Brexit and the ECJ: What's at stake?

Theresa May seems to have softened her anti-ECJ stance in order to smooth the path to an EU trade deal

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It has been described as among the most "intractable disputes of the Brexit process" by The Times and "one of the totemic aims of Eurosceptics" by The Guardian.

Theresa May's pledge that the UK will take back "control of our laws" has been one of the defining characteristics of her unfolding Brexit plan for Britain. What had been understood by that pledge is that the European Court of Justice (ECJ) would no longer have any influence over UK law.

To many Brexiters it seemed obvious: the UK voted to leave the European Union, so there would be no reason for its court to have any say in our laws.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But Britain wants a trade deal with Europe, with "frictionless" borders, a "deep and special" partnership and a "transitional" deal that mimics much of the current arrangement, according to a Brexit position papers published last week.

Legal experts say all of that is incompatible with a clean break from the ECJ – and analysts claim that the latest UK paper, published today, concedes that point.

May is being accused by some of a U-turn and a softening of her stance to allow for a role for European courts in the UK judicial process - but the government insists it's honouring its pledge to end the "direct" jurisdiction of the ECJ after Brexit, says the BBC.

Here's everything you need to know.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why is cutting ties to the ECJ so hard?

If we want an interim post-Brexit arrangement that includes single market or customs union membership, the EU says that means accepting the oversight of the ECJ.

The Institute for Government points out that the EU negotiating position so far is that any dispute resolution mechanism under a Brexit trade treaty must enshrine the "monopoly" of the ECJ in interpreting law for EU member states.

This means no other judicial body either existing now or under a Brexit treaty could interpret and enforce law in an EU member state. So, if Britain has a dispute with an EU country that arises within that country, the ECJ would still have jurisdiction.

What does the new position paper say?

The paper, which was published by the Department for Exiting the European Union, acknowledges that under its desired Brexit deal "cross-border commerce, trade and family relationships will continue".

It also reiterates that as a non-EU country the UK will be outside of the "direct jurisdiction" of the ECJ, but that the court must remain the "ultimate arbiter of EU law within the EU".

To have cross-border relationships, especially relating to trade, parties would need to know what laws apply and, importantly, "which country's courts would deal with any dispute".

In practice, the paper says that UK and EU courts should operate within a "coherent legal framework". To that end, the government is proposing to incorporate into UK law the Rome regulations on contract law that apply across the bloc.

The paper also suggests a "reciprocal" legal cooperation agreement. This could mean companies and people are able to decide which court will hear a cross-border claim. The paper also sets out a number of precedents that cover for example the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

Where does the EFTA come into this?

The EFTA court deals with disputes related to the European Economic Area (EEA), a free trade area governed by treaty that allows non-EU states Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland membership of the EU single market.

Carl Baudenbacher, president of the EFTA court, has already said he believes it could provide the solution to the trade conundrum, and he has met with UK negotiators.

The existing operation of the court gives some indication on the future role of the ECJ.

Politico says the ECJ still rules on disputes between EEA and EU member states where the disagreement arises in an EU country, as was the case when Norway's Statoil got in a wrangle over Estonian taxes. The EFTA rules on cases arising in EEA countries.

So the EU's "monopoly" demand would be protected. But at the same time the ECJ would not have jurisdiction on matters that arose within the UK, fulfilling May's pledge.

Are there any issues with this?

If Britain sticks to its plan to formally leave the single market and customs union, it won't actually be an EFTA or EEA member. Baudenbacher doesn't believe that's a problem. He says a bespoke deal could be "docked" with his court.

More problematic is whether Brexiters would go for the option. Arch Eurosceptic and future Tory leadership contender Jacob Rees-Mogg told the Times the EFTA "takes its lead from the ECJ" and so it's "unacceptable".

The courts are, though, legally separate. He seems to be referring to the fact that much of the legal basis for the EFTA court is established in EU law.

That simply stands to reason: EEA countries are, after all, within the EU's single market.

Rees-Mogg's issue is perhaps more accurately articulated as not wanting UK trade law made or applied by a "foreign court", to use Politico's term.

But all cross-border deals have to have some legal enforcement mechanism. The World Trade Organisation has its independent arbitration panels and the free trade deal between the EU and Canada includes a new "permanent investment court".

Would we be free from the ECJ?

A strong body of legal opinion says that if we want close ties with Europe we'll need to accept some ongoing ECJ involvement, even if it's indirect. But whatever legal mechanism is chosen depends on the deal.

The UK has openly said it wants no hard borders (especially in Ireland) and a transitional deal that mimics much of the current membership arrangements.

According to Sir Paul Jenkins, who was head of the UK government's legal services for eight years, that means post-Brexit trade rules in affected areas would need to be "identical to the EU's own internal rules".

Any court or arbitration panel would therefore have to follow what the ECJ says about the EU's own rules, he told the Guardian, meaning that the UK would have the ECJ in "all but name".

In fact it would be "worse than that", the paper adds, because having left the EU the UK will no longer be able to send a judge to the ECJ, so it will "lose influence at the court".

But the government is right in saying that new domestic laws will no longer have to follow EU directives or be subject to ECJ interpretation, so it's not at all clear that any of this amounts to the U-turn that some have claimed.

-

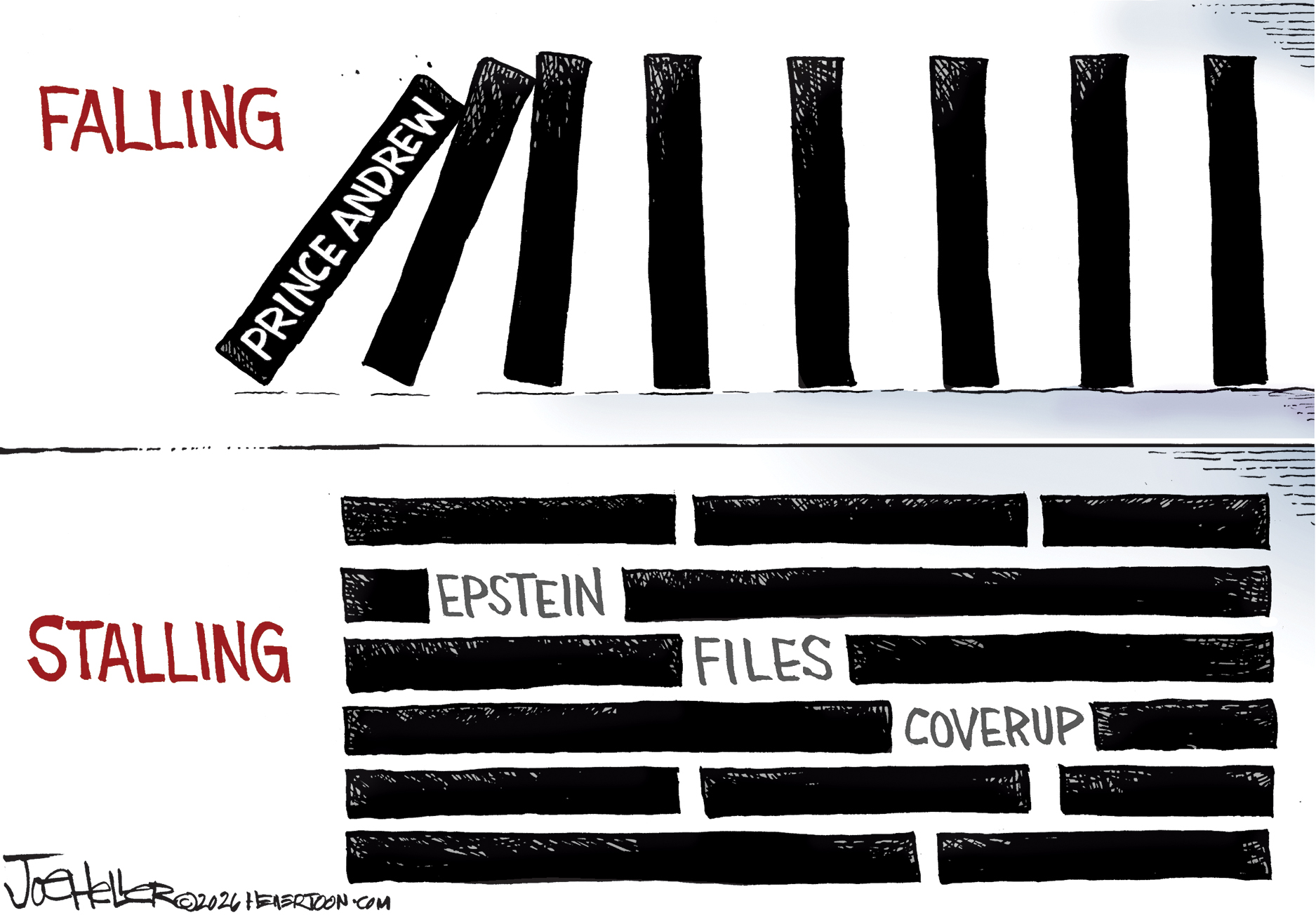

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Is Britain turning into ‘Trump’s America’?

Is Britain turning into ‘Trump’s America’?Today’s Big Question Direction of UK politics reflects influence and funding from across the pond

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance