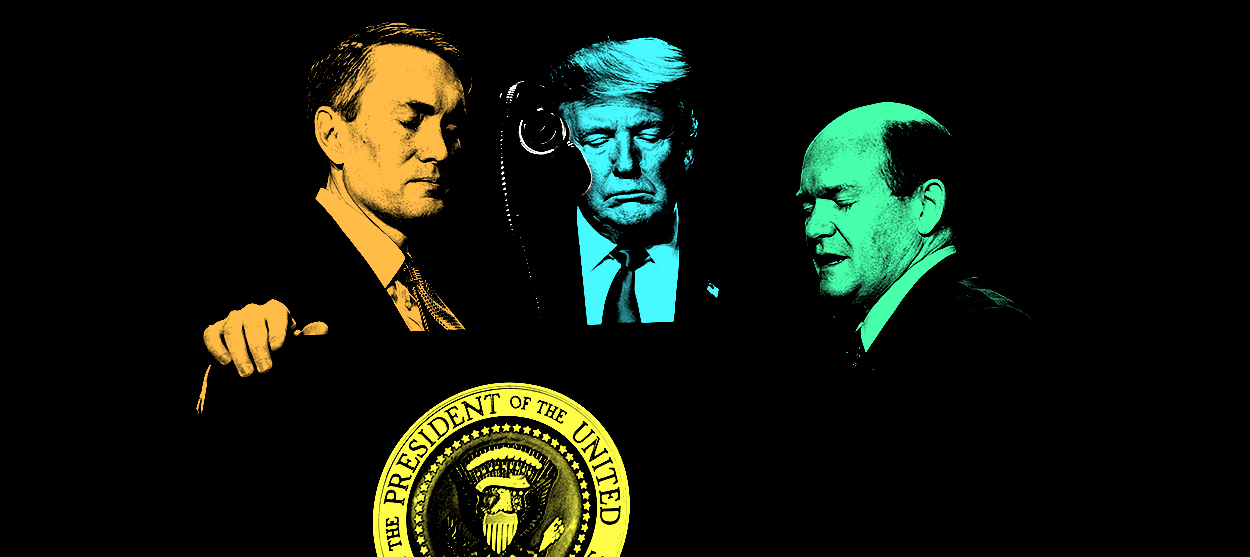

Why Trump can't believe his opponents' prayers

On Trump, Romney, and religion in our post-faith politics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The keynote speaker at the 2020 National Prayer Breakfast Thursday was Harvard's Arthur Brooks, who took as his theme a call to love — not toleration or civility but love — for our political enemies. They aren't "stupid, and they're not evil," Brooks insisted, asking his audience to reject contempt, to stop the "eye-rolling, sarcasm, derision, dismissal" and build the moral courage to stand up to our own side when goodness and truth demand it.

President Trump spoke next. "Arthur, I don't know if I agree with you, and I don't know if Arthur's gonna like what I've got to say," he began, promptly demonstrating the very contempt Brooks battled with reflections on his impeachment trial and his enemies therein. "I don't like people who use their faith as justification for doing what they know is wrong," Trump said. "Nor do I like people who say, 'I pray for you,' when they know that's not so." His apparent targets: Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), both of whom have cited their faith (Mormon and Catholic, respectively) as an influence on their politics.

Similar contempt came from Fox & Friends host Brian Kilmeade a few hours earlier. "For [Romney] to bring religion into [impeachment] — it has nothing to do with religion," Kilmeade sputtered, steamrolling cohost Steve Doocy's timid interjection that faith can guide decisions. "'My faith makes me do this?' Are you kidding?"

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Kilmeade is right, in a sense: It is increasingly strange — if not quite "unbelievable" — to hear citations of faith in politics, like those from Romney and Pelosi, in which religion serves anything but partisan ends. It is increasingly difficult not to fall into total cynicism, to assume religion in politicians' hands is only ever one more tool of political manipulation, one more way to excuse or deny wrongdoing, one more attempt to manipulate the public and each other.

That isn't because religion is absent from the public square. See, as Exhibit A, the prayer breakfast itself. The decline of religiosity (which mostly means the decline of professed Christianity) in America and the concurrent rise of the "nones" has not made faith less a part of politics. If anything, it seems to have heightened public tensions around religion. Organized faith is becoming an unfamiliar, even unintelligible sphere of life for a growing segment of the public, and many of the remaining faithful struggle to communicate their beliefs, fears, and priorities to their religiously unaffiliated neighbors. For a rising proportion of Americans, politics legitimately "has nothing to do with religion," as Kilmeade put it, so when religion appears in politics, it's inherently suspect.

Trump is a curious figure here because of his evident personal irreligiosity and concurrent reliance on white evangelicals for his political success. I expect he is perfectly sincere in his disbelief of Romney and Pelosi's sincerity: He knows he would be lying if he claimed to make a difficult political decision on the basis of faith or to pray for his political enemies, so he cannot imagine that they might be telling the truth.

"Blessed are the pure in heart," Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount, "for they will see God." Conversely, if our hearts are bent, practiced over long years to prize power, wealth, and flattery, we become unable to see God, even when he is very near. What we worship changes who we are and what we are able to understand. With enough time growing into vice, we are liable to forget that true virtue exists at all and to assume everyone, underneath their public façade of integrity, is exactly as craven as we. "To the pure all things are pure," wrote the Apostle Paul, "but to the corrupt and unbelieving nothing is pure."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I would be remiss not to mention I too have a habit of cynicism about politicians' public expressions of faith. When Pelosi spoke of praying for the president, I balanced my initial impression of her earnestness with an internal snark of, "Yeah, but are you praying the imprecatory psalms?" Though I ultimately find Romney's account of his impeachment vote convincing, Kilmeade's certainty that this was but a cloak of religiosity over established political animus has a strong pull.

Such cynicism is not without cause. Our country's cross-partisan civil religion is noxious, and faith is often misused in our politics, made a means to lower ends and shoved out the door as soon as any suggestion of unwanted moral obligation appears. Jesus is very welcome to dispense Election Day triumphs, but who does he think he is with this "love your enemies" crap? As Trump put it at the prayer breakfast, "When they impeach you for nothing, then you're supposed to like them? It's not easy, folks."

It's not easy at all, and I anticipate it will only become more difficult in politics as the evolving role of religion in America exacerbates our disintegration.

Still, Christ's instruction is not to "like" our enemies, as Trump said, which would amount to manufacturing false affection. It's to love them, as Brooks explained, to want their good. So perhaps we can risk an appearance of naivete to hope the best of them, to remember that faith is supposed to guide us toward goodness and that sometimes, even in politics, it may actually succeed.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred