Is an aging population actually bad for the economy?

It's more complicated than most people seem to think

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Birth rates have been falling for decades, not only in America but around the world, which now means the amount of older people is growing in proportion to many nations' working-age populations. Pretty much everyone on both sides of the aisle assumes that's bad for national economies. Conservatives rely on this assumption to argue for higher birth rates, liberals rely on it to argue for more immigration. I've written articles based on this assumption.

But what if the assumption is wrong?

It turns out the evidence that aging populations harm economic growth is far from conclusive.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There are several mechanisms by which mainstream thinking assumes that harm occurs. For one thing, if a smaller share of your population is working, the remaining workers have to labor even harder and be even more productive to keep everyone's living standards on the rise. More old people also presumably means more savings available relative to investment opportunities, which supposedly drives down interest rates and makes investment less attractive. Finally, the wealth produced by the working population has to be spread out and shared at a greater rate, which can presumably cause political strife.

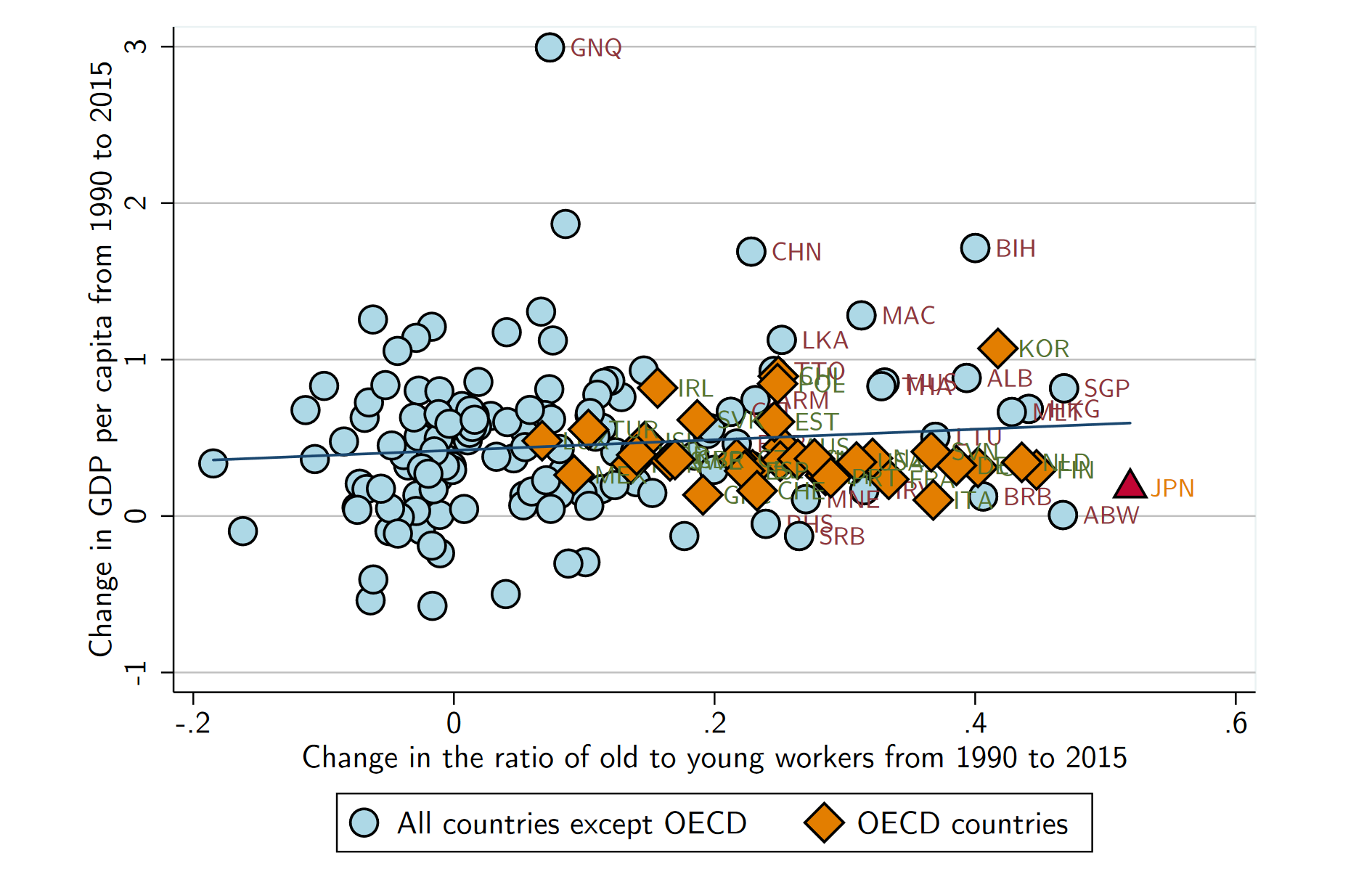

One thing all of these stories should end with is a slowdown in economic growth per person. In 2017, the economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo looked at how rapidly GDP per capita grew between 1995 and 2015 in a whole bunch of countries (the vertical axis below) and compared it to how much the ratio of old people to working-age people changed (the horizontal axis) over the same period. Contrary to the prevalent assumption, they found basically no relationship at all.

Another recent study out of Australia looked at rates of population growth across countries. The nations with slower population growth — up to and including negative population growth — actually saw faster growth for both GDP per capita and worker productivity.

The mainstream assumption seems to be largely driven by the example of Japan, which really has seen a massive drop in its fertility rate, a massive rise in its share of elderly, and a brutally persistent stagnation in its economy. But Acemoglu and Restrepo actually marked Japan with a red triangle in the graph above. And as you can see, Japan is at the extreme end of the overall global pattern.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Within American specifically, there's also a historical problem with this story.

It turns out that our dependency ratio — the number of non-working age persons relative to working age persons — was higher in the 1950s and 1960s than it is today. The reason was children; we had way more of them running around back then, and they more than made up for the smaller proportion of old people.

Now, there may well be sociological reasons why a high ratio of children to working Americans is different from (or preferable to) a high ratio of elderly. But from an economic and political standpoint, the distinction shouldn't matter much. Economically, you still face the challenge of making workers productive enough to cover the living standards of all the nonworkers. Politically, you still have to redistribute that wealth from the workers to the nonworkers. Since the mid-century boasted some of America's most dramatic economic growth in the last hundred years — abundant employment, rapidly rising wages, and robust productivity growth — this is another blow to the theory that a large nonworking populace is an albatross around the economy's neck.

What about the contrary evidence?

Two recent studies here in the U.S., and another one in Europe, did find a statistical correlation between an older population and productivity slowdowns. In particular, they focused on how a population with more old people overall is also a population with more old people among those who are still working age. The theory, which seems intuitive enough, is that older workers are slower to adapt to changing circumstances, technologies, and business models, and are thus less productive.

But again, we should be cautious. How well workers adapt to changes in the economy is a two-way street. It's partially dependent on workers' characteristics, yes, but it also depends on how much effort and money employers put into helping their workers adapt. Recent decades have brought major shifts in bargaining power, away from workers and towards employers, giving the latter way more freedom to drop their end of the bargain.

The U.S. studies also relied partially on correlations between state-level rises in the elderly population share and slowdowns in state-level growth. But one of the most dramatic recent changes in our domestic economy is the geographic reshuffling of economic opportunity into specific places. If you assume young people are more likely than old people to chase economic opportunity, then what these studies could be inadvertently picking up is the changing economy's effect on demographics, rather than demographics' effect on the economy.

So let's say it is in fact incorrect that an aging population is an economic drag. What could we have gotten wrong?

Acemoglu and Restrepo collected a fair amount of circumstantial evidence that countries with more old people actually put more effort and resources into improving economic productivity with automation and technology. In other words, countries that go through these demographic shifts seem to actually be pretty good at adapting their economies accordingly — though the correlation between aging and technology adoption appears to be stronger in the more advanced economies. It's certainly possible a shift could be so profound that it overwhelms a nation's ability to cope, but the global evidence suggests few countries have actually hit that threshold.

The theory that more old people means more saving relative to investment opportunities also makes a hash of how the economy really works. Because both government spending and bank loans are ways to create new money supplies, there is no "limited supply" of financial capital to drive investment. How many elderly savers there are simply doesn't matter. Furthermore, the amount of investment opportunities in the economy is driven by the amount of aggregate demand — and old people and children, even if they aren't working, still participate in consumption. Put it all together, and if your economy is stagnating due to chronically low interest rates, it doesn't mean you have too many old people. It means you haven't pushed enough Keynesian-style stimulus through your economy.

At any rate, while there is evidence out there that older populations are a problem for economic growth, it's hardly dispositive. There's plenty of reason to doubt it, and plenty of evidence in the opposite direction.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.