How is Russia coping in the pandemic?

Plummeting oil prices are combining with Covid-19 to badly damage the Russian economy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Wednesday was supposed to be the day the Russian people voted to refresh President Vladimir Putin’s term limit, ratifying the constitutional changes he proposed in February that would have allowed him to serve as leader until 2036.

The vote was postponed in March, however, because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Since then, the virus has spread - and so has distrust at official figures. According to these numbers, around 58,000 Russians have been infected, and there have only been 513 deaths. But a poll carried out last month by the non-government, Moscow-based polling organisation Levada found that 59% of Russians did not believe or only partially believed official coronavirus information.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Even if the officials numbers are an underestimate, they still indicate that the virus is spreading at an increased rate - new infections have been much higher this week than they were before.

In particular, there is skepticism about the effect of the outbreak on hospitals, where reports of the conditions of medical personnel, as well as PPE and ventilator shortages, appear to have been quashed, reports The Washington Post.

“Russia’s hierarchy of fear - from the president down to head doctors in hospitals - appears to be stepping up its intimidation against anyone speaking out about shortages and infections in health-care ranks as the coronavirus pandemic expands across the country,” says the newspaper.

Covid-19’s effect on the economy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The coronavirus crisis is predicted to eradicate eight million jobs in Russia, and to wreak havoc on its economy.

The central government in Moscow has offered some minimal financial help to individual Russians. However, reports the BBC, “the bulk of state help and handouts is being directed at big business: more employees, more critical for Russia’s economy - and less critical of its president.”

This has led small businesses - those most vulnerable to the coronavirus lockdowns - to feel abandoned by the state and at the mercy of the pandemic-induced economic shock.

On top of the virus, as a major oil-producer whose economy is founded on its oil sector, Russia is one of the countries most affected by the oil price war and subsequent collapse of prices.

Russia’s oil wealth “hasn’t translated into significant general wealth for its 144 million citizens”, says Investopedia. Still, because of the price drop, national oil and gas revenues could fall by $165bn, meaning Moscow may have to start using the $550bn held in international reserves - money it made from oil sales - to balance the fiscal books.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

What are the ramifications for Putin and his control?

There is a belief widespread among Russians that theirs is a political system with an innate, structural reliance on strong individual leaders.

However, pandemics and global depressions present such a challenge to Putin: he justifies his power - and his continuation as president for the next 14 years - on his ability to bring stability and prosperity to the massive, often unruly country.

Much like US President Donald Trump, Putin has divested much of the decision-making to regional authorities, but he still seems unable to avoid blame for the country’s dire economic situation.

Putin’s current approval rating of 62% may sound high, but it is the lowest it has been since 2013 - a particular concern just as the vote to extend his rule looms.

There is little prospect that the pandemic might topple the government, but with the oil price drop and the piecemeal national response to the Covid-19 outbreak undercutting an already weak economy that fails to provide upward mobility for everyday Russians, the country may suffer greatly, and this will damage Putin’s mandate - very bad timing as he looks to the people to rubber-stamp his constitutional changes.

“Tens of millions of Russians have lost all or part of their incomes, sit home in isolation, and receive no financial assistance from the federal center — unlike their counterparts in the West,” says The Moscow Times.

“Now imagine if, after all that, the Kremlin suddenly announced that citizens could briefly emerge from their cages and trek to polling places to register their feelings towards those authorities. It’s an interesting prospect, isn’t it? Of course, the authorities could simply toss all the ‘no’ votes into the trash but that would be a risky move if more than, say, 50 percent of the people had opposed the amendments.”

Attempts at using foreign aid to boost domestic support

Internationally, Moscow has tried, like its neighbour China, to capitalise on the pandemic and bolster its global reputation and soft power. In early April, Russia sent a planeload of masks and protective gear to the United States, while in March it sent a similar shipment to Italy.

The PPE sent to Italy was part of an operation called “From Russia with Love” and, like the US shipment, the intended audience appeared to be in large part the Russian people.

“A video of an Italian man taking down an EU flag and replacing it with a Russian tricolor and a sign saying ‘Thank you Putin’ has played frequently on Russian TV,” says Politico, “no matter that Italian media later reported people had of received payments of €200 for filming messages of gratitude.”

Domestically, however, these gestures of foreign aid “went down badly with some Russians worried about their own supplies,” Reuters reports.

William Gritten is a London-born, New York-based strategist and writer focusing on politics and international affairs.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

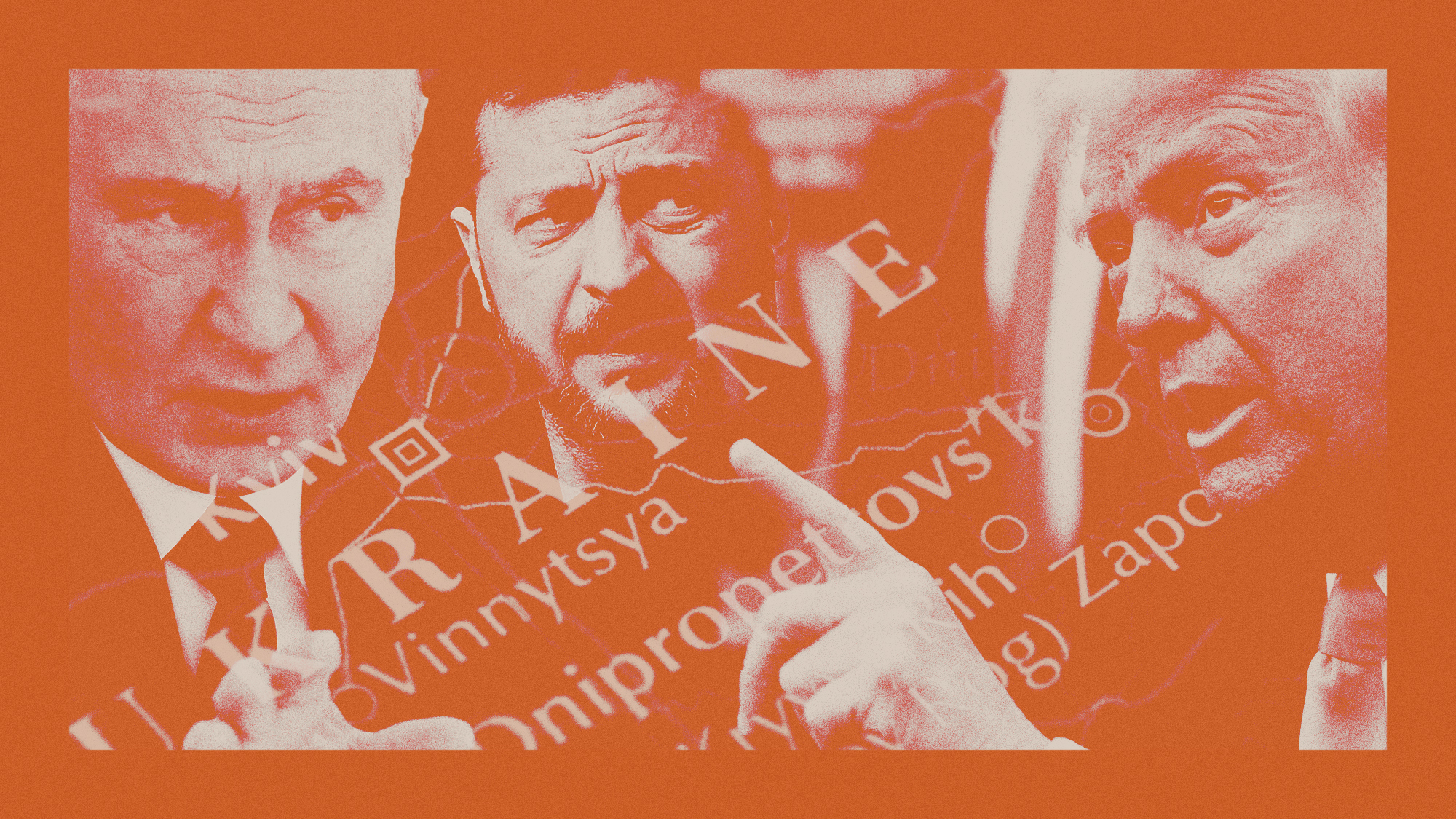

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain