'No' is not enough

On our reductive understanding of female desire

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Men who are constantly trying to move things forward are exhausting in a way I find hard to articulate," a friend once wrote to me. "Like you never get to fall in love on your own." She wasn't referring to the #MeToo movement, or the gruesomely described date between "Grace" and Aziz Ansari, but her words have stuck with me, because she put her finger on one of the many costs our sexual mores impose on women: Desire.

#MeToo isn't anyone's first hashtag rodeo. Well, I suppose actually it must be somebody's, since new people continue, frighteningly, to be born, to log online, and to share their lives there. But that aside, like #YesAllWomen before it, #MeToo is borne of a collective optimism that male violence against women is a problem stemming from male ignorance, to be solved through a collective baring of scars. And like #YesAllWomen, or for that matter, SlutWalk or Take Back the Night or any number of mass initiatives, #MeToo has also produced its own women's counter-reaction, amply represented by writers like Bari Weiss and Daphne Merkin (in The New York Times), Caitlin Flanagan (in The Atlantic), and (eventually, and already somewhat notoriously) Katie Roiphe in Harper's.

For Weiss, Merkin, and Flanagan, the looming danger of #MeToo is that it emphasizes a woman's vulnerability over her agency, and importantly, her sexual freedom. And being free means accepting consequences, such as a bad date in which a man's sexual behavior crosses a line. The freedom women can exercise in these situations is saying no, and "[taking] the risk that comes with it," as Merkin puts it. "If [a date] pressures you to do something you don't want to do," writes Weiss, "use a four-letter word, stand up on your two legs, and walk out his door." And Flanagan looks toward the women's magazines of her youth, which emphasized that women always had the right to decline an unwanted advance.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what kind of freedom is saying "no"? In the already much-dissected account of the date between the anonymous "Grace" and Aziz Ansari, "Grace" does indeed say no, both verbally and not. But her options are either to leave or take her lumps — that she might have wanted to have sex with Ansari, but in a way that incorporated her own desires or indeed even left room for her to speak, isn't on the table. Female sexual agency exists only in deciding what any given woman is willing to submit to, not what she wants.

Why don't these women know they are prey? This is the irritated question that runs through the reactions of Weiss, Merkin, Flanagan. The simple answer is that these women aren't prey, that they refuse this designation. A rabbit isn't exercising any kind of freedom in merely saying, "Not today, Mr. Wolf," or selecting between a wolf and a rather tame dog. And if the relationship between men and women really were that of a rabbit and carnivore, women could really be excused in using just about any method to level the playing field.

But it's not, because women, much like their male counterparts, feel desire, even unwise desires or desires that seem to overthrow reason; and I don't think that desire is the desire to be consumed and digested (at least for most of them — it takes all kinds). Women fall in love, experience sexual humiliation and rejection, and, contra Andrew Sullivan, the ambient sexual itch we call "horniness" is something they feel too. The problem is that you can't say yes in a world in which your yes is presumed until someone gets a no, just as you can't say no and be understood if no is the only word you're permitted. You can't express desire to a partner who can understand your desire only in terms of acquiescence.

One casualty, not the most important but assuredly real, of men's predation is women's desire. In her book Intercourse, Andrea Dworkin — an author and a book both not known for a rosy understanding of heterosexual relations — writes that "women have a vision of love that includes men as human too; and women want the human in men," that they hold on to "visions of a humane sensuality based in equality." She immediately goes on to deflate these dreams, pointing out that they do not "amount to much in real life with real men."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Still, I remember the shock of reading them for the first time; in the middle of such a fierce and upsetting polemic, the presence of this unfilled and graceful hope: that women can not only be regarded by men as human beings, but that men can act as human beings too. Beyond the rabbit and the wolf, there's a whole world. Isn't it time we went there?

B.D. McClay is a senior editor at the Hedgehog Review.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

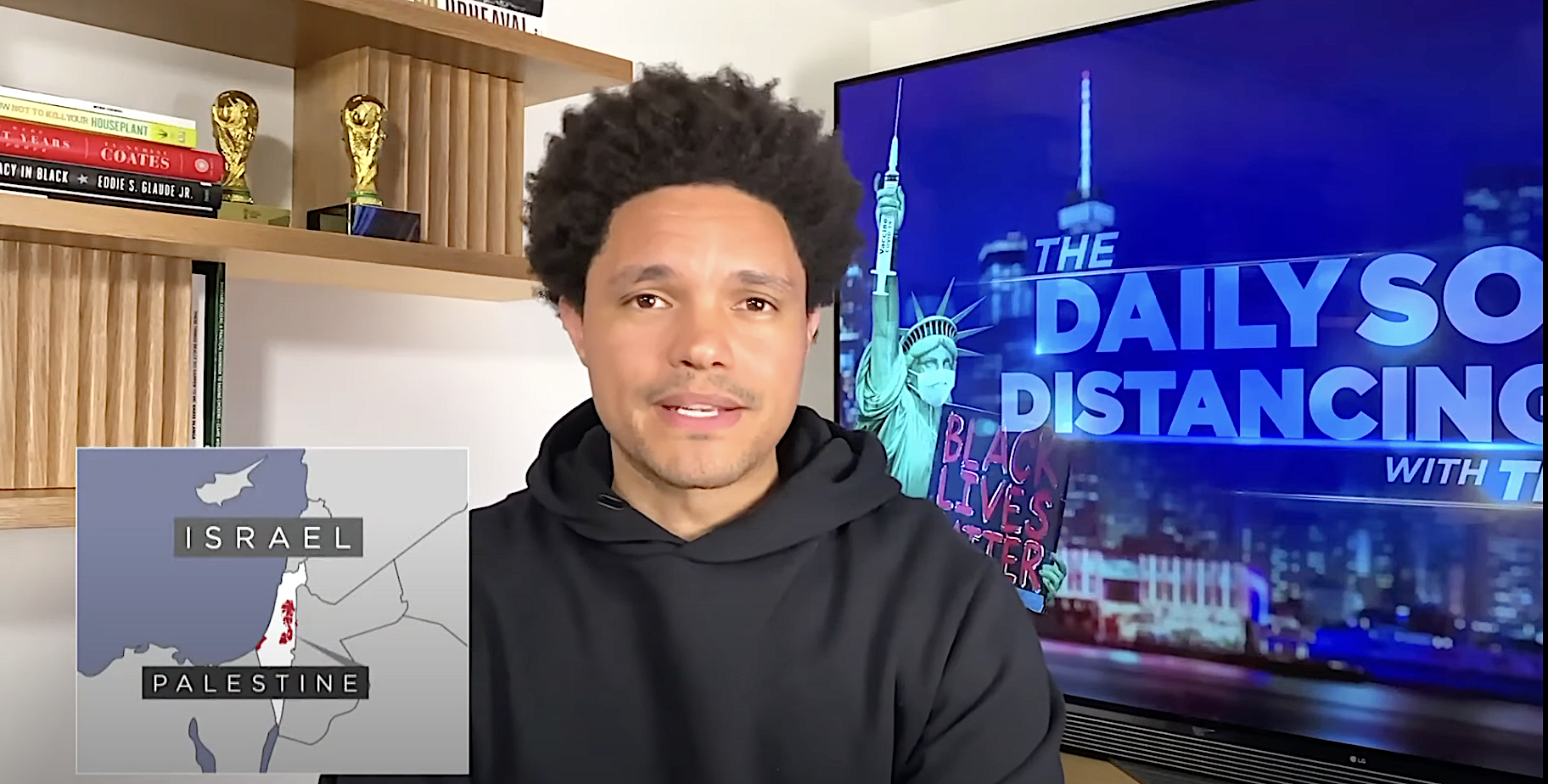

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white people

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white peopleSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar pains

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar painsSpeed Read