Walking away from Louis C.K.

As a huge fan of his work, I naively hoped the rumors weren't true. But it's time to stop pretending.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the day his film I Love You, Daddy was supposed to premiere, Louis C.K. was instead featured in a New York Times story in which five women describe unwanted sexual encounters with the comedian and auteur. Old rumors have been sourced and corroborated, and it's starting to seem like there was an ugly conspiracy of silence around the guy whose comedic signature was his absolute, disarming, self-flagellating frankness.

I'm mourning these reports, as a fan, which is beyond embarrassing. It means admitting you were duped, and you're likely struggling between horror and denial. If you're a fan, you might — instead of registering the gravity of all this — notice your mind wandering. Even as it admires the women who came forward, it will also roam sloppily toward your love of the man's work. It might even alight, quite gingerly, on the question of comebacks. (Too soon! your brain will say, but Mel Gibson's back in Daddy's Home 2! Anything is possible!) But first there are other questions, like, what exactly has been lost? And how widely known was Louis C.K.'s alleged conduct? Is the comedy world as bad as Hollywood? Who knew what, and when did they know it?

If this feels like familiar territory, it's because we've been here before. Quite recently.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Exactly one month ago, Meryl Streep issued a statement responding to multiple allegations of sexual assault against Harvey Weinstein by challenging the idea that his conduct was an open secret. "Not everyone" knew, she said. This inspired a wave of "truthers" to speculate about how much these peers of Weinstein's knew and why they denied knowing it.

This question of who knew more than misses the point. One of the obvious things about sexual harassment is that people don't know about it. Sure, they might hear rumors. They might suspect. But people guilty of sexual misconduct tend to excel at victimizing people privately while charming the rest publicly; Weinstein was likely careful to keep his conduct secret from Streep, a powerful player in the business he wouldn't be dumb enough to victimize.

But it's true that the position of not knowing is the one in which most of us live. Our relation to stories of sexual assault that aren't our own necessarily makes us agnostic outsiders, whether they concern celebrities or neighbors or coworkers. This is our privilege. We get to live without the knowledge that victims carry with them every day. This is the loophole, the "if true" with which so many members of the GOP peppered their responses to the allegations of sexual misconduct against Alabama GOP Senate candidate Roy Moore.

I've been thinking about this a lot — this place we, the outsiders, the fans, duck into, hoping our idols will hold. Louis C.K. has mattered to me. Forget comedy; he's one of the creators I've most admired in my life, even as I've watched in concerned perplexity as his often excellent, thoughtful work took stranger and more disturbing turns. For a while, I've suspected the rumors about Louis C.K. might be true, but there were no accusers (yet) and there was just enough smoke to hope that someone had garbled the story. I was operating from a place of spiraling optimism caught mid-dwindle. I've even tried to explain some of the more disturbing content away, to fold it into an artistic project that absolved Louis C.K. from the predatory material he himself wrote.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It all seems to have been a lot simpler than I was making it: Some people get off on victimizing folks and getting away with it. What better way to multiply that frisson than by making your show (or film) about the stuff you know you've done?

Even last month, as I was writing a pointed examination of how perniciously our culture enables us to "not know" about sexual assault no matter how the charges are made or by whom, I — a feminist, a writer, someone who thinks a lot about the obstacles female artists face — clung to my ability to not know about the allegations against Louis C.K. "IF TRUE," I said to myself, fingers crossed tight.

That wishful thinking is over. Louis C.K.'s alleged misconduct is corroborated, and there will likely be more revelations. I'm reeling — from the colossal disappointment in someone whose artistic vision I blindly trusted, and from a loss so much greater that it's hard to take its full measure. I care a lot about people and the harm that's come to them. But as a critic, I also care about art. And the biggest, most horrifying pattern that's emerged as allegation after allegation comes out, in industry after industry, is that the victims leave the business. "Ms. Schachner accepted his apology and told him she forgave him," the New York Times story about Louis C.K. says. "But the original interaction left her deeply dispirited, she said, and was one of the things that discouraged her from pursuing comedy." She's gone. "I decided if this is what being an actress is like, I don't want it," said Sophie Dix of her encounter with Harvey Weinstein. She's gone. "One of the most striking things about all these pieces is how many women left the business, after discovering this was how it worked," wrote Emily Nussbaum.

That colossal loss, that talent drain, that tale of needless, ongoing attrition, is a national tragedy, the dimensions of which we will never know. I'm heartbroken about Louis C.K.; I admit that, even though I saw the heartbreak coming. I thought his work was honest. I thought it made the world better. It's useful to realize that he — along with all these other small and grubby souls — may instead be responsible for an unfathomable diminution of what American art and comedy could have been. There's no knowing how many people have been sacrificed — along with their great and gripping work — to the cause of someone else's genitals.

There's a tendency, when revelations like these come out, to mourn the loss of that particular artist's work (or worry that the person in question's life will be "ruined"). We mustn't forget the artistic carnage left in their wake.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

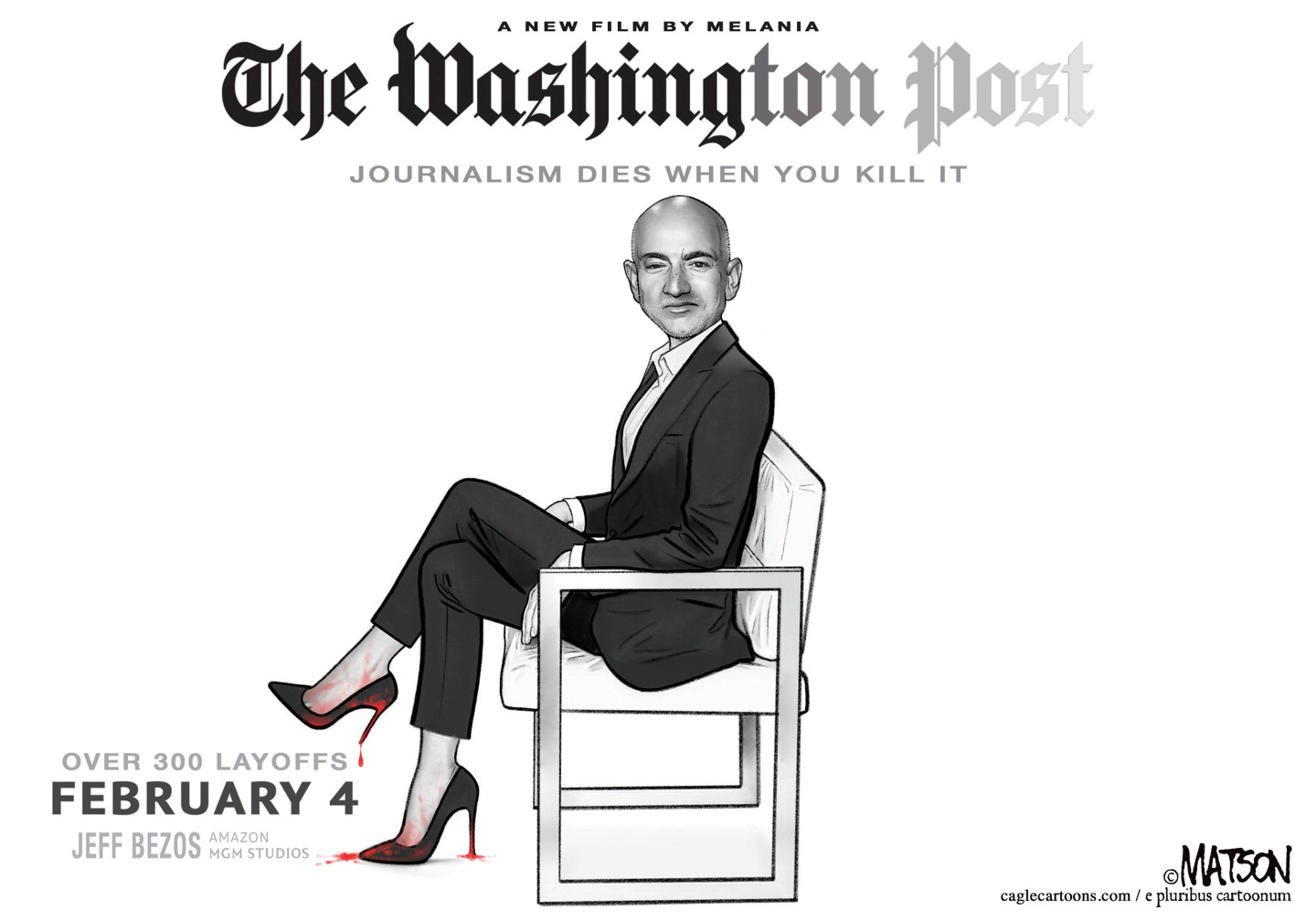

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

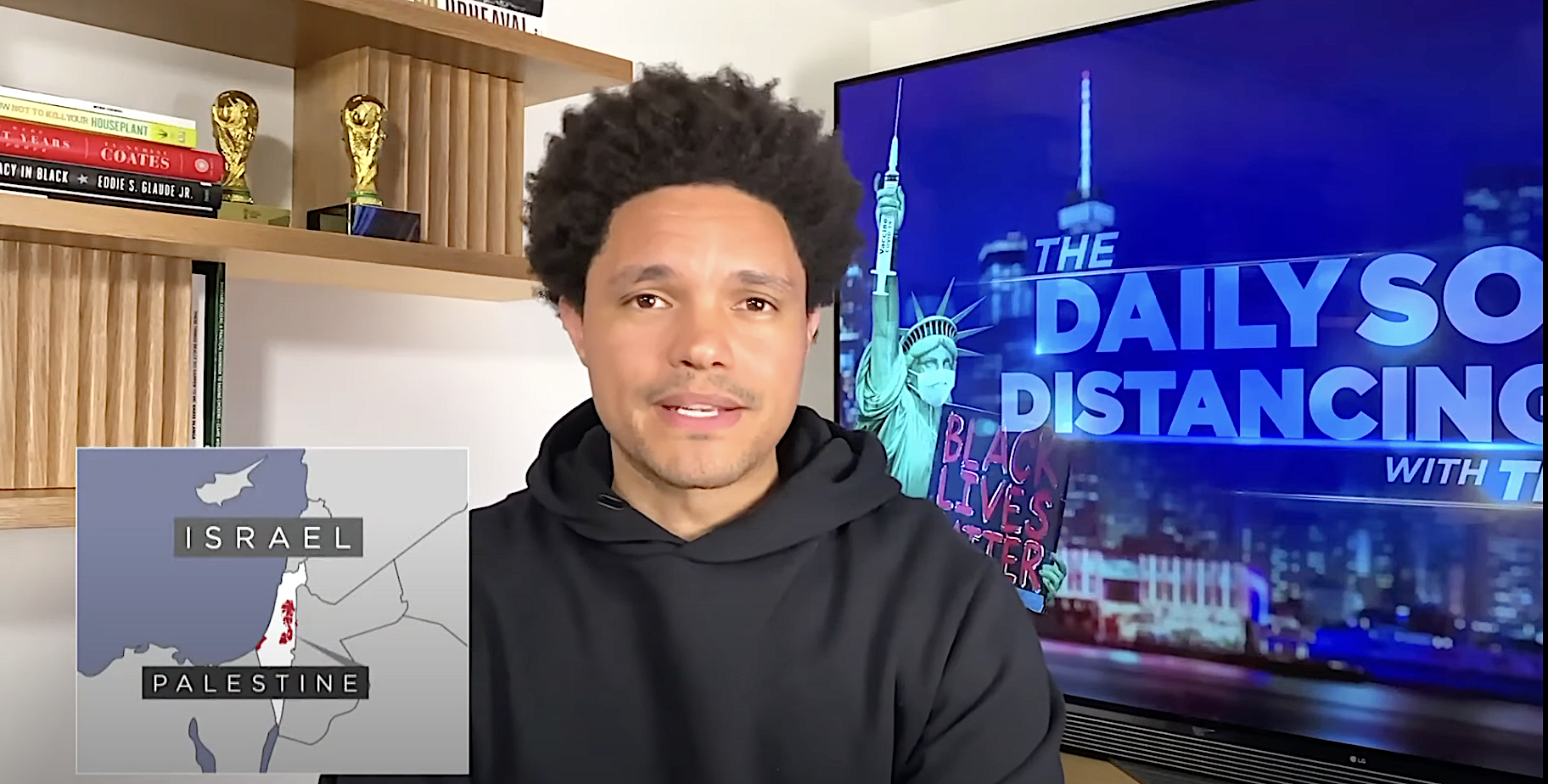

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white people

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white peopleSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar pains

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar painsSpeed Read