Why the West needs a more united Europe

Europe's need for real unity exceeds the EU's feeble powers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

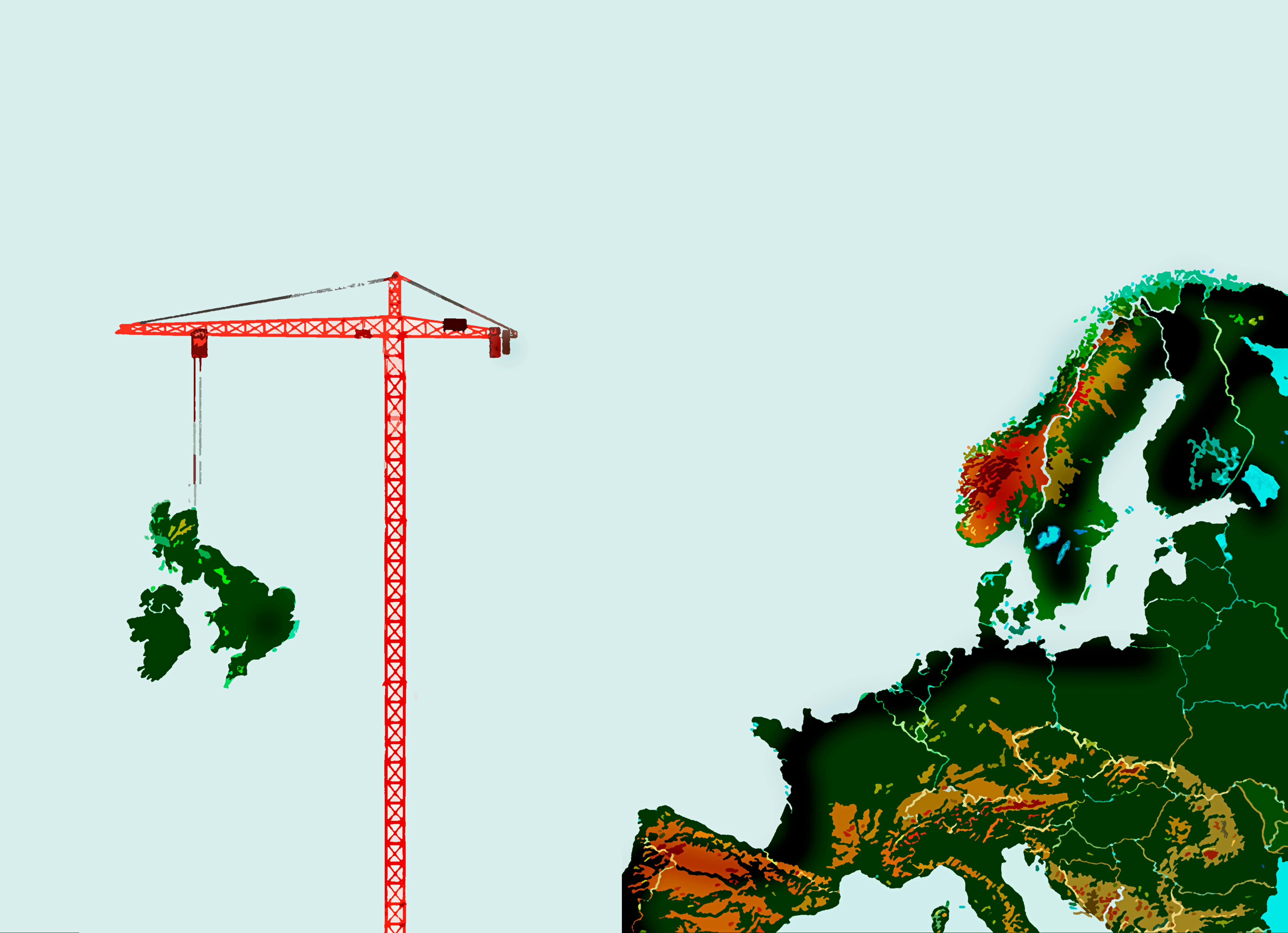

With Britain sharply divided over the wisdom of bailing on the shaky European Union — that "Brexit" will be put to a vote on June 23 — former London Mayor Boris Johnson warned the Telegraph that the continent's motto ought to be Divided We Stand. "Napoleon, Hitler, various people tried this out," he said of unification in scary times, "and it ends tragically. The EU is an attempt to do this by different methods." Different than, you know, armed invasion and conquest.

Weak and overweening as the EU may be, it's the least of Europe's problems. The flood of refugees opened up by the Syrian conflict is a bonanza for terrorists. Recruitment efforts have homed in on Europe's most promising and vulnerable targets — not just Muslim ghettos but whole countries, like Bosnia, where Western officials are scrambling to head off another front in the unfolding worldwide war. And that's to say nothing of autocratic Turkey's demand of billions in cash to handle refugees of its own, or Russia's intensifying provocations.

Europe cannot handle these problems nation-state by nation-state. Even the best prepared of its more powerful members (France, Germany, and that's probably it) are struggling — hemorrhaging money, straining to keep their heads above water on crime and terror, and facing down deepening political fractures at home. Britain has never been part and parcel of Europe, but it's rash for even an Englishman to raise the specter of a quasi-Hitlerian bureaucracy. Unled, Europe is primed to charge off in all directions — a messy and likely bloody process historically hard to stop once it begins.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Europe's need for real unity exceeds the EU's feeble powers. To be sure, we can all breathe a sigh of relief that today's continentals lack both the revolutionary fervor that helped out Napoleon and the reactionary derangement that fueled the Nazis' march. But in the absence of these ideological obsessions, Europe has struggled to channel its energies toward a single dynamic goal. Even NATO — still absolutely essential to holding the West together in a position of strength — was a defensive alliance, one that expanded eastward mostly out of concern that if it did not then it wouldn't know what to do.

If history is any guide, there may be a dark comfort in crisis. The West has proven remarkably resilient in the face of disaster. Judging by the seething hatred and anger fueling much of Europe's extremist politics, the warlike spirit that has long haunted the European conscience is probably much farther from extinction than many would like to admit. There is a chance that, if things continue to take a dire turn and the EU finds itself helpless, that energy can be channeled away from debilitating civil war or cross-border conflict and toward a muscular but recognizably humane effort to restore order.

This would require some kind of broad coordination, some prime mover, some leader with authority and operational control. Who is that? Not Angela Merkel, whose troubles have been crystallized by the surprise discovery of a severed pig's head, written with insults, outside her constituency office. (It's the second such head — associated with disapproval of her refugee policy — to makes an appearance this year.) And not the likes of Marine Le Pen — who hopes to forge a de facto alliance among Europe's right-wing nationalists, but who shows no interest in putting European leadership at the top of France's agenda.

Europe faces a basic chicken and egg problem. No leader to create the unity that is needed, and none of the popular consensus that might push such a leader to the fore. As dire as the threat posed by Russians and Islamists will become, not even the U.S. can save Europeans in disarray from their own worst enemies: themselves.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military