America is a foreign policy control freak

The march to war with Iran reveals America's obsessive need to intervene

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Whether it was undertaken by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen or by Iran itself, the bombing of an oil refinery in Saudi Arabia is obviously an act of war.

But was it an act of war against the United States? Just as obviously, it was not. The crippled refinery is 6,000 miles from the U.S. It isn't owned or run by Americans. The U.S. doesn't have a mutual defense alliance with Saudi Arabia. The relationship between our countries is one of sponsor and client. We sell the Saudis more weapons than any other country in the world, presumably so they can defend themselves. The U.S. isn't even as dependent on Saudi oil as it used to be.

Yet here we are, contemplating war with Iran (yes, launching missiles at a sovereign nation is an act of war, even when we do it) in response to Iran's probable act of war against Saudi Arabia. That remarkable fact gives us a perfect occasion to reflect on the confused mess that American foreign policy has become.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The first thing to notice about the way we conduct ourselves in the world is that diplomacy now counts for next to nothing. We issue blunt orders and threats to bring about “regime change” that provoke a prideful refusal to compromise on the part of our adversaries. We impose economic sanctions that inflict considerable pain while doing nothing to improve relations with the U.S. or the lives of those living under repressive governments. (Sanctions have been in place against Cuba for over 60 years.) We set preconditions for talks that we know ahead of time our adversaries will reject, all so that we can pin the blame on them for whatever follows as relations worsen. All of which produces a glide path toward the use of military force.

When it comes to the use of force, presidents are now free to do whatever they deem necessary without having to ask Congress for authorization, let alone a formal declaration of war as outlined in the Constitution. This allows the commander-in-chief to keep the threat of war permanently on the table in his dealings with recalcitrant nations while also relieving feckless members of Congress of responsibility for the consequences of our actions around the world. That might be good for politicians, but it's terrible for the United States.

All of this follows from an almost clinical predisposition toward control-freak tendencies. Arming the Saudis to the teeth and allowing them to use those weapons to protect themselves isn't good enough. We'd rather take action ourselves to maximize the chance of controlling the outcome — because controlling events (or at least attempting to do so) across ever-wider swaths of the globe is now treated as a necessary condition of protecting American national interests.

This hasn't always been true. From 1980 to 1988, Iran and Iraq fought a bloody war that left hundreds of thousands dead, and the U.S. remained mostly on the sidelines, reasonably concluding that the outcome of the conflict was of marginal importance to American interests. But today, we're willing to risk, threaten, and wage war all over the world — in the Middle East (Iran, Iraq, Syria), in Latin America (Venezuela), in South Asia (Afghanistan), in East Asia (North Korea, Taiwan), in Africa (Libya, Somalia, Niger). Having defined our interests in terms of imposing order and control everywhere, we think we have dogs in just about every conflict on the planet.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And that points to a final aspect of our muddled thinking foreign policy: its utter lack of strategic vision. What is the U.S. trying to accomplish in the world? What are our priorities? What regions matter most of all to us, and which less? Where are will willing to risk war, and where not? Those questions — which presume the existence of limits to American power — never seem to get raised. Our actions, meanwhile, imply that we would rather assume, absurdly, that American power has no limits — that there is no need to prioritize, to deem some countries and regions as more important than others. We'd rather consider ourselves the world's self-appointed policeman, judge, jury, and executioner of international justice. We're Superman, or would like to think so.

But of course we aren't Superman. No one put us in charge of the world. Our power and resources aren't unlimited. We need to set priorities, which presumes an ability and willingness to think soberly about when it's necessary to threaten the use of force to defend the country and its interests, and when it isn't. In terms of defending the American homeland, we've never been safer. But projecting our power to multiple far-flung regions of the world is terribly costly and brings benefits that are exceedingly difficult to define.

Maybe it's time we stop bluffing and start picking our fights more wisely. The first step should be recognizing that the conflict heating up between Saudi Arabia and Iran isn't our business. Our plate is already fuller than it should be. It's long past time for America to say no to starting yet another war.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTU

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTUIN THE SPOTLIGHT How does the party out of power plan to mark the president’s first State of the Union speech of his second term? It’s still figuring that out.

-

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanches

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanchesThe Explainer Several major ones have recently occurred

-

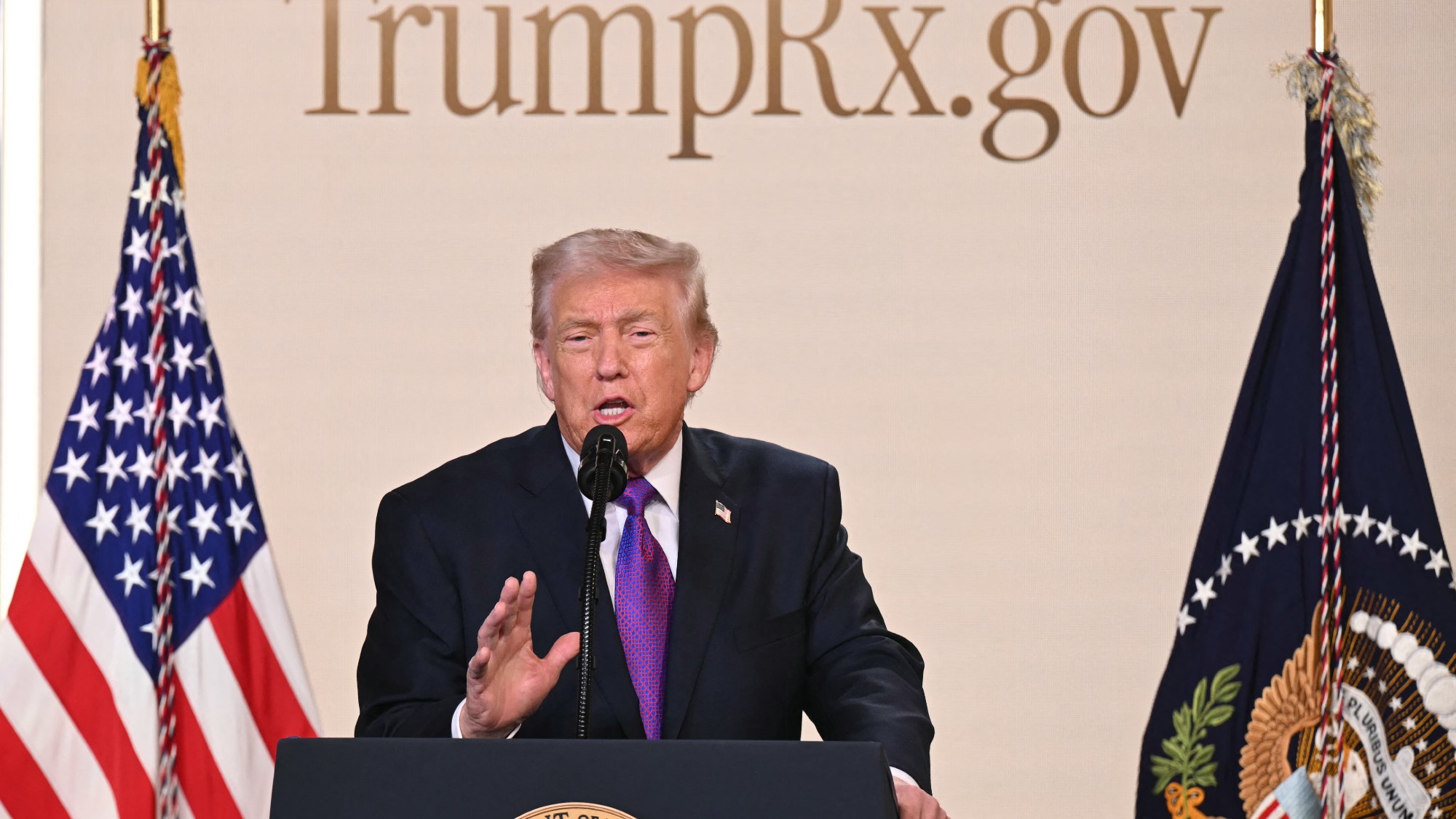

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?The Explainer The new drug-pricing site is designed to help uninsured Americans

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military