Walter Sickert at Tate Britain: a ‘riveting’ retrospective of work by ‘the duke of darkness’

‘Superbly curated’ exhibition underlines fact that Sickert was a very ‘uneven’ painter

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s a fantastically sinister series of self-portraits at the start of Tate Britain’s “riveting” new Walter Sickert exhibition, said Laura Cumming in The Observer. Sickert (1860-1942) paints himself glowering in the shadows, “one eye homing in on you like a target”; hovering menacingly behind a bust of a bare-knuckle boxer; apparently barring the way between a nude model and the exit. This was how Sickert wished to be seen: as “a disrupter, an actor, a menace, a taunt”. His art is theatrical, “ostentatious, even sensational”.

At the same time, influenced by Degas and Bonnard, he was determined to record contemporary urban life – a subject he considered as worthy as any biblical episode or mythological set piece. His work conjures up a “dank land of rented rooms, sickly streets and gaslit pubs”. This “superbly curated” exhibition – the first major retrospective of his work in London for three decades – allows us to see the whole of his career. It takes in everything from his architectural paintings of northern French towns to his nudes – infamous in their day – to his extraordinary paintings based on photos from the 1930s. There’s a “haunting” portrait, for instance, of Edward VIII just before his abdication.

Sickert was “the duke of darkness”, said Alastair Smart in The Daily Telegraph. In his hands, the most wholesome of scenes were rendered shadowy; even his paintings of architectural landmarks, such as a view of the Église Saint-Jacques in Dieppe, seem to have been painted at sundown. And his “devastating” Camden Town Murder series was inspired by the real-life murder of a prostitute in the “then-insalubrious” London district, to which he had just moved.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In one work, L’Affaire de Camden Town, he paints a fully clothed man staring down “menacingly” at a naked woman on an iron-frame bed. The interior is “cramped” and “dimly lit”, the brushwork “vigorous”; you get the uneasy sense that the scene is about to burst into violence. These are the paintings that have led some “crackpots” to believe that Sickert was Jack the Ripper. “Tough viewing” though they are, the Camden paintings are standouts in a “frustrating” show that is simply too big for its own good. Containing some 150 works, it is a “trudge”. Nor does it really explain the great paradox of Sickert: how “a purveyor of stark documentary realism” was at the same time so melodramatic and theatrical.

The exhibition underlines the fact that Sickert was a very “uneven” painter, said Jackie Wullschläger in the FT. Nevertheless, he was rarely boring – and at his best, he could really dazzle. Little Dot Hetherington at the Bedford Music Hall, one of many paintings of London theatres here, “fizzes with the nervous energy of performance”. In three views of Venice’s St Mark’s Cathedral (1895-96), he paints “like a jeweller”, capturing the building’s “crosses, spires and mosaics tinged pink or emerald or gold according to time of day”. His greatest painting is 1915’s Brighton Pierrots, a depiction of a wartime seafront performance that “bursts into ecstatic, unreal chromatic harmony”.

In the past, critics have complained that Sickert wasn’t single-minded enough. Today, we’re more forgiving: born in Munich, brought up in London, he connects Britain and Europe, modernism and English realism. “Hybrid, uncertain, painting loose and free”, he is “our contemporary”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

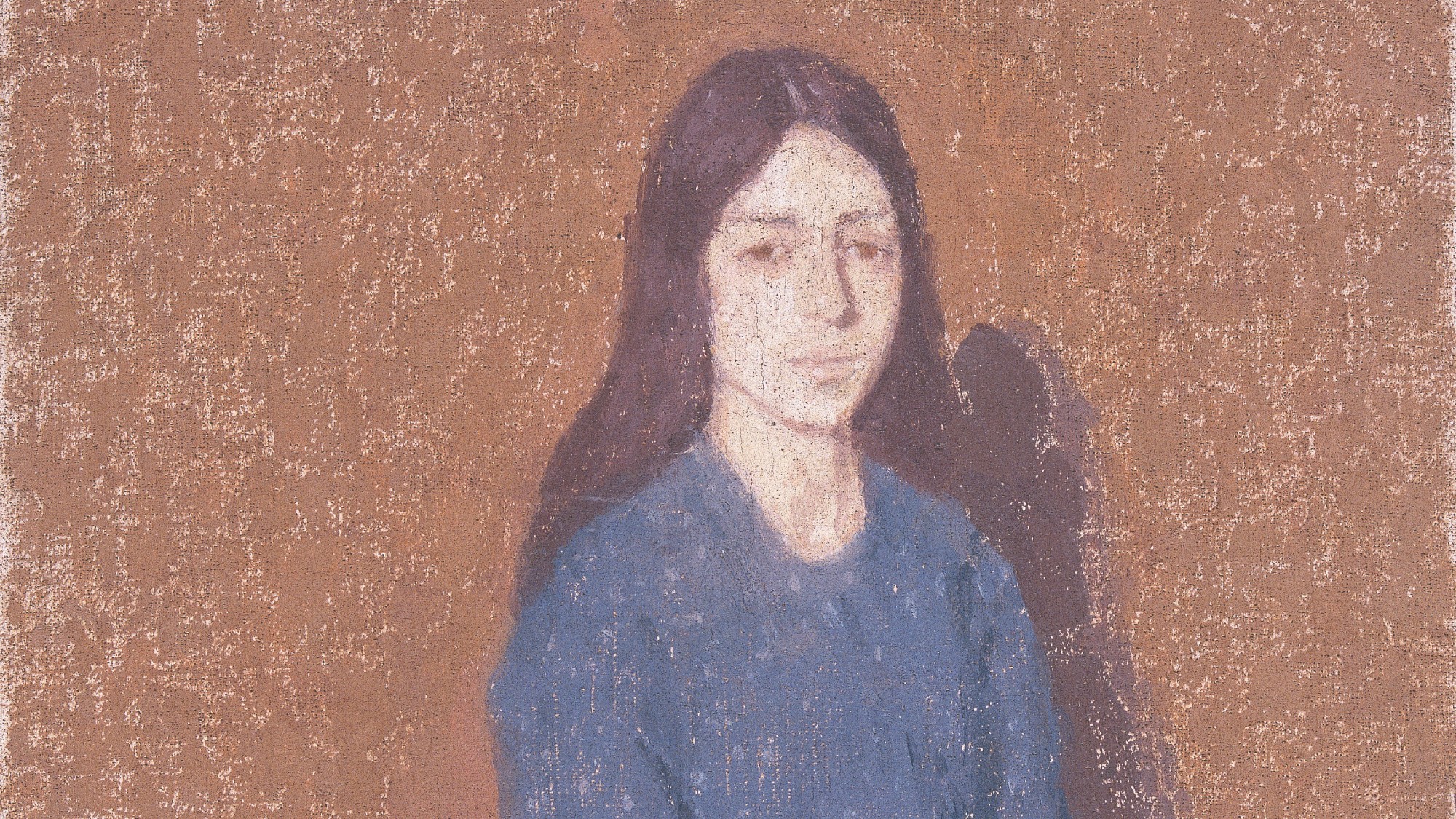

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’