4 places overdue for a major earthquake

Where could a major temblor hit next?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After Turkey and Syria were hit by a pair of devastating earthquakes that left tens of thousands dead, the conversation turned to whether or not such horrifying natural disasters can ever be predicted. "Turkey was 'overdue' for a big earthquake," wrote NPR, because it is in "one of the more seismically active zones on the planet." Seismologists are adamant there is no way to accurately predict when earthquakes will hit, but we do know "where the next big earthquakes will happen," writes Vox.

1. The Pacific Northwest

A large swath of the American Pacific Northwest is very likely to be hit by a major earthquake, though it may not happen for a while. A 2015 deep dive by The New Yorker examined the seldom-talked-about Cascadia Subduction Zone, which "runs for 700 miles off the coast of the Pacific Northwest, beginning near Cape Mendocino, California, continuing along Oregon and Washington, and terminating around Vancouver Island, Canada." The zone is made up of two main tectonic plates, whose convergence forms the Pacific Northwest. These plates are "stuck, wedged tight against the surface" of one another, the magazine explained, and their movement could have the propensity to cause "the worst natural disaster in the history of North America." However, for those in the area, it may be many years until a major rumble is felt. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (PNSM), which monitors fault line activity in the area, noted that "the last known megathrust earthquake in the Northwest was in January 1700, just over 300 years ago." The PNSM said that geological surveys indicated earthquakes in the area had "a return interval of 400 to 600 years." This means there may not be significant tectonic movement in the area for at least another 100 years.

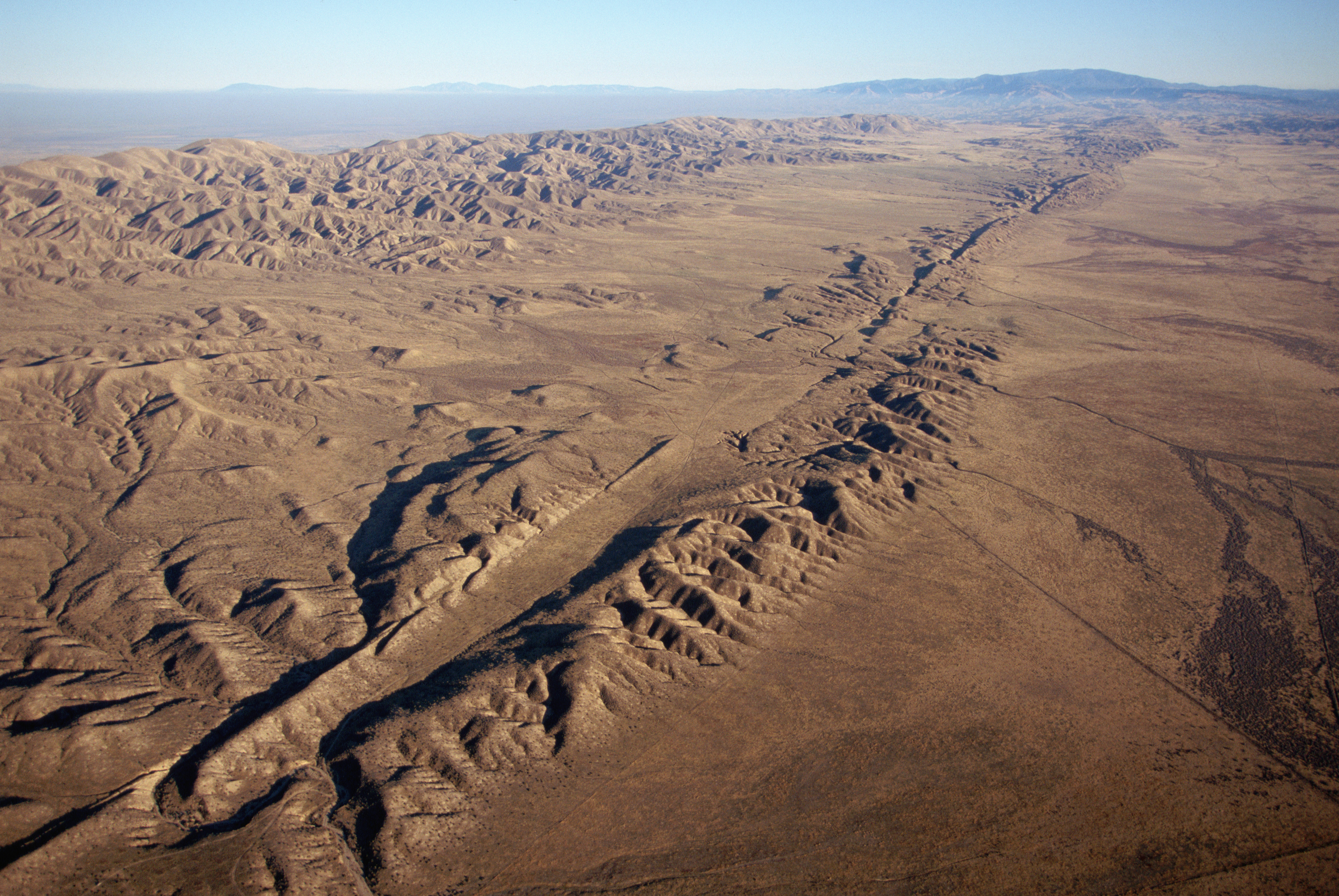

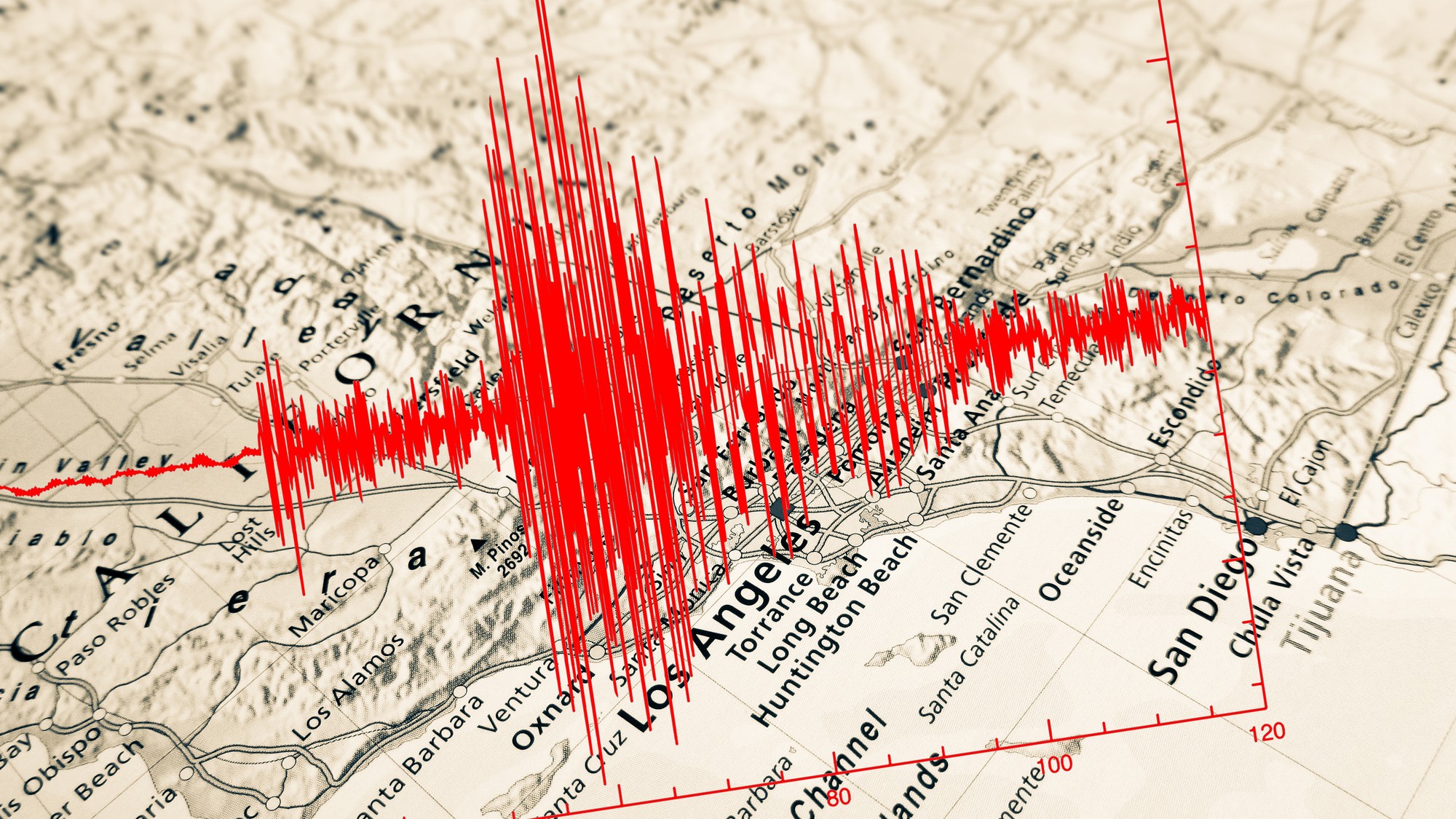

2. Southern California and the San Andreas Fault

California is ripe for a major earthquake due to its location on the San Andreas Fault. This fault, which runs more than 700 miles and stretches across much of California, was reported by Forbes as being "likely to produce what could approach a magnitude 8 earthquake." It's "not a matter of if, but when a quake of roughly this size hits Southern California." An earthquake of this scale would likely kill more than 1,800 people, injure 50,000 more, and cause up to $289 billion in damage, according to the California Earthquake Authority (CEA). However, there is obviously no set timeline for such an event. A report from the United States Geological Survey noted that the last major earthquake in the area was the 1906 San Fransisco shake. The report estimated that these types of earthquakes "occur at intervals of about 200 years," adding that "there is only a small chance (about 2 percent) that such an earthquake could occur in the next 30 years."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

3. Australia and New Zealand

Earthquakes often occur around the colloquial Ring of Fire, described by National Geographic as "a string of volcanoes and sites of seismic activity, or earthquakes, around the edges of the Pacific Ocean." According to the outlet, more than 90 percent of all earthquakes on the planet happen along this ring. This puts two countries directly in their path: Australia and New Zealand. While serious earthquakes in Australia are rare, "their implications could be massive," Australia's The Saturday Paper wrote. The 1989 Newcastle earthquake devastated the city, killing 13 people and causing an estimated $18 billion worth of damage in today's dollars. "At some point in the future, one of these magnitude five earthquakes will hit an urban center," said Januka Attanayake, a researcher at the University of Melbourne. "We know that it's going to happen, it's just a matter of time." New Zealand, meanwhile, has had many devastating earthquakes, including the 2011 Christchurch quake that killed 185 and caused widespread damage. Australia's ABC News reported that research into the Alpine Fault, which traverses New Zealand's South Island, "reveals a great earthquake, one of the biggest in New Zealand's modern history, is due." The last major Alpine earthquake was in 1717, and "it makes very big shifts, on average, about every 300 years."

4. Japan

Japan, another country along the Ring of Fire, is also due for a large tremor. A December 2021 earthquake registered at 6.1-magnitude, the strongest on the Japanese island of Akusekijima in two decades, and it will almost certainly not be the last. VICE News cited a 2018 report from seismologists that concluded there was "a 70 percent chance an 8- to 9-magnitude quake would rock Japan within the next 30 years," with the effects likely being similar to the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. The main issue, VICE reports, lies with the Nankai Trough, "an ocean-floor trough that extends from central Shizuoka prefecture to the southern island of Kyushu." This trench forms the convergence of the Phillippine and Eurasian sea plates, making it a common location of the Ring of Fire for tremors. The last major earthquake in this region was in 1946, when more than 1,300 people died. While VICE noted that these quakes "have historically happened in 100- or 150-year intervals," Australia's ABC News cited a 2022 study that found "there was a 70 percent chance a magnitude-7.3 earthquake would strike greater Tokyo before 2050." The study estimated that this mega-earthquake would destroy around 81,000 buildings, "and 4.53 million people would be left stranded, unable to return home." If this were to happen, an estimated 6,000 people would lose their lives, the study predicted.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

A rat infestation is spelling trouble for the almond industry

A rat infestation is spelling trouble for the almond industryThe Explainer The infestation has affected at least 100,000 acres in California

-

A zombie volcano is coming back to life, but there is no need to worry just yet

A zombie volcano is coming back to life, but there is no need to worry just yetUnder the radar Uturuncu's seismic activity is the result of a hydrothermal system

-

The lesser-known Elsinore fault is a risk to California

The lesser-known Elsinore fault is a risk to CaliforniaThe Explainer A powerful earthquake could be on the horizon

-

Toxic algae could be causing sea lions to attack

Toxic algae could be causing sea lions to attackIn the Spotlight A particular algae is known to make animals more aggressive

-

Recently discovered skeletons reveal new details about Pompeii

Recently discovered skeletons reveal new details about PompeiiUnder the Radar Earthquakes — not just a volcanic eruption — may have played a role in the city's destruction

-

Italy is a hotbed of volcanic activity

Italy is a hotbed of volcanic activityThe Explainer Concerns over an impending disaster are erupting

-

Extreme weather events in the last year

Extreme weather events in the last yearIn Depth Warming temperatures are fodder for dangerous weather events

-

Extreme weather events in the last year

Extreme weather events in the last yearIn Depth Extreme weather events are becoming more common thanks to climate change, and are 'affecting every corner of the world'