Is the recovery stalling out?

Troubling indicators buried in the jobs report

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Friday's jobs report showed a paltry 75,000 increase in American employment for May. Revisions to the jobs data for March and April knocked another 75,000 jobs off their cumulative gains as well. The country's low unemployment rate of 3.6 percent continues to stick. But at this point, it might be worth asking if the recovery is beginning to stall.

Interestingly enough, the disappointing number of added jobs isn't even the main reason to worry. It's a few other indicators, buried in the jobs data, whose trends are raising the red flags.

First up is wage growth.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When jobs are scarce, but the supply of unemployed people looking for work is plentiful, employers have all the leverage. People will take whatever employment is on offer, no matter how low the pay or how demeaning the conditions. But a low unemployment rate suggests the supply of jobs is beginning to pull even with — or at least close in on — the supply of potential workers. As that happens, those workers gain more leverage to demand more pay and better conditions.

While the unemployment rate is falling at a slower pace than before, it's still falling. Thus, you'd expect wage growth to keep accelerating accordingly. And it did — up until about six months ago. Since then, the rate of wage growth has either flatlined or declined.

We've generally gotten wage growth rates between 3.5 percent and 4 percent in the last few business cycle peaks. So this isn't a disaster. But up until the start of 2019, wage growth was accelerating quite rapidly. The sudden stall — especially when we still haven't broken above 3.5 percent yet — is disconcerting.

Next up, why the disconnect between unemployment and wage growth in the first place?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To count as unemployed in government statistics, you need to have looked for work in the last month. There's nothing wrong with that cutoff — it would make zero sense to count everyone in the country who isn't working as "unemployed." But there's always the attendant risk that the unemployment rate will undercount the true number of potential workers out there.

It looks like that's what's happening: The labor force participation rate, which includes both everyone with a job and everyone searching in the last month, plunged after the Great Recession and never recovered. More tellingly, the portion of people getting jobs each month who didn't look for work in the previous month — and thus wouldn't have been captured by the unemployment statistics at all before they got hired — is bigger than its been in decades. We should look at other metrics besides the unemployment rate to get a sense of the true health of the labor market. A particularly useful one is the prime age employment rate — the portion of all Americans age 25-to-54 who have jobs.

Because this measure excludes the particularly young and the particularly old, it's less likely to get thrown off by purely demographic changes. Recent research also suggests the prime age employment rate now does a better job predicting the rate of wage growth than the headline unemployment rate.

I bring all this up because the prime age employment rate has also stopped rising over the last six months or so.

Maybe it's just a blip, and it will pick up again. But this metric has been steadily rising since 2012, and now it's flatlined for a long enough period to be noticeable. On top of that, the prime age employment rate is still a little below where it was at the peak of the 2007 business cycle, and it's still well below where it was at the top of the late 1990s boom.

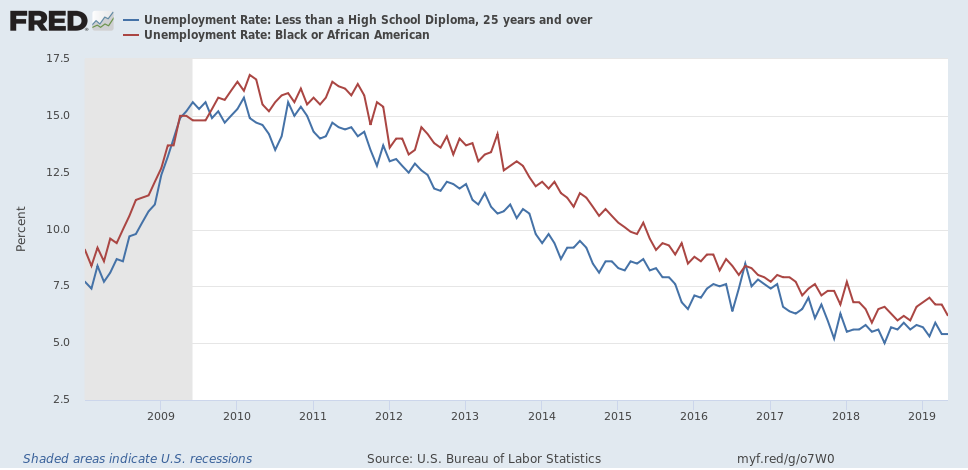

Finally, let's talk about the unemployment rate again — specifically, the unemployment rates for black Americans and for Americans with less than a high school education.

Some people in the U.S. labor force have a lot more innate privileges and social advantages than others. The unemployment rates for white workers and college educated workers, for example, are consistently lower than unemployment for less privileged groups, and lower than unemployment for the nation as a whole. Conversely, no matter how low white unemployment gets, the black unemployment rate tends to be nearly double the rate for whites — currently 6.2 percent to whites' 3.3 percent. The unemployment rate for workers without a high school degree is consistently almost three times as high as unemployment for people with college educations — currently 5.4 percent to college grads' 2 percent. These Americans are the last to be hired in a boom and the first to be fired in a bust.

One thing this means is it's incredibly important that we not only sustain the current low national unemployment rate, but get it down even lower. We have loads of evidence that these all-too-rare periods of low unemployment disproportionately benefit poor workers, black workers, and less educated workers.

But it also means that black and less-educated workers are the canaries in the coal mine. If there's weakness in the economy, it tends to hit them first. And sure enough, in the last six months or so, the unemployment rates for these two groups stopped falling.

What's the takeaway from all this?

We're certainly not in four-alarm fire territory. But while the recovery from the Great Recession has been steady, it's never been strong. (That's why it's still incomplete after 10 years.) Despite every incremental improvement the economy has gained over time, it's always been hanging on by its fingernails.

The Federal Reserve is discussing cutting interest rates again; it should go ahead and do it. Meanwhile, we could use more fiscal stimulus. The GOP tax cut was a dud, but the Republicans have quietly increased government spending in recent budgets. At a minimum, that should continue. Even better would be a major long-term investment, like a big infrastructure plan or Sen. Elizabeth Warren's (D-Mass.) new economic patriotism proposal.

Let's not be lulled into complacency by the headline unemployment number. The recovery needs some shoring up.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military