European elites desperately need a dose of sanity

Italy's failed referendum sends a strong message to the elite: Wake up and listen to the people

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Another political earthquake out of Europe!

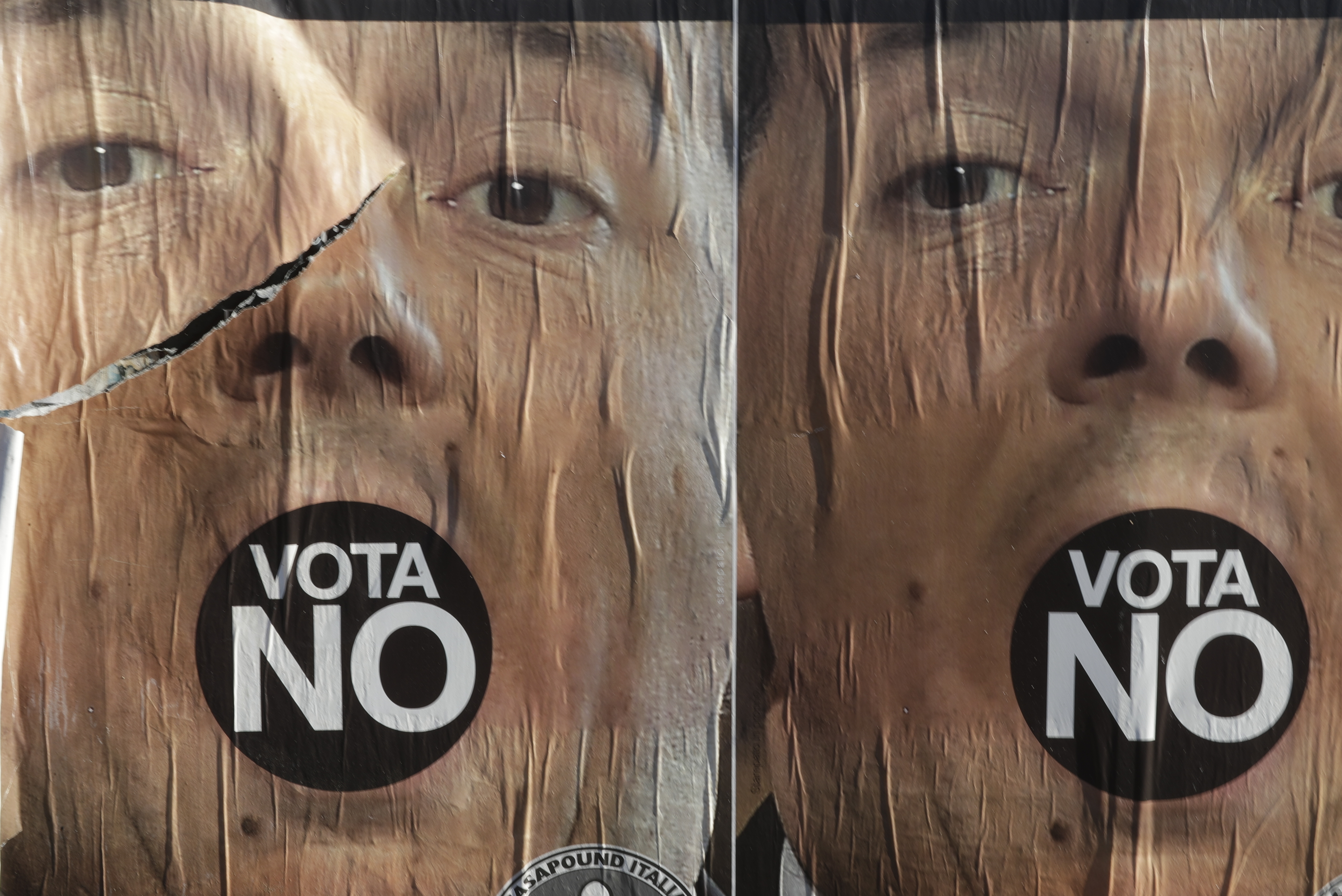

This time, the tremor rattled Italy. The country's dashing young prime minister, Matteo Renzi, has resigned after putting a change to the Constitution up for a referendum vote, and getting smacked down. With voter turnout at around 70 percent, 59 percent of the vote was against his referendum, which was intended to streamline government.

If Renzi is the big loser here, the country's populist parties are the big winners. With the left in disarray and the right allied to the Lega Nord party, the possibility of populists reaching power in Italy is looking more and more plausible with each passing day.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Meanwhile, the rejection of the referendum is bad news for the prospect of Italy's government actually getting anything meaningful done. The country has long been ungovernable, because it has two chambers with equal powers to bring down the government, and its electoral system creates coalitions of squabbling small parties, which means governments cannot push through ambitious legislation and cycle together easily. To give some perspective on Italy's governmental instability, Italy's new prime minister will be the fifth to have the job since Angela Merkel took office in Germany.

Italy remains the sick man of Europe, with its banking sector in tatters, high debt, and low growth. The fear is that the referendum result might unleash a chain reaction: a new banking crisis, leading to a new debt crisis for Italy, leading potentially to Italy being kicked out of the euro, or the European Union, or both. Thus far, though, the consensus seems to be "steady as she goes." Italy's president will try to appoint a new prime minister who can cobble a coalition out of Italy's squabbling parties and try to keep things moving.

The near-term consequences of Italy's referendum may look muted, but the long-term trend is impossible to ignore: European voters are unhappy. Britain had Brexit. Austria had two anti-establishment candidates, one from the left and one from the right, facing off for the presidency, kicking out the two main governing parties from the runoff for the first time in the country's postwar history. In France, on the right, the two establishment candidates have been crushed in this year's conservative primary, and on the left, incumbent President François Hollande bowed to political reality and will become the first president in the history of the Fifth Republic not to seek re-election. In Spain, the conservative government limps on without a majority. Poland already has a very right-wing government, and Hungary's Viktor Orban is proud to paint himself as that country's Donald Trump.

We know the voters are unhappy. And they have every right to be.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The euro has been an abysmal failure. You can't have a single currency for widely different economies, at least without a federal government. What's more, the European Central Bank's policies have been run largely for the benefit of the Eurozone's single most important member: Germany.

Then there's the European refugee crisis. You can say whatever you want about the necessity for richer countries to have a policy of compassion towards those less fortunate. It's quite another thing to welcome so many people that it might alter the continent's cultural profile forever. In Germany, it's possible that half of the under-40 population might consist of immigrants from outside Europe, a recipe for political disaster even in the most rosy-eyed projection. As the scholar Valerie Hudson noted in an important essay, Sweden is now poised to have the world's most skewed sex ratio for teenagers, which is a recipe for cultural dislocation. At least one of the Paris attackers came through the earliest waves of unvetted refugees.

To be concerned about this is not racism or even nativism. It might be misguided; it is certainly legitimate. And Europe's migrant policy paints the picture of an out-of-touch elite more concerned about making already economically stressed Europeans bear the cost of their own virtue signaling, rather than an elite that has its fellow citizens' best interests at heart.

But there is an even bigger problem at bottom for Europe's ruling class, and it is a crisis of legitimacy. Since the end of World War II, increasingly large sections of the European elite have pursued the dream of a federal Europe, a United States of Europe. That dream is well-meaning. Elites believe that accomplishing this dream would put an end to nationalism and prevent the sort of great European power wars that lit the world aflame in the 20th century. But another lesson of history they failed to learn is that governing elites with grand ideological designs and little capacity for self-questioning are among the world's most destructive phenomena.

Europe's federalist elites are not supported by their nations, and they know it. Their response to this knowledge, collectively, has been to essentially ignore it and do what they want anyway. Remember when, in 2005, voters in France and in the Netherlands rejected a planned "Constitution for Europe"? As a result, did elites rethink their massive project? No, instead they created something called the Treaty of Lisbon, which is essentially the same thing with only a few cosmetic changes, and pushed it through national parliaments anyway.

There's a cliché that says the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result every time. Many in the commentariat worry that Europe's populists aren't "sane" enough. And indeed, concern on that front is more than warranted. But populist success is always a result of elite failure, and by that definition, it is Europe's elites that are insane. They desperately need a dose of sanity, or else Europe's populist insurgency really risks spinning out of control.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?Feature Possibilities include to curry favor with Trump or to try to end financial losses

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military