3 theories on Democrats' silence about the Biden boom

The economy has real strengths. Why aren't Democrats making hay?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

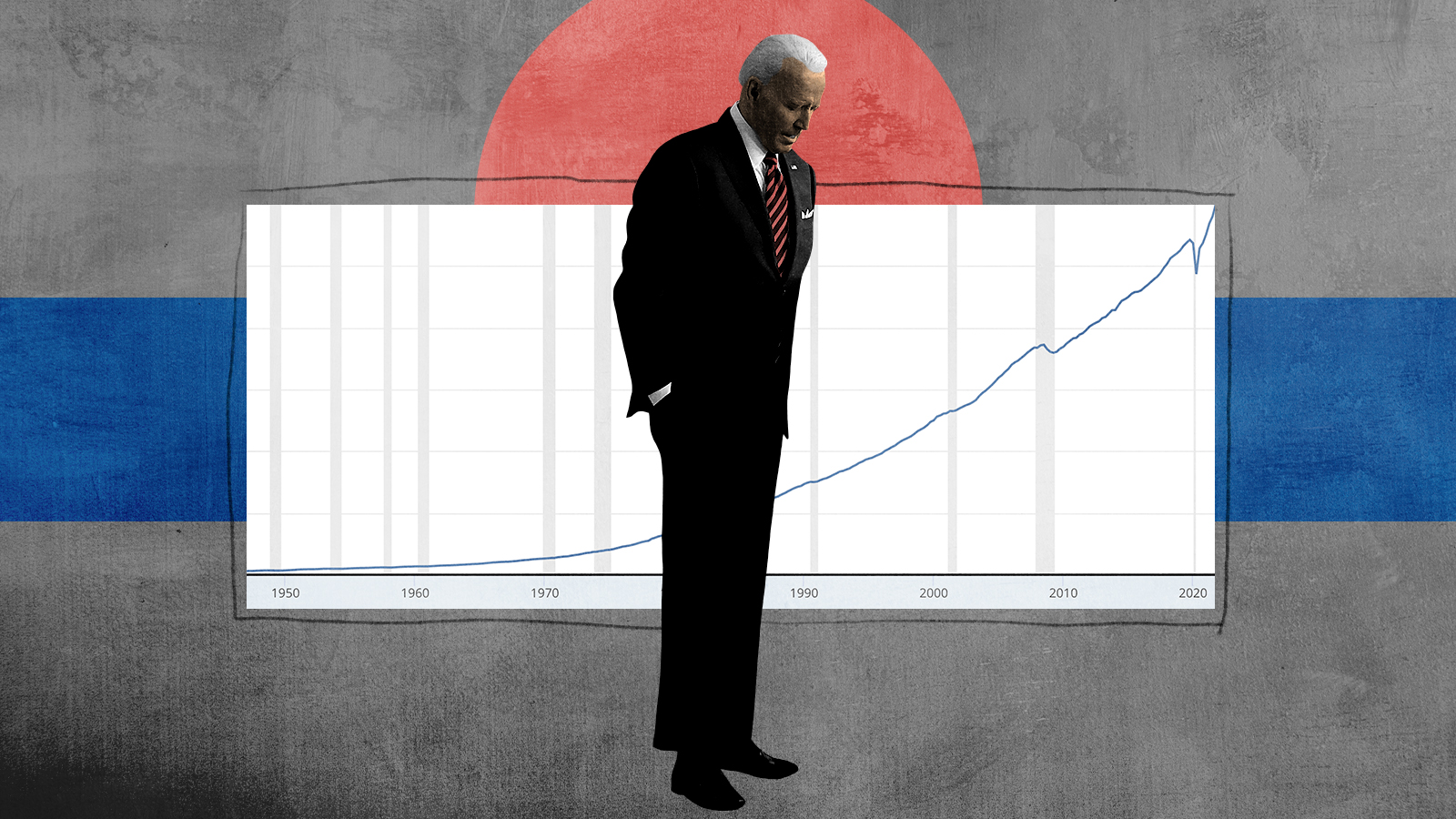

Last year, the United States economy turned in its best performance in roughly four decades. Inflation-adjusted growth was up 5.7 percent in 2021, and there were 6.4 million jobs created — the best such figures since 1984 and 1978, respectively.

Outside of perfunctory reports on those numbers Thursday, you wouldn't know it from most mainstream news. Instead there has been an endless hyper-fixation on inflation — which, while relatively high, is far better than the stagnation and mass unemployment that was the most realistic alternative.

Neither have Democrats succeeded in pushing a narrative of success. On the contrary, a recent Gallup poll found that the share of Americans naming "economic issues" as the biggest problem facing the country has roughly tripled over the year, with inflation as the most commonly mentioned particular worry. Not only are President Biden and his party not getting any credit for the recovery, they're apparently barely even trying to claim it. Why?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's hard to say precisely what's going on, given that I am not privy to internal White House discussions, but I can outline three plausible factors.

The first is that the Democratic Party and especially its intellectual elite are not at all agreed that the Biden boom is a good thing. For instance, at New York, Eric Levitz has a profile of economist Larry Summers, who has long been prominent in Democratic circles as a neoliberal deregulation guy and Machiavellian intriguer. Summers said back in March last year that the American Rescue Plan was too big, and now he's taking a victory lap.

As Levitz points out, there are a number of counterarguments to this position. Inflation is up in Europe by almost as much as here, though countries there did less stimulus. Much of the inflation likely has to do with a shift to goods and away from services, which creates price pressure because prices tend to be sticky downwards. And the pandemic is continuing to play havoc with production of key inputs, like semiconductors, as well as shipping.

Moreover, even if we stipulate for the sake of argument that there was too much economic stimulus, it was far, far better to overshoot than undershoot. A red-hot economy where wage and jobs are increasing along with prices is something the Fed can easily cool off by raising interest rates. But, as we saw during the glacial recovery after 2008, a mild depression can persist for a decade or more.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In short, Summers isn't telling the whole story. Why not? Well, on the one hand, he was more responsible than any other single person for the 2009 Recovery Act being badly undersized. That means he's on the hook for the ensuing Democratic wipeout in the 2010 midterms and the economic lost decade that followed. Saying that the current economy is uncomfortable in spots but basically pretty good would be tacitly admitting to gigantic and humiliating error — and Summers was far from the only top liberal economist or politician who made that mistake. (In the mid-2010s, then-President Barack Obama was regularly talking about the "skills gap," implying that Americans were too uneducated to get jobs instead of admitting there wasn't enough work.)

On the other hand, Summers has made much of his career working for big business, especially finance. After leaving the Obama administration, he served as a consultant for the hedge fund D.E. Shaw & Co. and the megabank Citigroup, and he sits on the board of Square and Andreessen Horowitz. (This too is common for Democratic elites.) The Biden boom isn't popular in these circles, particularly for how it has made labor so scarce.

A tight labor market undermines the status and authority of the boss — if someone can quit any job and find a new one in days, employers will be forced to treat their workers considerately, accept wage increases, or even (horror of horrors!) recognize a union drive. The business class knows perfectly well that increasing wages at the bottom, mass unionization, and low unemployment generally are all threats to their social and political position and their hugely disproportionate share of national income. They want to strangle the boom to keep the workers in line — and, plainly, so does a substantial portion of the Democrats' intellectual apparatus. A rough economy means they can continue to collect lucrative, no-show "consulting" gigs, even if they don't admit that to themselves.

The second plausible factor is the general character of the Democratic Party: timid, feckless, and above all desperate to avoid blame. For instance, rather than honestly investigating why the party did somewhat worse than predicted in the 2020 election, or even just shrugging and moving on, party leadership instantly started pointing fingers — mainly at Black Lives Matter activists. Today, we have a substantial cohort of Democratic elites who are anxiously fretting about inflation and blaming others for it rather than redirecting attention to legitimately good things about this economy.

Imagine how former President Donald Trump would have reacted to the news that Intel is building a $20 billion chip factory in Ohio. He'd mention it in every interview and press conference. He'd hold a huge rally at the factory location and post 200 deranged tweets — at least (Washed up psycho Bette Midler won't appreciate NEW American computer chip FACTORY!! #USA #TrumpBOOM). And all that in turn would drive media coverage, because whatever the president says is news, especially if it's bizarre or funny.

That leads me to the final factor: Biden himself. Over its first year, his administration has given off an unmistakable sense of drift, as if there are different internal factions fighting over the reins of power without much in the way of overall leadership.

Repeatedly the Biden White House has announced some policy stance only to grudgingly reverse course after huge backlash from its core constituencies. Biden only rarely does interviews, press conferences, or rallies, and frankly both looks and sounds quite old. His social media posts are the typical politician pablum, almost certainly written by comms staffers deliberately trying to sound calm and professional — with none of Trump's entertaining derangement or even the wacky meme humor of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Twitter account.

As a result, Biden has maybe a tenth of the command over media coverage Trump had. Nor is he using his influence to lean on Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell to not throttle the boom — on the contrary, he reportedly agrees with Powell that aggressive interest rate increases are necessary. That might easily cause a recession later this year.

With the midterms approaching, then, the Democratic Party can't decide if it wants a boom and is too wrapped up in internal disagreements and neuroses to take credit for this record-setting economy even if that decision were made. If Biden and his fellow Democrats want to fix this before the election, they best be quick.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the deep of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Democrat files to impeach RFK Jr.

Democrat files to impeach RFK Jr.Speed Read Rep. Haley Stevens filed articles of impeachment against Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.