Giorgio Morandi review: a ‘poetic celebration’ of a quietly fascinating artist

Estorick Collection exhibition includes some of the ‘most memorable images of 20th century Italian art’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The painter Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) was a man “so reclusive and ascetic” that some referred to him as The Monk, said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. “Forever a bachelor”, he spent almost his entire life living and working in a house shared with his mother and sisters in the northern Italian city of Bologna; he slept in the same carefully “ordered atelier” that he painted in.

If Morandi’s biography does not sound terribly exciting, nor do descriptions of his work: for the most part, with “fanatical concentration”, he gave himself over to depicting “a panoply of humdrum domestic objects”, including vases, jugs and sugar bowls, oil lamps, coffee tins, urns, “tapering liquor bottles and carafes”.

Invariably, he rendered these compositions “in a muted, chalky palette mostly of dun, ochre, and rose-beige”. Yet as unpromising as Morandi’s art might sound, his enigmatic still lifes have a transfixingly “meditative” quality that ranks them “among the most memorable images of 20th century Italian art”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This show, Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, brings together an exquisite selection of Morandi works once owned by one of his foremost collectors. Small though it is, this is “a passionate, poetic celebration” of a quietly fascinating artist.

“Morandi made the still life a 20th century art form,” said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. In a work such as his great 1936 Still Life, he ponders “the simultaneous banality and poetry” of objects including a ceramic lemon squeezer, a blue and white bowl, and a white porcelain bottle, all arranged across a “grey, featureless space”. His work is apparently simple yet very mysterious: “a silent reckoning with objects and places”.

Yet Morandi was not oblivious to the wider world: he spent much of his life under Mussolini’s tyranny, and was himself imprisoned in 1943 for his connections to the resistance. It’s hard not to detect the “monstrous shadows” of this period in his wartime work: 1941’s Still Life with Musical Instruments sees the curved body of a lute “crushed under a guitar and trumpet as if they were a heap of corpses”.

Morandi did not limit himself exclusively to still life, said Jackie Wullschläger in the FT. In a 1954 landscape, he captured a view from his studio – yet even here, the tall buildings he sees are “lined up like bottles and vases”, and are “transformed like them into monumental volumes”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

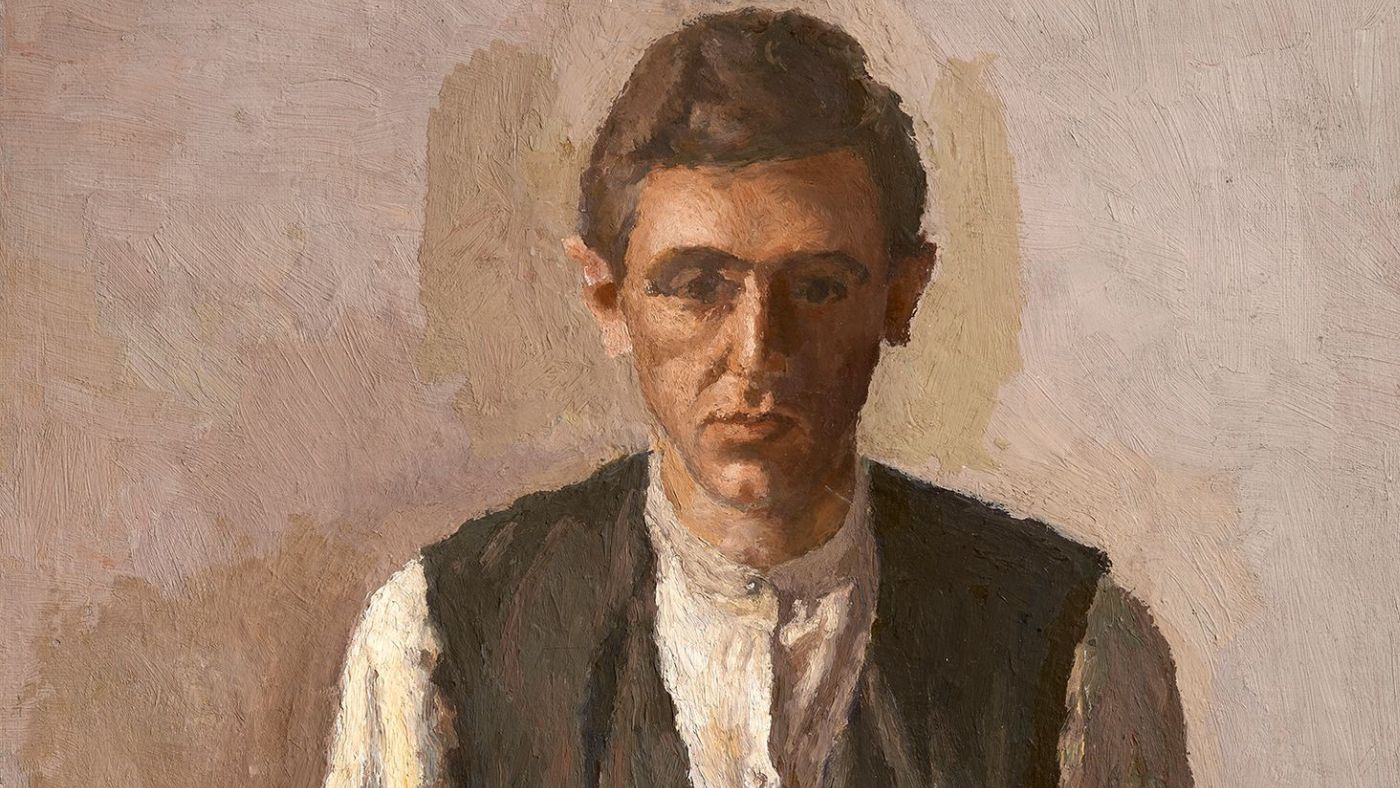

In a rare 1925 self-portrait, he presents himself as being “as enigmatically neutral as his bottles”. Morandi, it’s clear, used painting as a way to make sense of the world. “I believe that nothing can be more abstract, more unreal, than what we actually see,” he said in 1960.

So much in his art remains open to interpretation, but this fine little show beautifully encapsulates his “particular vision of hard-won serenity”.

Estorick Collection, London N1 (020-7704 9522, estorickcollection.com)

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriors

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriorsThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brand

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brandThe Week Recommends The electric SUV promises a ‘great balance between ride comfort and driving fun’

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to Lagos

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to LagosThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria