Trump's once-in-a-generation chance to remake the Fed

The Fed has been understaffed for years, giving Trump an opportunity to mold America's central banking system in his image

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Trump's nominations to the Federal Reserve Board are making headlines, and for good reason. Both Stephen Moore and Herman Cain are viewed as under-qualified, and their previous stances on monetary policy reveal a willingness to say whatever's politically expedient for Republicans at that particular moment.

But the growing controversy over these two nominations emphasizes a much deeper problem: In recent years, the Fed has been increasingly understaffed. This means that Trump may have the opportunity to completely remake the Fed in his image.

The Fed is run by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). It's made up of 12 voting members. Five of those seats are set aside for the presidents of the Fed's 12 regional branches, and they automatically rotate in and out. But the other seven seats — collectively known as the Board of Governors — are nominated by the U.S. president and confirmed by the Senate.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It matters who sits on the FOMC. The Fed sets short-term interest rates throughout the economy: Lower rates tend to promote job and wage growth while allowing more possible inflation, and higher interest rates tend to prevent inflation at the cost of squashing jobs and wages. It's a precarious balancing act that implicates everything from inequality to Americans' livelihoods to basic economic and racial justice.

These officials also decide how ambitious and experimental the Fed will get with unconventional monetary policy in times of crisis. In addition, the central bank has a lot of regulatory obligations overseeing banks and the financial sector. The seven members of the Board of Governors all oversee the various Fed committees that perform those functions.

You'd think filling those positions would be as big a deal in U.S. politics as nominations to the Supreme Court — and that failures to keep the Board of Governors fully staffed would be as big a headline-grabbing scandal as the year-long vacancy that followed the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. But by all accounts, most U.S. politicians simply don't care about the Fed all that much.

Of the seven seats on the Board of Governors, only five are currently filled. If Moore and Cain are confirmed by the Senate, that will make six and seven. But while any level of under-staffing is a problem, five is generally considered the magic number below which real problems start. With fewer than five people on the Board of Governors, the Fed faces real practical problems in carrying out its myriad regulatory duties. And emergency actions become harder to agree upon.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Moreover, the five seats filled by Fed branch presidents are always stocked. An FOMC with two empty Governor seats is split evenly between the two batches of officials. An FOMC with three or more absent governors actually gives the voting majority to the regional presidents. This can be a problem, because these officials are much more insulated from the democratic process, and they tend to be culturally and ideologically bound up with the interests of business owners and the banking industry — which is to say, they are much more likely to prioritize low inflation over low unemployment.

At any rate, since the start of former President Obama's administration, the Fed has been at five for unusually long stretches, and has actually started falling below that number. Under Trump, the problem has gotten significantly worse.

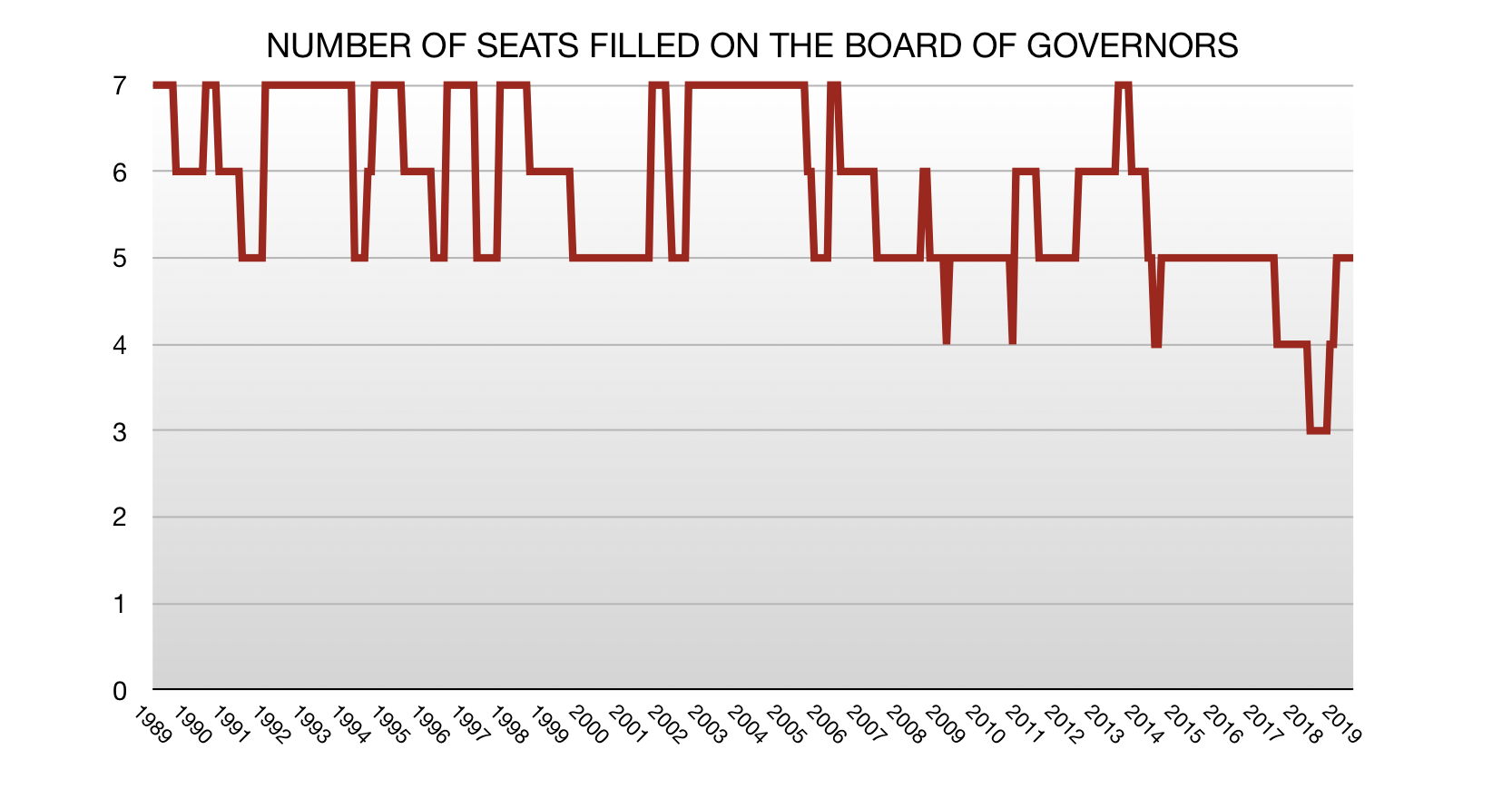

As you can see, the Fed has had five Governors every so often for decades. Though the Governors are ostensibly confirmed for fixed 14-year terms, they tend to resign more frequently for all sorts of reasons. Historically, though, whenever the number has fallen to five, it has quickly bounced back.

That changed in the Obama era, and there's plenty of blame to go around. GOP congressional obstruction under Obama was legendary. Senate Republicans refused to take up at least two of Obama's nominees: Peter Diamond in 2010, and Allan Landon in 2015.

The general assumption is that liberals are more dovish on monetary policy, and conservatives more hawkish. But as Matthew Yglesias noted at Vox, Obama's nominees weren't particularly dovish, and the Republican objections rarely lined up with any coherent ideological view of interest rates. Meanwhile, Obama himself never showed any great urgency in filling the seats — apparently because he believed monetary policy had been rendered impotent once the Fed dropped its interest rate target to zero in the aftermath of the Great Recession. That's a debatable idea, but even if it were true, it would still have behooved Obama to put his stamp on the Fed, both to ensure it was more dovish and progressive when it finally did raise rates, and to avoid leaving it open to right-wing nominees should he be succeeded by a Republican in the White House.

The periods during which the Board of Governors had fewer than five filled seats were blessedly short under Obama: a few days in 2009 and 2010, and roughly three months in 2014.

Then came the Trump administration, and the number has been stuck at five. But it was below five for more than a year, dropping down to four and even three.

Trump has proven supremely lackadaisical about filling roles across the executive branch, and the Fed appears to be no exception. That said, he's also had at least two nominees scuttled by the Senate. Marvin Goodfriend came off as ill-prepared when he got grilled by Democrats on the Banking Committee. And Nellie Liang was actually done-in by bank lobby opposition over fears she was not sufficiently supportive of deregulation.

A more subtle thread running through all this is that Trump (like many of his peers) doesn't appear to have a particularly fixed ideology about monetary policy. And to the extent he's developing one, it's actually in tension with the general inflation-hawkery we usually see from Republicans. Three of the five filled seats on the Board of Governors are Trump nominees, and one of the remaining two — Jerome Powell — owes his elevation to Fed chair to Trump. Still, this Fed has actually shown itself to be quite moderate. Trump reportedly blames the sluggish economy on the Fed's slow-but-steady interest rates increases, and views nominating Powell as a major mistake on his part. Moore and Cain seem like an effort to course correct.

The irony is that if Moore and Cain fill out the remaining seats, what we'll get is not necessarily a more hawkish central bank. We'll get a Board of Governors staffed by moderates and two Trump apparatchiks. How will such a Fed behave once Trump leaves office? We'll have to wait and see.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.