China is giving the U.S. a taste of its own medicine

Demanding certain conditions from businesses and trade partners is what the U.S. has done to other countries for decades

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We Americans tend to treat trade as a matter of purely economic exchanges. But we've recently learned that to become entangled with a country via trade almost inevitably invites broader entanglements as well — of culture, ideology, and policy. After enmeshing ourselves in trade with China, for example, we've suddenly found China using that entanglement to silence criticism of China's crackdown on Hong Kong protesters. (Or its treatment of Tibet, or its massive surveillance state.) More perniciously, China's had American institutions and companies do the silencing and surveilling for it.

In other words, if the country we're entangled with has a lot of leverage, they can force us to behave in ways we otherwise might not, and would really prefer not to.

The thing is, if you're pretty much any country other than the United States — especially a poorer or developing country — you already knew this. Because for decades, the U.S. has been doing to the world what China is currently trying to do to us.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If you're a big country with lots of consumption spending and financial capital to throw around, other countries are going to want access to your domestic market. And that will give you leverage to condition that access on certain terms. While China's rise into the ranks of global economic behemoths happened in just the last two or three decades, the U.S. has been there since the end of World War II. Through institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the U.S. has used that leverage to build the global economic and trade order to its preferences.

In the initial post-war years, this setup worked out relatively well — resuscitating the ravaged economies of Europe, and promising a prosperous new possible future for the global East and South. But then in the 1970s and 1980s, free market neoliberal ideology took over American policymaking — and by extension took over the policies America was exporting to the globe. The U.S. started forcing countries to abandon capital controls and tariffs, thus allowing the free flow of both goods and financial capital across their borders. Industrial policy and state-ownership of enterprise was discouraged, privatization and free market solutions encouraged.

This model often turned out quite badly for developing countries in particular. The end of barriers to trade and financial flows left those countries vulnerable to rich western speculators who could boost their economy by rushing in, then collapse it by rushing out just as fast. When such crises left a country saddled with unsustainable levels of foreign-denominated debt, the solution imposed by America's neoliberal hegemony was austerity, which provided the surplus cash to pay off foreign creditors, but also crushed the country's domestic economy and the livelihoods of its own citizens in the process.

Indeed, the occasional country that did resist these demands wound up raising its wealth and living standards faster — and there's no better example than China itself, which has used its own clout to pick and choose which parts of the neoliberal global trade order it does and doesn't want to cooperate with.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The modern era of big multilateral trade deals like NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) came with a similar dynamic: America has used these deals to impose pro-corporate and anti-labor regulatory structures, outsized protections for wealthy investors, and draconian intellectual property laws on the rest of the world. (Ironically, now that President Trump has pulled the U.S. out of TPP negotiations, the deal's terms have become considerably less offensive.) Trump's current trade war with China is a similar effort to impose American policy preferences on China's domestic operations: It wants China to abide by those same intellectual property standards, and to soften the rules and terms for investors.

The point of these trade deals was to entangle countries in a set of rules and arrangements that would constrain their own domestic agendas — "the creation of a set of property rights that, precisely because they span multiple sovereignties, cannot be touched by one government without inviting conflict with another," as economist J.W. Mason put it. Since the U.S. was the 800-pound gorilla in the room, no one wanted conflict with it. And thus the U.S. was able to impose its preference for neoliberalism on the world.

Now China has gotten big enough to throw its weight around as well. Of course, shutting up basketball stars and protesters and contest participants and corporate advertising campaigns that push positions China doesn't like is the imposition of political norms about acceptable discourse, as opposed to economic norms about acceptable policies. In terms of its economic relationships with the U.S., China has thus far been content to simply draw some bright lines with regard to freeing up trade and capital flows, and how much it's willing to adjust its own domestic policies to match U.S. preferences.

That particular mix of cooperation and opposition has mostly imposed its costs on the American working class, while turning out quite well for American elites. Which is why those elites only recently decided to pick a bigger fight with China — and even now, Trump's trade war is far from universally endorsed among America's economic and political power brokers.

The more interesting question is how things might evolve in the future. The neoliberal global order is not in great shape these days, beset by multiple crises. And China has taken that opportunity to begin building something akin to its own global economic order. In multiple countries, China's been quietly investing in big infrastructure projects — part of its Belt and Road initiative — to firm up and support a global system of trade routes and exchange with China at its center.

It's presented as an economic project. But observers worry China is implicitly using jobs and development to buy good will in the international community. Should China and the U.S. come to geopolitical loggerheads over any number of issues — future trade deals, the fate of political freedoms in Hong Kong, China's human rights abuses against Uighur muslims, or China's territorial claims to Tibet or the South China Sea — the U.S. may discover that China has secured itself more friends and allies than we realized.

If there's a lesson here, it may be that you should be careful how far you go in imposing your own will on other countries when you're in power. Eventually, someone else will be in power, and what you once did will set the norms for what they can do now.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

TikTok secures deal to remain in US

TikTok secures deal to remain in USSpeed Read ByteDance will form a US version of the popular video-sharing platform

-

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?Today’s Big Question Europe may impose its own tariffs

-

Shein in Paris: has the fashion capital surrendered its soul?

Shein in Paris: has the fashion capital surrendered its soul?Talking Point Despite France’s ‘virtuous rhetoric’, the nation is ‘renting out its soul to Chinese algorithms’

-

Will latest Russian sanctions finally break Putin’s resolve?

Will latest Russian sanctions finally break Putin’s resolve?Today's Big Question New restrictions have been described as a ‘punch to the gut of Moscow’s war economy’

-

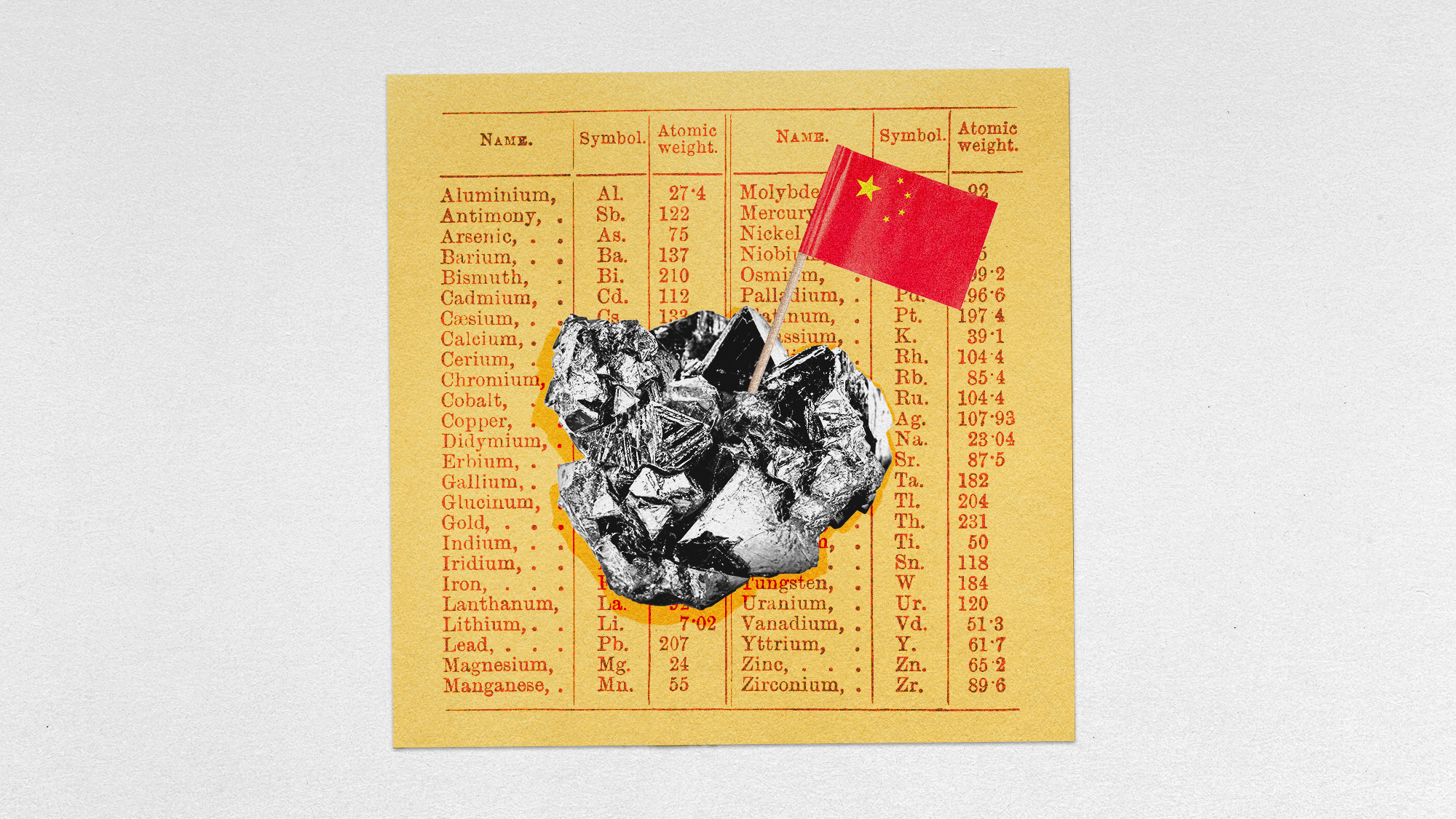

China’s rare earth controls

China’s rare earth controlsThe Explainer Beijing has shocked Washington with export restrictions on minerals used in most electronics

-

The struggles of Aston Martin: burning cash not rubber

The struggles of Aston Martin: burning cash not rubberIn the Spotlight The car manufacturer, famous for its association with the James Bond franchise, is ‘running out of road’

-

US to take 15% cut of AI chip sales to China

US to take 15% cut of AI chip sales to ChinaSpeed Read Nvidia and AMD will pay the Trump administration 15% of their revenue from selling artificial intelligence chips to China

-

Is Trump's tariffs plan working?

Is Trump's tariffs plan working?Today's Big Question Trump has touted 'victories', but inflation is the 'elephant in the room'