Brexit's clearest lesson: Referendums are never, ever a good idea

It isn't democracy at its best. It's a tool used by responsibility-shirking leaders who want to wriggle their way out of difficult decision-making.

The people of Britain voted to leave the European Union, but they should never have been given that power. Referendums are a manifestation of lazy government — a tool used by responsibility-shirking leaders who want to wriggle their way out of difficult decision-making.

Now, a newly severed, internally fractured U.K. faces years of political and financial instability as it tries to find its feet. It's a spectacular mess, created entirely by British Prime Minister David Cameron. He called the referendum in 2013, not because he believed Britain's EU membership needed to be debated but to shore up his own power base. The prime minister thought he could placate the vocal Euroskeptic wing of his Conservative Party, and woo voters away from the anti-immigration U.K. Independence Party, by announcing a referendum he was confident he could win. But his political gamble backfired, costing Cameron — who headed the Remain campaign — his job and legacy. Britain will pay a much steeper price.

On the surface, referendums seem like a good thing: Democracy delivered in its purest form. In reality, they're a convenient way for leaders to pass decision-making responsibility back to the public — as and when it suits them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Australia's Conservative Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has promised a plebiscite on legalizing same-sex marriage if he wins this week's general election. It sounds like a bold move but in fact it's a deeply cowardly one. The referendum will cost taxpayers an estimated $380 million, and is entirely pointless because polls have repeatedly shown that more than two-thirds of Australian voters back marriage equality. Turnbull, who supports gay marriage rights, could have just put forward legislation and allowed parliament to vote on the issue. But he doesn't want to alienate his social conservative supporters, so instead he's punted the task of lawmaking to the public.

Of course, it's easy to be tricked into thinking referendums are a good idea when enough of them produce results that fit with your worldview. Sometimes, plebiscites can deliver a righteous slam-dunk, like with Ireland's same-sex marriage referendum last year. There, everything went right: 61 percent of the population turned out to vote and a discriminatory law was thrown on the trash heap. Similarly, Scotland's recent referendum on whether to stay part of the U.K engaged young people and boosted the morale of a population that felt like it was being ignored by the London Parliament.

But, a single "bad" referendum result, like the U.K.'s Brexit vote, instantly makes those virtuous, earlier referendums look less like positive examples of direct democracy and more like foolhardy bets that just happened to pay off.

Complex electoral systems evolved largely to make sure that the public is heard, but doesn't have entirely proportional control. This is far from a perfect arrangement, but ultimately it ensures that the nuanced — and often boring and mind-bogglingly complicated — minutiae of governing stays in the hands of those officials elected to handle it. If you're lucky enough to live in a high-functioning democracy and don't like what you see then you can campaign, lobby, or stand for office. Referendums make a mockery of evolved democracies that, largely, manage to filter out extremist candidates and ideas. Democracy, like most ideologies served undiluted, is toxic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

America doesn't hold referendums on a federal level, but this country isn't immune from plebiscite rot. Just look at California, where in 1978 nearly two-thirds of the state's electorate voted to pass Proposition 13, which cut property tax rates on homes, businesses, and farms by about 57 percent. It was a disaster for state finances, and the consequences of that display of people power can still be felt today.

Referendums can also disproportionately exaggerate an issue: Europe wasn't a big, contentious deal in the U.K. until the vote was announced in 2013. Britain's EU membership went from a marginal issue, obsessed over by a few extreme right-wingers, to a symbol of everything that's wrong with the country. Millions of my fellow Britons, ever eager to spit scorn on something or someone, went to town. In the frantic months leading up to the vote, economists scrambled to educate the public on this once niche matter. The vast majority warned loudly that a Leave result would have dire consequences. But it was too late; most Brits weren't listening. "I think people in this country," said prominent Leave campaigner and Tory MP Michael Gove, "have had enough of experts."

Ironically, other Europeans, the people from whom we Britons apparently feel so removed, love holding referendums. They're on the rise, with an average of eight taking place each year compared to just two a year in the 1970s. In the coming months, both Italy and Hungary will hold referendums, the latter in an attempt to undermine EU immigration law. Switzerland, meanwhile, is a referendum powerhouse, having already held nine in the first half of 2016, with more to come.

But ultimately, calling a mass vote on single issues tells the public that the political establishment lacks faith in their own judgment. It says, "We don't trust ourselves to lead." With this message tacitly underpinning every referendum, it's no wonder that the British public refused to side with their government.

-

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

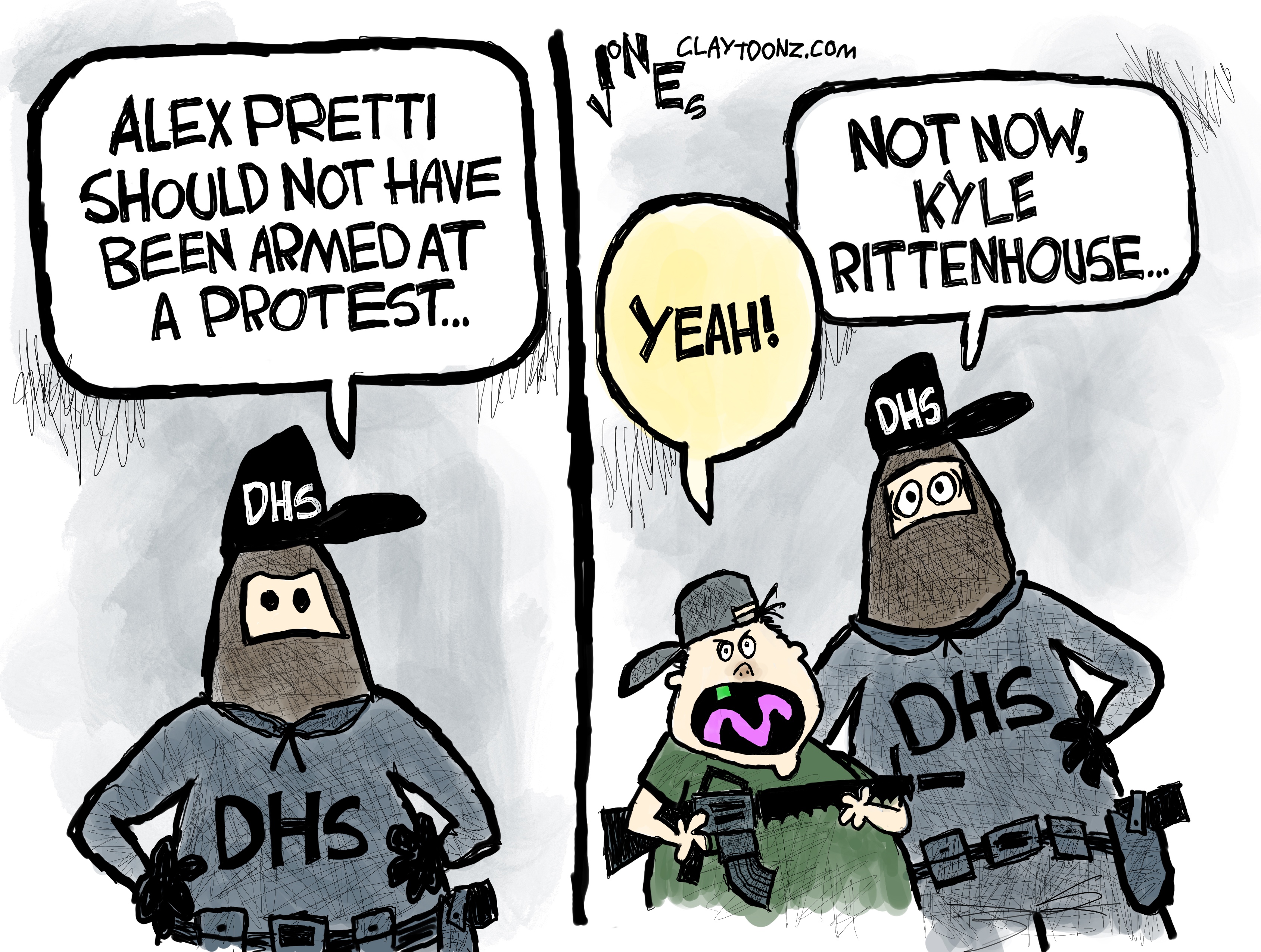

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aid

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aidIn the Spotlight AI has enabled the scam to spread into community colleges around the country

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military

-

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protests

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Femicide: Italy’s newest crime

Femicide: Italy’s newest crimeThe Explainer Landmark law to criminalise murder of a woman as an ‘act of hatred’ or ‘subjugation’ but critics say Italy is still deeply patriarchal