The £3 chicken: have we gone too far in our search for cheap meat?

A chicken today costs a fraction of its price 50 years ago

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ranjit Singh Boparan, who runs Britain’s biggest poultry company, recently called for a “reset” of the way we think about chicken. “Food is too cheap,” said Boparan, known as the “Chicken King”, who owns the 2 Sisters Food Group and the Bernard Matthews brand. “How can it be right that a whole chicken costs less than a pint of beer?”

He pointed to a “perfect storm” bearing down on the industry, from rising costs of feed and energy to worker shortages. But there is also a growing awareness, when it comes to the UK’s most popular meat, that animal welfare and environmental concerns can’t be addressed without affecting prices. Either way, Boparan said, “the days when you could feed a family of four with a £3 chicken are coming to an end”.

How did chicken get so cheap in the first place?

The short answer is industrial farming. Incubators, needed for raising chickens at scale, became available commercially in 1881. (The principle was understood much earlier: the Egyptians had specialised ovens for hatching eggs in 400 BC.) The discovery of vitamins and antibiotics in the early 20th century let US farmers raise chicks in factory-sized sheds – a practice that came to the UK in 1959, reducing poultry prices by nearly a third in six years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Today’s chicken industry turns feed into meat with astonishing efficiency: 1.38kg of feed per kg of live chicken, in the case of a record-breaking farm in New Zealand in 2012. Fifty years ago a medium chicken cost over £11 in today’s money, but selective breeding has led to larger, quicker-growing, bigger-breasted “broilers” (chickens bred for meat, not laying).

What did chickens look like originally?

They were scrawnier, more colourful and better at flying. As Charles Darwin first guessed, modern chickens are descended from the red junglefowl, a small, pheasant-like tropical bird native to the jungles of Southeast Asia. They’re thought to have been domesticated around 8,000 years ago, perhaps in northern Thailand. At some point, they interbred with the grey junglefowl, which introduced the gene that gives chickens yellow legs.

In time, they spread to China and then the Bronze Age Indus Valley, apparently their jumping-off point for the Middle East and Europe. Phoenician sailors spread them across the Mediterranean in the first millennium BC. There are no chickens in Homer or the Old Testament, but they feature in Plato (in the fourth century BC) and in the Gospels – notably when a cock crows after Peter disowns Jesus.

Did people always eat them?

Probably not. Archaeological evidence, in the form of ancient chicken bones, suggests that they were prized as fighting cocks, as objects of worship or sacrifice, and as exotic status symbols – like parrots or peacocks – before they were farmed for meat and eggs.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Early Roman generals consulted sacred chickens before going into battle. Julius Caesar reported that the Britons “consider it wrong” to eat them. In imperial Roman times, though, chicken became a common food. But when the empire collapsed, Europe’s well-fed chickens shrank back to the size of their Iron Age ancestors. Medieval gourmets preferred sturdier birds like geese and partridge.

Why did chicken-eating return?

It never really went away; chickens just weren’t an abundant or prestigious source of meat. People still wanted eggs, so many smallholders kept a few birds. Chicken meat was largely a seasonal by-product of the egg business: after the eggs hatched, male birds would be fed up and harvested as “spring chickens”.

In the late 19th century, the meat acquired a slightly fancier reputation. But the year-long market for broilers specifically raised for the table is recent. It began in the US in the 1930s and 1940s, and spread across the globe.

And now?

Chicken has become the most popular meat, by consumption, in the world. Last year, an estimated 130 million tonnes were eaten, an increase of nearly 100 million tonnes since 1990.

At any one time, there are more chickens on the planet than any other kind of bird: about 23.7 billion, outnumbering humans three to one. Some 50 billion chickens are slaughtered for food every year (in the UK the average broiler lives for 42 days).

Chicken production has soared with globalisation. In China, the broiler industry grew by 591% in the 20 years after 1985, and Kentucky Fried Chicken is now the nation’s biggest restaurant chain.

What about the downsides?

These are well-rehearsed. UK regulations allow a maximum of 39kg of bird per square metre for indoor-raised broiler chickens, giving each grown bird an area about the size of a piece of A4. The floors are often covered with faeces, filling the air with ammonia, damaging the chickens’ eyes, and giving them painful “hock burns”.

Modern chickens are ultra fast-growing – cheaper birds can now reach slaughter weight in five weeks – and heavy: a modern Ross 308 weighs four times as much as a comparable 1950s bird of the same breed and age. This strains their hearts, legs and bones.

Can we go on like this?

Probably not at today’s prices. In the short term, Boparan expects the cost of a chicken to rise by 10%, mostly as a result of Brexit and increased commodity prices. But the industry, which has low profit margins already, will also be squeezed by the conflicting pressures of decarbonisation and animal welfare.

Indoor-raised, fast-grown chicken has a very low carbon footprint, about a tenth that of beef. Free range birds take more energy, more land and more feed. In the long term, lab-grown meat may be one solution. Here, too, the chicken has a competitive edge: it was the first bird and the first food animal (if you exempt the Japanese pufferfish) to have its genome fully sequenced, in 2004.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classic

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classicThe Week Recommends Rupert Goold’s musical has ‘demonic razzle dazzle’ in spades

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentary

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentaryTalking Point The film has played to largely empty cinemas, but it does have one fan

-

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’The Week Recommends Richard Linklater’s homage to the French New Wave

-

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel Universe

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel UniverseThe Week Recommends A Marvel series that hasn’t much to do with superheroes

-

Is This Thing On? – Bradley Cooper’s ‘likeable and spirited’ romcom

Is This Thing On? – Bradley Cooper’s ‘likeable and spirited’ romcomThe Week Recommends ‘Refreshingly informal’ film based on the life of British comedian John Bishop

-

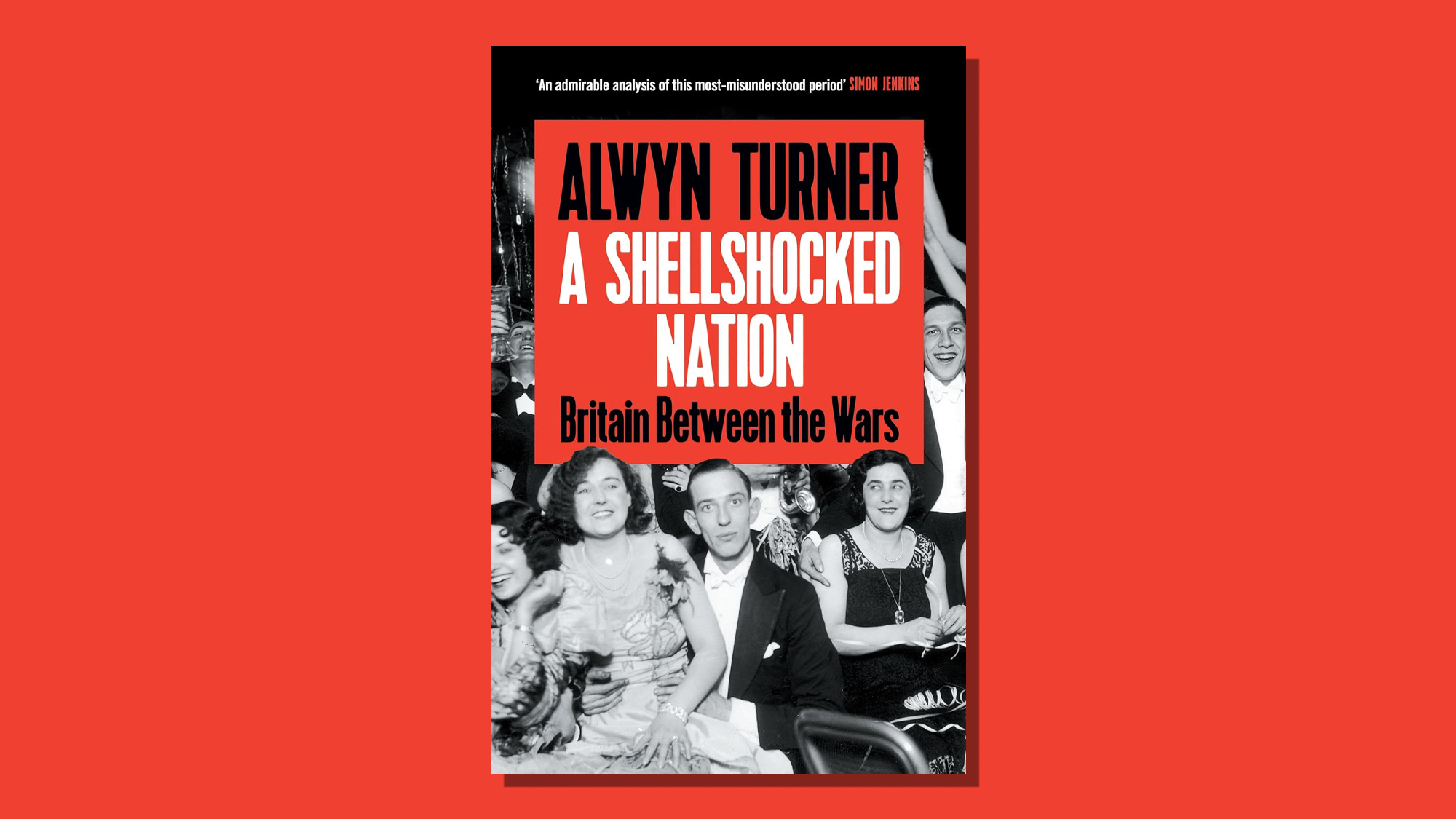

A Shellshocked Nation: Britain Between the Wars – history at its most ‘human’

A Shellshocked Nation: Britain Between the Wars – history at its most ‘human’The Week Recommends Alwyn Turner’s ‘witty and wide-ranging’ account of the interwar years