's gaze. Sex, it turns out, was just as powerful a captivator. "So she didn't look like Jane Russell — she didn't need to once she got a man alone with her," Hauser writes. "She liked to talk dirty, a bit of a novelty in those days, and her orgasms were usually real. Nothing was more exciting or flattering to the ego than being in the tight grip of a man who wanted her."

Sex gave Brown confidence, something, she recognized, that all women could use to even the playing field. If women weren't doing it already, she believed, they should be made to feel sexy, enjoy sex, and have loads of it, just like men. "Theoretically a 'nice' single woman has no sex life. What nonsense!'" Brown wrote in Sex and the Single Girl. "She has a better sex life than most of her married friends. She need never be bored with one man per lifetime. Her choice of partners is endless and they seek her. They never come to her duty-bound. Her married friends refer to her pursuers as wolves, but actually many of them turn out to be lambs — to be shorn and worn by her."

Brown proved not only that single women were an eager and underserved audience with real buying power, but also that she had a unique talent in speaking to them. She continued to be a voice for single women with her follow up, Sex and the Office, as well as her regular newspaper column, Woman Alone, which she used to field questions from her fans. And when Brown was hired in 1965 to helm the floundering literary magazine Cosmopolitan, she dedicated its pages with single-minded focus to her vision of the Cosmo girl.

"Other people might have seen that girl as someone's bored secretary, unmarried daughter, insecure friend, or dissatisfied wife," Hauser writes, "but Helen spoke to the person she was on the inside. She saw her for who she truly was — a woman with desires as strong as a man's."

Brown personally selected articles and cover models — and curated advertisements — for this busy, ambitious, and flirtatious young woman who was attempting to climb the career ladder while keeping her sweat under control and her cramps manageable. Brown balanced the practical ("How to avoid a disastrous divorce"; "You can own your own home — even if single and not rich"; "42 ways to win liberation now — by Cosmo's own liberated editors") with the sexy and aspirational ("Legs a man can't forget — they can be yours"; "Sex-ercise: to make your body sensually catlike — and keep him purring"; "How to travel in style when single").

It worked. The first Brown-helmed Cosmopolitan magazine, which came out in July 1965, sold 260,000 more copies than the June issue did. Within months, Cosmopolitan was reaching the one million mark and bringing in a torrent of new advertising.

To Brown's harshest critics, Cosmopolitan was "quite obscene and quite horrible" and "one of the most body-shaming, insecurity provoking, long-lasting sexist media products of the last 100 years." But to the hundreds and thousands of women who became loyal readers, it was a revolution.

To many single women of the '60s, Brown was just about the only person who stood up for them, who represented them, who understood them. But in the 1970s, things changed.

In 1971, Gloria Steinem launched Ms., suspecting there was an eager audience of young women looking for a magazine that informed them about social and political issues directly affecting their lives, alongside features on topics from abortion to race relations. Women responded. The first edition of Ms., which ran as an insert in New York magazine, helped the issue set a newsstand record.

Ms. and Cosmopolitan were positioned as opposites. While Ms. was exalted for reporting on and advancing women's rights, Cosmopolitan was dismissed by many critics as a setback for the gender, positioning women as sexual objects whose sole purpose in life was to find a man.

"Nobody took it seriously, let's face it," Steinem said of Cosmo. "I mean, I would always fight for it on the grounds that it was at least allowing women to be sexual, even though it was to gain approval, and it wasn't exactly self-empowered.'"

And yet, the two brands were similar, both in their fiercely loyal readership, and, beneath their wildly different covers and headlines, the message that women should be free to pursue their lives independently and fully. "Both magazines had broken the mold of the traditional women's glossy and both were revolutionary," Hauser writes, "advocating for equal rights in the bedroom and the boardroom."

Today, Cosmopolitan has more than 3 million readers and continues to honor Brown's "sex-loving brand of feminism" with a mix of practical and flirtatious advice, serious and informative features, and beauty and style coverage for the young, busy career woman. In the April 2016 issue, for example, you can read about women who are putting their newborns up for adoption to gay couples, sex tips for when you're sleeping with someone new, how to keep your apartment clean in less time, how to have a safe abortion, and the women who are breaking into the boys club of the tech world.

Brown stood up for women, but she did it her way, and on her terms. Brown believed that women should freely pursue careers and sex, just like men, and enjoy how they looked and felt while doing it. This is certainly a feminist view — but it's just one of many. There's also Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, Erica Jong and Roxane Gay — heck, even Candace Bushnell. The message of feminism today is sung by a resounding and diverse chorus of women, each belting out from a different songbook.

Feminism is not a monolith, nor is it a scale with the Cosmopolitan reader on one side and a Ms. reader on the other. Feminism is, rather, a kaleidoscope, where the desires of one readership mesh with the desires of another, colliding and diverging beautifully with the changing light, becoming something new entirely. And we have Helen Gurley Brown to thank for that.

Lauren Hansen produces The Week’s podcasts and videos and edits the photo blog, Captured. She also manages the production of the magazine's iPad app. A graduate of Kenyon College and Northwestern University, she previously worked at the BBC and Frontline. She knows a thing or two about pretty pictures and cute puppies, both of which she tweets about @mylaurenhansen.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

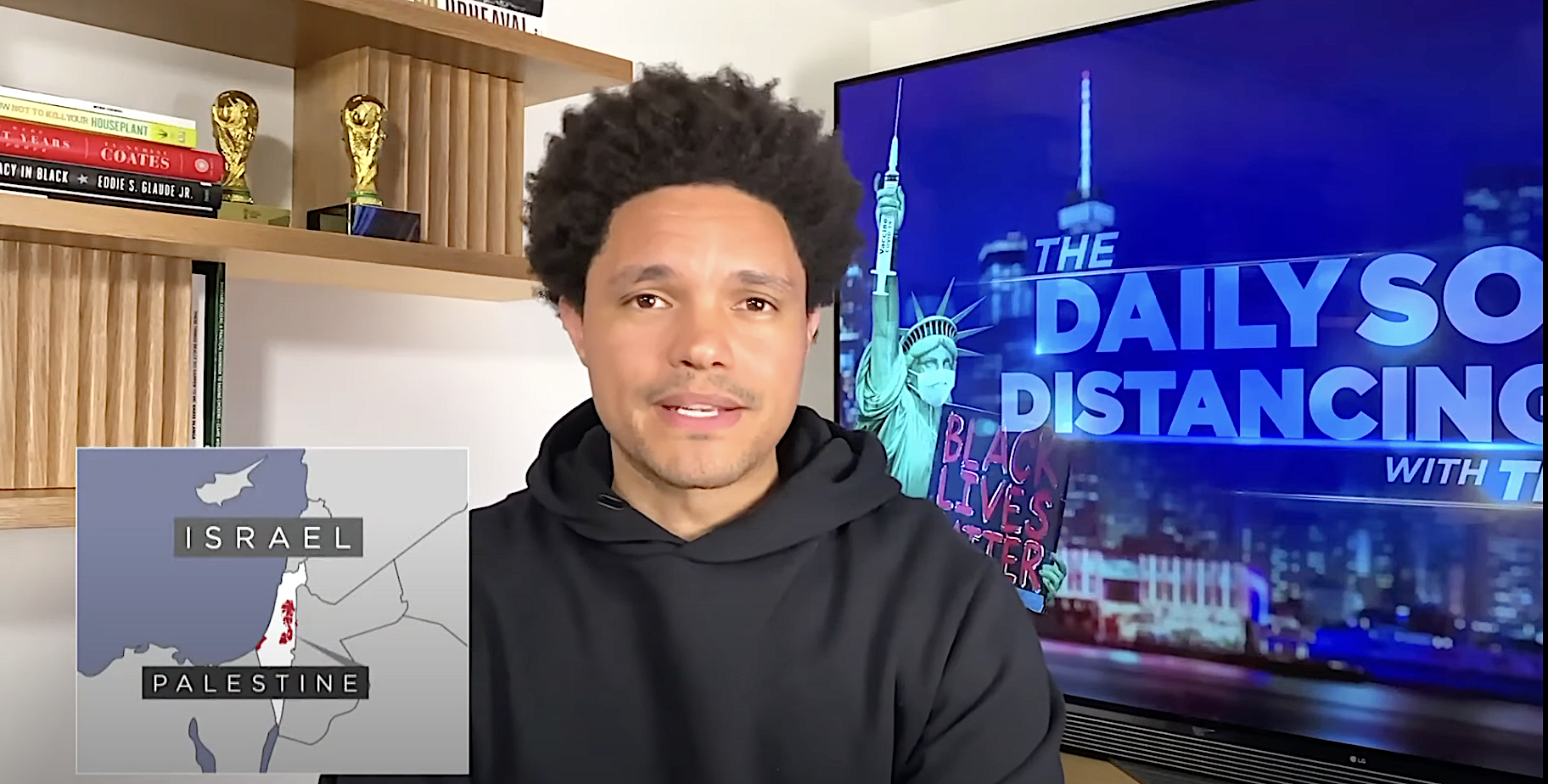

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white people

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white peopleSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar pains

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar painsSpeed Read