China's blockbusters are politically revealing. They're also a lot of fun.

You should really spend your weekend watching Chinese films

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first thing you notice about "Twister" — the big bad villain Donnie Yen fights at the climax of 2010's Ip Man 2 — is that he's huge. Towering. Made of muscles. Even his meanness is outsized. Oh, and not incidentally: He's white. Western imperialism made flesh.

"I can finish you off in two punches," he snarls at Yen.

It's probably not a spoiler to reveal that the character played by Yen — perhaps best-known to American audiences for playing a blind mystic in Rogue One — is going to kick Twister's butt. Yen must take a beating first, however. Twister, fighting in the western boxing style, does indeed treat the tinier Yen like a rag doll through the fight: When the punches land, they really land. Often as not, however, the punches don't land. Yen may be small, he may not have Twister's muscles, but he's resilient, elusive, and clever.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So of course, the ruling British imperialists — the movie takes place in Hong Kong not long after World War II — change the rules mid-fight. They cheat. No kicking, Yen is told, or you'll be disqualified and lose the match. "We cannot allow the Westerners to belittle us," laments one observer.

How Yen wins anyway: By punching Twister's mountainous biceps, then finishing him off with a flurry of punches to the face. The Westerners end up disgusted and angry; the Chinese audience carries Yen off on their shoulders. The good guys have won. The bad guys have lost.

Standard action-movie fare, right? Well, sure. "Crude nationalism," as one critic dismissed it? Undoubtedly.

There's something more going on, though. In Ip Man and many other studio films of the last 20 years, China is telling a story about what's on its mind as the country grows into a 21st-century superpower. It's a story about how the country sees itself in relation to the rest of the world. Americans who increasingly are focused on competition with China — and even contemplating the possibility of war to defend Taiwan — probably should pay attention.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Indeed, if you want to get a start on understanding the challenges of U.S.-China relations and how Beijing wants to position itself in the world, you could do worse than a movie marathon over the holidays. This is true of many world cinemas, including our own — after all, even U.S. films like the forthcoming Top Gun: Maverick have to secure Department of Defense approval of their storylines before they use military resources, with predictably USA! USA! results. But China has long been an enigma for Americans, and one more easily understood to anyone with a subscription to Netflix, HBO Max, Hulu, or Peacock.

You can begin with Jet Li's Hero, a 2002 film that functions as a sort of origin story for China itself. Then you can move on to another Li movie, Fearless, which depicts the early 20th-century demise of the Qing Dynasty and the rise of the Chinese republic. Or you might try Bodyguards and Assassins, an all-star affair set during the same time period. And if you're already a Donnie Yen fan, there's Legend of the Fist: The Return of Chen Zhen — a sequel of sorts to Bruce Lee's Fist of Fury — set right before Japan's invasion of China during the 1930s.

Many of these movies are set during a period when China was under the thumb of outsiders, including the British or Japanese. This is a painful era, a time in the country's history when it often referred to itself as "the sick man of Asia." In modern films, though, these years have been recast as the foundations of China's ultimate triumph over those interlopers — and the glorious rise of the Chinese Communist Party. The underlying message: China must face the outside world with strength or be taken advantage of once again.

"When they tell that story, that storyline is also promoted by the Chinese government to justify the rise of the communists and the rule of the Communist Party," Thomas Chen, a Lehigh University professor and expert on Chinese pop culture, told me in 2017. "Because of the Communist Party, westerners were driven out — and once again China is in the driver's seat and controls its own destiny." That message is also carefully controlled: Big studio movies in China don't get made and distributed without the government's approval, though independent filmmakers say they still have some room for careful creativity, and the country has a rich and robust history of challenging cinema.

Still, lest all this viewing starts to sound like so much grim homework, it's good to note here that these movies are genuinely entertaining, filled with expert action scenes and inventive fight choreography that can rival anything out of Hollywood. Yes, there is an element of propaganda to these flicks, but again, that's not an exclusively communist phenomenon either (just watch a John Wayne film). More to the point, like Western blockbusters, Chinese movies are also often a whole lot of fun.

It's the Ip Man quadrilogy that probably does the best job of messaging and entertainment among modern-era Chinese movies widely seen in the West. Yen plays the title character — a martial arts grandmaster who in real life was Bruce Lee's mentor — as a reluctant warrior forever pressed into action. (Sound familiar?) In the first movie, the Japanese are the villains. In the second: the British. The third? Let's just say Mike Tyson makes an appearance. And in the last installment, Ip Man travels to 1960s California, only to encounter violent anti-Chinese racism. He decides to return home to Hong Kong and teaches his son to fight.

None of this plays too heavy-handed, though. "Ip Man is popcorn cinema at its finest, full of rousing well-choreographed fights and historical drama," The Verge concluded last year.

While Yen defeats all comers in these movies, he also occasionally offers an olive branch to the rest of the world. "By fighting this match, I'm not trying to prove Chinese martial arts is better than Western boxing," he says at the end of Ip Man 2. "What I really want to say is, though people may have different status in life, everybody's dignity is the same. I hope that from this moment on, we can start to respect each other."

Whether peace and dignity end up prevailing in the real world remains to be seen. But if you don't go see these movies, they might end up finding you: The Chinese movie industry is growing by leaps and bounds. In 2021, the top-earning movie on Earth isn't F9, the latest James Bond movie, or anything from Marvel. It's The Battle at Lake Changjin, made to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, which tells the story of the Korean War battle known to Americans as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir. Needless to say, the Americans are not the good guys in this version.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

China’s burgeoning coffee culture

China’s burgeoning coffee cultureUnder The Radar Local chains are thriving as young middle-class consumers turn away from tea

-

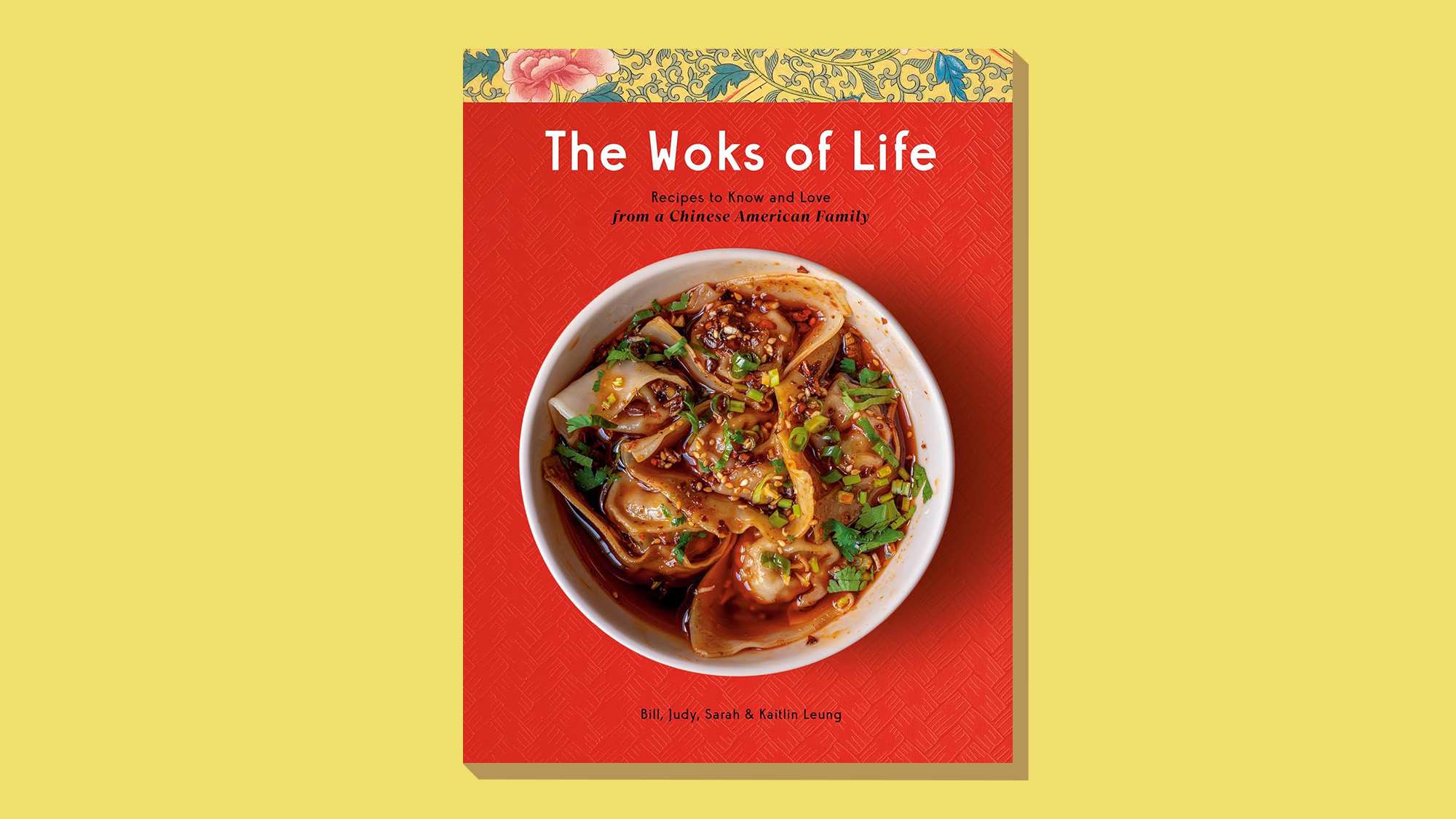

One great cookbook: ‘The Woks of Life’

One great cookbook: ‘The Woks of Life’The Week Recommends A family’s opinionated, reliable take on all kinds of Chinese cooking

-

How digital ID cards work around the world

How digital ID cards work around the worldThe Explainer Many countries use electronic ID to streamline access to services despite concern by civil rights groups they ‘shift the balance of power towards the state’

-

A guide to the Great Wall of China

A guide to the Great Wall of ChinaThe Week Recommends Experience this architectural feat

-

How to go on your own Race Across the World

How to go on your own Race Across the WorldThe Week Recommends The BBC hit show is inspiring fans to choose low-budget adventures

-

Holy mate-trimony: the rise of 'friendship marriages'

Holy mate-trimony: the rise of 'friendship marriages'Under the Radar Young people in China, Japan and the US are saying 'I do' to platonic unions, to alleviate social pressure or loneliness and access financial benefits

-

Following the Tea Horse Road in China

Following the Tea Horse Road in ChinaThe Week Recommends This network of roads and trails served as vital trading routes

-

Hands-on experiences that let travelers connect with the culture

Hands-on experiences that let travelers connect with the cultureThe Week Recommends Sharpen your sense of place through these engaging activities