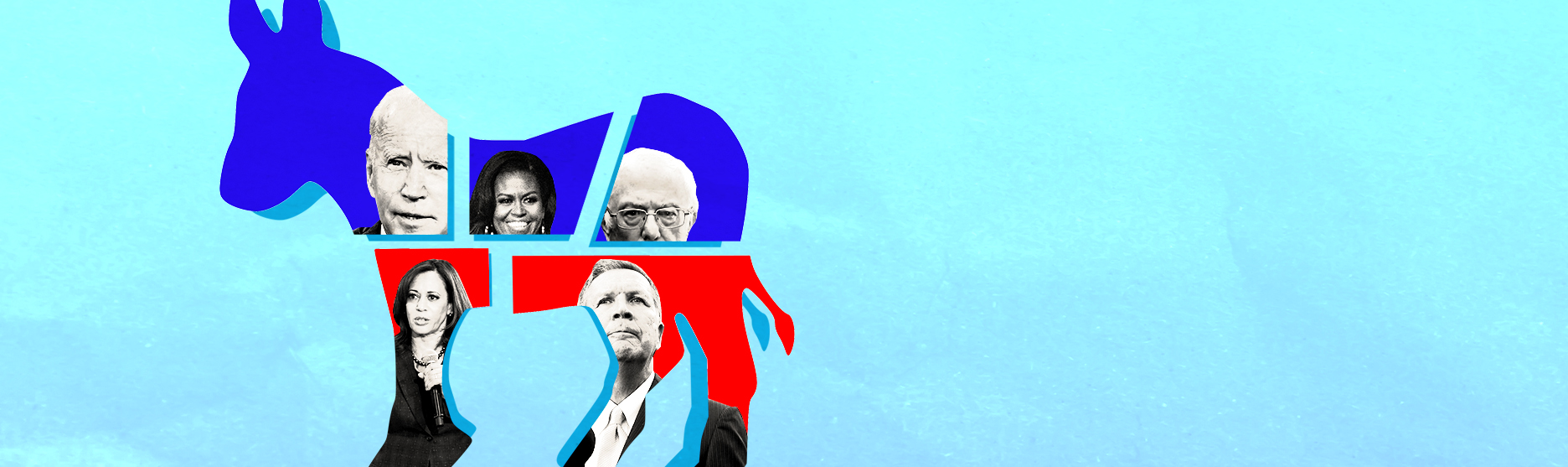

Democrats say they are unified — but around what?

The message on the opening night of the party's convention was consistent and insistent

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the first night of the multi-day infomercial we call the Democratic National Convention, a simple and powerful message was repeated over and over again: The Democratic Party is unified. Whether the speaker was a democratic socialist senator, the wife of a popular two-term president who governed from the center-left, or a prominent center-right Republican, viewers were told that Donald Trump is an atrocious president and that former Vice President Joe Biden is the perfect guy to take him down.

It's a potent message, and a crucially important one. Because the Democratic Party's greatest strength — its extra-wide, big-tent breadth, with Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders holding down the party's left wing and prominent NeverTrump Republicans welcomed to join in on the right — is also its greatest vulnerability.

What binds all the party's ideologies and all of its identity-based groups together? For now, the answer is hatred of the Republican president and a willingness to set aside intra-party differences in order to form a united front to defeat him. That might be enough to ensure that presumptive nominee Joe Biden prevails in November. But even if it works, the divisions lurking just beneath the surface and papered over with such slickly scripted perfection on Monday night will still be there, ready to burst back into the open.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That's why what wasn't said on the opening night of the convention was at least as important as what was.

What was said was consistent — and insistent. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, arguably the furthest-left member of either house of Congress, portrayed Trump as a would-be authoritarian whose malice and incompetence had made the pandemic far worse than it had to be and contributed decisively to our ongoing economic woes. He also spoke warmly about Biden's agenda and encouraged his millions of followers to put their faith in him as a force to advance their priorities for improving the country for all Americans.

Republican John Kasich described a country at a crossroads (and reinforced the message heavy-handedly by delivering his taped remarks standing at a literal crossroads). Down one path was more of Trump's divisiveness and dysfunction, with "terrible consequences for America's soul." But down the other path was Biden, who would "unite us and lead to a united America," showing all of us "a better way forward."

But it was Michelle Obama, situated at an ideological mid-point between the socialist and the moderate Republican, who really drove the message home. Much of her speech was devoted to earnestly decrying the Trump presidency and what it's doing to the country. But when it came to talking up the man who's setting out to defeat him, her rhetoric pulled back. Biden, she said, is "not perfect." But he is a Democrat, which means that his victory would mean the end of the Trump administration and the country's return to its proper path, complete with an agenda more in keeping with its values and ideals.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It was a message that demonstrated the remarkable extent to which the country's parties have come in recent years to behave like players in a parliamentary system of government — though each in a distinctive way. Republicans do it by enforcing internal ideological cohesion and discipline that is usually uncommon in two-party presidential systems. Parties in such systems typically try to win by broadening their appeal, tracking toward the center of the ideological spectrum to pick up stray votes from independents and ideologically adjacent members of the other party. Yet instead of seeking to make inroads outside their own party, Republicans act like a parliamentary party in combining internal discipline, base-mobilization, and an effort to divide the opposition. They then combine this with the skillful use of our Constitution's many counter-majoritarian institutions to wield maximal power in office and in elections.

The Democrats take a different approach. They certainly follow the tendency common to presidential systems of seeking to lure as many voters as they can from across the political spectrum. But the broader the tent becomes, the harder it can be to find any one person to hold it all together and motivate people to turn out to vote. Having an opponent as widely and intensely disliked as Trump certainly helps. But so does having a presumptive nominee, like Joe Biden, who comes as close as any candidate in recent memory of standing in for a generic Democrat — which is how most people in a parliamentary system cast their ballots. Not for the person but for the party.

That's the Democratic plan in 2020. Some voters are radical. Others are middle-of-the-road. Some are culturally conservative. Others are devoted to overthrowing entrenched structures of injustice. Some long for socialized medicine. Others favor market solutions. Will Biden really make Bernie Sanders' voters happy? Or will Biden vindicate John Kasich's faith that he won't become captive to the left? Or is Michelle Obama right that imperfect Joe Biden almost doesn't matter?

What does matter is that Donald Trump loses and a Democrat wins. This somewhat tautological proposition was the overriding message of Monday night.

What unites the Democrats? Little besides the party's faith in itself.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restored

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restoredSpeed Read The Trump administration took down displays about slavery at the President’s House Site in Philadelphia

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant U.S. intelligence

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred