How Kellyanne Conway became the greatest spin doctor in modern American history

How does she do it? Let's examine faux frankness, ice queening, cool girling, impatience signaling, and more of Conway's go-to strategies.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the few short months since she entered President Donald Trump's inner circle, Kellyanne Conway has mastered the art of message-muddying. As Trump's campaign manager, Conway frequently appeared on news programs to spin something objectionable Trump said. She was uncommonly good at it, but over time, a pattern emerged: There was (perhaps by design) no message consistency between Conway and Trump. He would frequently contradict her, and she would have to mop up the mess. At this, she is incredibly adept — perhaps the best ever.

But in her expanded role in Trump's White House, Conway has run into some difficulties. Her attempt to rebrand Press Secretary Sean Spicer's lies about crowd size at the inauguration as "alternative facts," for example, was (to put it gently) poorly received. Her public image has drifted from that of a reasonable woman doing an impossible job to something closer to SNL's portrayal of her as a latter-day Roxie Hart. And her ability to sow confusion, coupled with her sporadic assertions that she's not privy to Trump's thinking, has led some journalists to propose that networks stop interviewing her.

Is the Conway effect wearing thin?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Back during the presidential debates, I tried to analyze some of Trump's rhetorical moves in an effort to understand why they work. It's time to do the same for his silver-tongued subordinate: What exactly is Kellyanne Conway doing? And how is she doing it? And why isn't it working quite as well anymore? Here, a guide to Conway's go-to strategies for softening, massaging, and spinning:

Cool girling

If Trump says something offensive, she plays the Cool Girl, rolls her eyes at people's sensitivities, and remarks that it's no big deal.

Schoolmarming

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But when someone criticizes Trump, Conway takes schoolmarmish offense. She objected, for example, to former CIA Director John Brennan's word choice when he said Trump "ought to be ashamed of himself" for his behavior while addressing the CIA. Conway appeared scandalized. "And we have the outgoing CIA director making a statement like that, using that type of vocabulary," she said. That Brennan's "vocabulary" was rather tame is hardly the point. Neither was her concern for civility, given that Conway herself would — a mere two sentences later — accuse Brennan of sounding "like a partisan political hack."

Mothersplaining

If Trump says something outrageous, Conway becomes tender and maternal, asking, Madonna-like, that news outlets judge the president by "what's in his heart" rather than "what's come out of his mouth." "You have to listen to what the president-elect has said about that. Why don't you believe him? Why is everything taken at face value?" she pleads with CNN anchor Chris Cuomo, as if hers is the commonsense position.

Ice queening

While Conway is typically garrulous and warm, she will, on certain occasions, act angry or stern. This was her strategy when CNN's Jake Tapper asked whether Trump retweeting 16-year-old boys and insisting he'd won the popular vote he'd clearly lost was presidential behavior. "Well, he's the presidential-elect, so that's presidential behavior, yes," she said. "Just because the president does something doesn't make it presidential," Tapper replied. "Yes, I wasn't saying otherwise," she says. (Yes, she was — there is no other way to interpret her response.)

Sexisming

"I'm not one to run around screaming about sexism," Conway told The New Yorker — she's careful to signal that she's not one of those women. But sexism can be useful. If someone asks a pointed question, Conway will often look stung or hurt. To viewers, this signals that the rules of polite discourse have been violated: Journalists are boors! Kellyanne is a saint for dealing with them! She suggested Tim Kaine was sexist for interrupting Elaine Quijano, the moderator during the vice presidential debate. And when rumors hit that Trump was angry with Conway for her remarks about Mitt Romney, she denied the reports by saying, "It is all false. And sexist." (Why sexist? How?)

You're so mean!

On other occasions, Conway will simply accuse interviewers trying to get her to answer a question of badgering her (as she did Don Lemon here).

Downgrading confrontation to repartee

If someone tries to interrupt one of Conway's long digressions, she'll talk over them until the conversation hits an emotional (rather than a logical) snag. In this classic example of how hard it is to get Conway to give a yes or no answer, Cuomo (to his credit) ignores the optics of talking over a fragile-looking middle-aged woman. He insists that she address Trump's refusal to acknowledge the concern over the Russian hacks. "You just want to argue with me," Conway finally whines, almost flirtatiously, as if his concerns over the election being compromised are a pretext for a personal conflict he has with her.

That should have been the moment she lost, but it isn't: Cuomo responds to the implied injustice. "Not at all, I love you, Kellyanne," he says.

The defeat is apparent in his face as soon as he's said it.

Conway's twin messages seem to be: "Bring it on, I can take you" and "you're not playing fair." The deck is stacked against me and everyone watching knows it, she seems to say, but I'm ready to play anyway, because that's how right I am. It's an affect that makes her seem scrappy, put-upon, tolerant, even noble.

But Conway's gift for "subtracting from the viewer's understanding," as NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen calls it, involves more than optics and more than gender. It's speed, for one thing. She rarely pauses at the end of a sentence. It's digression. And it's range. She's able to package entire arguments — whole scripts — into short sentences. It's not just necessary but essential to slow down and examine some of her appearances to see just exactly what she's doing.

Here's how Conway handled George Stephanopoulos' question about the White House petition with more than 200,000 signatures asking to see Trump's tax returns.

I choose this example partly because Conway offered an uncharacteristically straight answer (which she would, rather more characteristically, retract the next day). It's useful because she followed that unadorned response with a dizzying series of justifications that pivoted seamlessly into a complaint that the Democrats aren't ratifying Trump's nominees quickly enough. It's a remarkable performance. And it offers a useful (if partial) guide to Conway's bag of tricks. We'll go through it in an attempt to diagnose each rhetorical move.

Here's her initial straight answer:

"The White House response is that he's not going to release his tax returns."

Impatience signaling

Conway's next sentence was this:

"We litigated this all through the election."

The implication here is that the press is unfairly bringing up a settled matter — again, the question was a petition that had just hit the number to provoke a White House response. Conway is good at looking a little exasperated when she does this, like it's merely politeness that keeps her from speaking her mind. She goes on:

Conflating victory with impunity

"People didn't care. They voted for him."

The buried logic: Trump won, so any issues that arose during his campaign are off the table.

Faux frankness

"And let me make this very clear."

This is far from unique, but she does it well.

Concept scrabble

"Most Americans are very focused on what their tax returns will look like while President Trump is in office, not what his look like."

Conway frequently takes the words from the question — tax returns, Trump, Americans — and recombines them. It gives the impression of straightforwardness. The question, you'll recall, was how Trump will respond to a petition signed by 200,000 Americans demanding that he release his tax returns. Conway takes those concepts — "the people," "tax return" — and reshuffles them in a way that a) denies the premise (the 200,000 Americans who signed that petition fall out of her framing — let me tell you what the people care about, she says), and b) removes Trump from the sentence as an agent called upon to respond.

Imply bad faith

"And, you know full well that Trump — "

Note how gently this implies that Stephanopoulos has in some unspecified way misled the public on the point to follow. I'll tolerate your unfairness, she seems to say, but not your dishonesty.

Lie

"President Trump and his family are complying with all the ethical rules, everything they need to do to step away from his businesses and be a full-time president."

By saying that Stephanopoulos knows "full well" that Trump has done something he has not done, Conway makes it rhetorically much harder for him to challenge her lie.

Agenda Mad Libs

"But on this matter of tax returns, people keep a — they want to keep litigating what happened in the campaign. People want to know that they're going to get tax relief and he has promised that. We just hope the Democratic Senate will support his tax relief package the way the Democratic Senate in 2001 did for President Bush, George. They passed tax relief for all Americans by June of that year. We hope the same happens here. President Trump has appointed 21 of his 21 Cabinet nominees and only two have been confirmed. It's really time for Democrats to step up and stop talking about bipartisanship and be bipartisan when it comes to passing that tax reform so that Americans' tax returns look better this year and confirming these nominees."

This is Conway at her most impressive. She steers a question about Trump's lack of transparency about his tax returns — which caused a record-breaking number of Americans to sign a White House petition — to a charge that Democrats need to pass tax reform. This is pundit Mad Libs. She's replaced the "What the People Want" blank — FOR DONALD TRUMP TO RELEASE HIS TAX RETURNS — with another — FOR THE DEMOCRATS TO PASS TAX RELIEF. And done so in a way that implies that she is the one speaking for the people. (Never mind the people, who presumably signed the petition hoping to speak for themselves.) The concealed argument — "I won't address what the people who signed that petition want, I will only talk about what Trump supporters want" — is too well-hidden to be offensive.

The walkback

Having looked at the minutiae, it's instructive to consider Conway's strategy at the macro level. The day after this interview aired with that uncharacteristically straightforward response — "The White House response is that he's not going to release his tax returns" — Conway annihilated its usefulness:

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"181375","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"264","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"600"}}]]

Note the move: She muddily contradicts what she said one day earlier while asserting that there is no contradiction: "answers are same." Now, perhaps her boss was angry that she committed him to a position. Perhaps she misspoke. The least charitable interpretation is that this was a bit of sabotage to make the press look bad by implying they misrepresented her — a few weeks ago, that would have worked. People don't tend to rewatch interviews looking for inconsistencies. They read headlines and conclude that the media lied.

In thinking about how to transcend the Conway effect, it's instructive to study the people who've effectively interviewed her. Seth Meyers turned out to be a master at it: Comedians have a lot of experience quickly analyzing and calling out behaviors and tricks in ways that scan as funny rather than aggressive. As Vox's Caroline Framke says, "Meyers' interview with Conway worked because he pointed out when she was deviating from the topic at hand."

But equally important is the fact that Meyers — rather than serve up questions for Conway to spin — was awfully good at packaging micro-arguments of his own:

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"181377","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"161","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"600"}}]](Screenshot/Vox)

Meyers took Conway's statement — meant to discredit a press report — and took its interpretation away from her. In his hands, her statement became the terrifying story of a president-elect who couldn't be bothered to read his own intelligence briefs, even when they were about him. And he did it by using a more complex version of Conway's multifactorial rhetoric.

Let's look at one more example — because Conway's appearance this weekend on Fox News Sunday is notable for its tactical incoherence. Conway did some of the usual things: She rattled off numbers to put distance between the question and her non-answer. She mothersplained Stephen Bannon's remark that the press should "keep its mouth shut" by claiming she knows the contents of his heart: "What my colleague Steve Bannon is saying is, why don't you talk last and listen to America more. Let me tell you something, I know what he meant."

But then she said something not just horrifying but — given her usual diplomacy — odd: She slipped in a suggestion that newspeople who spoke out against President Trump should be fired: "Not one network person has been let go. Not one silly political analyst and pundit who talked smack all day long about Donald Trump has been let go." She followed that with a striking image that was clearly supposed to inspire pity for Conway the martyr, bravely enduring the whips and arrows of press freedom. But it doesn't land; in fact, it's actually kind of gross: "We turn the other cheek. If you are part of team Trump, you walk around with these gaping, seeping wounds every single day, and that's fine. I believe in a full and fair press." But note the peculiar phrase she introduces: a "full and fair press." Now, that's not an expression. It's not clear how one "believes" in a concept one just invented. But it does seem a) calculated to sound like what we actually have, a free press, b) a noteworthy trial balloon, perhaps intended to see whether Conway can get away with slowly substituting that for the actual phrase in interviews, and c) packaged as a noble response to the terrible suffering Trump's team has endured as the victors in charge of the White House.

Here's the thing: You're-so-meaning and Ice-queening in this way doesn't work nearly so well when you're actually in power. Neither does portraying yourself as the fragile injured party. Conway's strategies and microarguments worked as long as she was the embattled underdog. Now she's not. And she's flailing.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

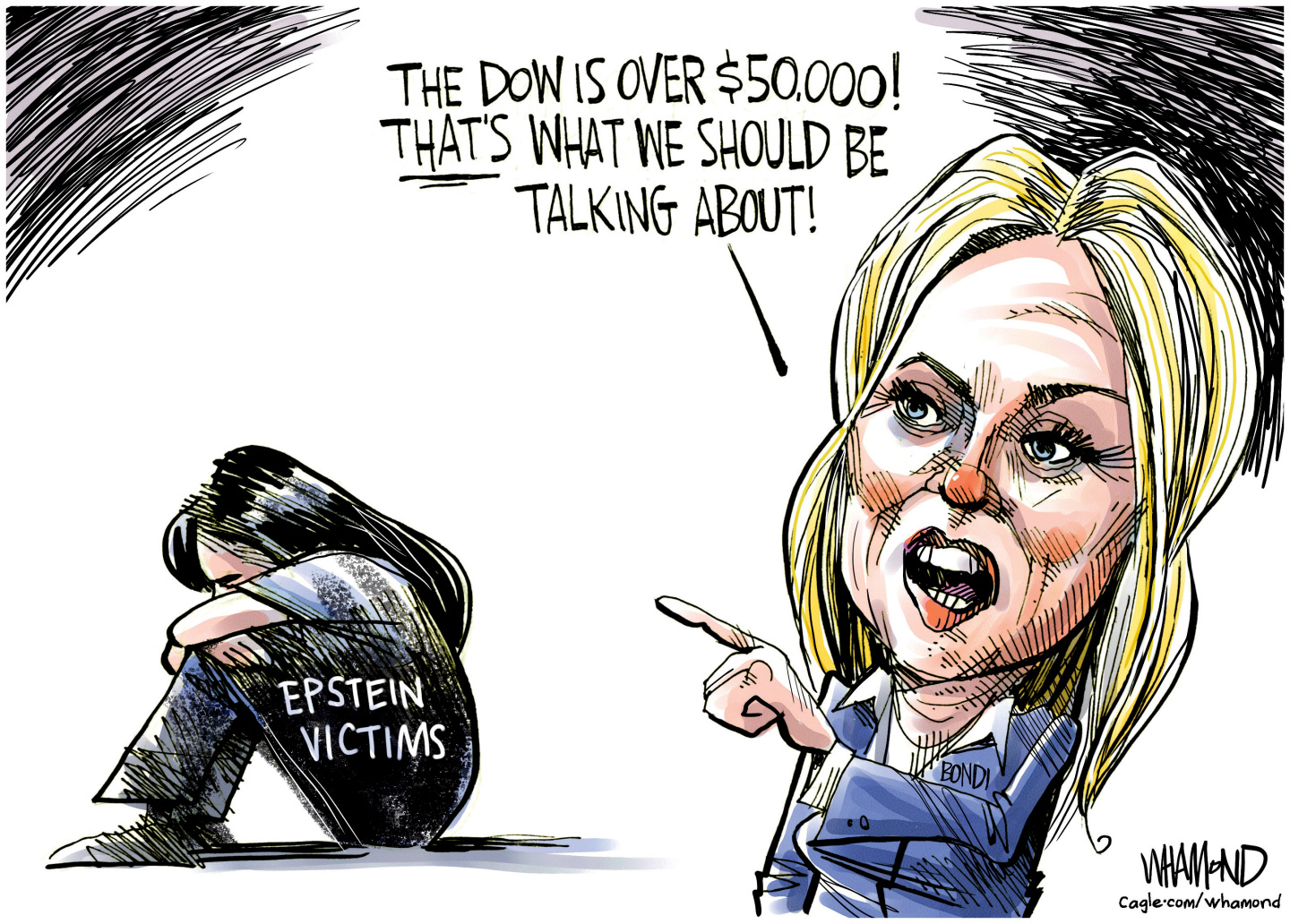

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred