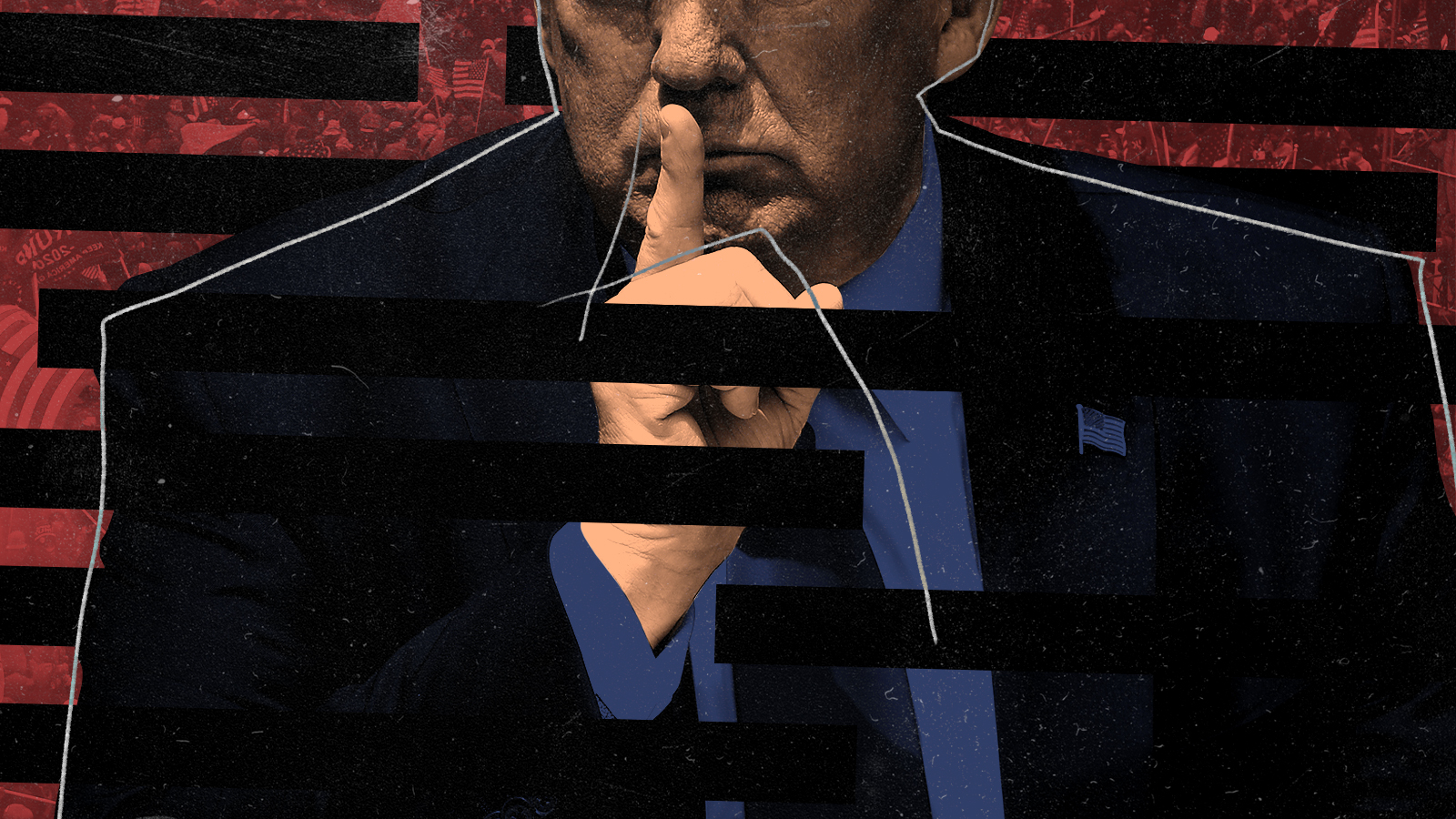

The doctrine of executive privilege has become a danger to democracy

Trump's fight to keep his coup documents hidden is a case in point

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Former President Donald Trump was just about to experience a consequence Friday when federal courts once again stepped in to delay his day of reckoning.

The congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 putsch has subpoenaed Trump administration records, and two different judges rejected his argument that the documents should be kept secret because of executive privilege. Then, on Thursday, Trump got a last-minute reprieve from the D.C. circuit court of appeals, which temporarily blocked the documents' release.

One conclusion is clear: Presidential privilege is completely out of control.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, it's uncertain as yet what will happen with Trump and the National Archives. Oral arguments in the case are scheduled for November 30, which in the glacial American legal system apparently counts as nimble action. The arguments Trump's legal team made are, of course, utterly preposterous: They say it would damage the presidency if Congress were to look at documents relating to the former president's attempt to overturn the Constitution in a coup. This is beyond bad faith.

That doesn't mean Trump won't prevail here. If his reprieve doesn't last, I suspect the reactionary Supreme Court will step in to save Trump per the tried and tested legal principle that "conservatives should not be punished when they break the law." Failing that, I expect Trump will successfully tangle things up in court long enough to eat up the rest of this congressional term. Then, Republicans will probably win the midterms, take control of one or both houses of Congress in just over a year, and shutter the Jan. 6 committee. I could be wrong, but as I've argued before, if President Biden wants ensure Congress can examine these documents, he should simply hand them over forthwith instead of waiting for a command from the courts.

As an aside, it is mind-blowing how much deference rich elites like Trump get from the legal system. If you're a poor Black kid accused of stealing a backpack, you can expect the prosecutor to try to torture a guilty plea out of you by charging you with 10 million years' worth of crimes, and then if you refuse to submit, stuffing you into pre-trial detention for years. (Only half that sentence is hyperbole.) But if you're a wealthy ex-president who sicced a violent mob on the Capitol building as part of a blatant autogolpe attempt, in full view of live, national television cameras, you get chance after chance after chance to worm out of any kind of accountability.

At any rate, all this demonstrates the extreme conditions required to even think about questioning executive privilege and presidential secrecy. And this intransigence is thorougly bipartian. On the one side, the last president tried to overturn democracy and retain power after losing an election — there can be no greater crime against the moral and political foundation of a democratic republic. On the other side, however, though both the current president and both houses of Congress agree documentation of what he did shouldn't be kept secret, the president won't take a stand for transparency. Meanwhile, our legal system is so turgid and preferential Trump is able to grind the investigation to a standstill, potentially forever.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If you read between the lines of legal scholars, it becomes clear that "executive privilege," like a great many important principles in American jurisprudence, was made up out of nothing. It's not in the Constitution. It's not in the Presidential Records Act. As an official legal principle, it comes from United States vs. Nixon (1974), in which the Supreme Court established a new formal doctrine based on its own say-so (though it said President Nixon couldn't use that doctrine to obstruct the Watergate investigation).

Cornell Law School will tell you executive privilege is rooted in the separation of powers, but it's actually rooted in the gradual expansion of executive authority. The chronically paralyzed dysfunction of Congress — supposedly the pre-eminent branch of the federal government, but now the weakest of the three by far — means power has flowed to the judiciary and the president.

Beyond its origin, the way presidents use this privilege tells you everything else you need to know about its legitimacy. Virtually the only use of executive privilege in recent history is to shield presidential wrongdoing from scrutiny.

Former President Bill Clinton invoked it to try to stop people looking into his affair with a White House intern.

Former President George W. Bush did the same to slow investigations into the friendly fire death of Pat Tillman (about which the military had lied); to stop Karl Rove from testifying about a corrupt plan to replace U.S. attorneys with partisan Republican hacks; and to gum up an investigation into his illegal warrantless wiretapping program; among other instances.

Former President Barack Obama invoked it to slow down an investigation into a deranged Department of Justice scheme that involved allowing Mexican drug cartels to traffic guns.

And Trump, of course, invoked it constantly to stymie investigations into his many, many crimes.

It's a sad irony that the constitutional framers' neurotic fear of centralized government power eventually led to the most powerful and unaccountable executive branch of any wealthy nation. If he's able to keep his probable sedition documents away from Congress, Trump's victorious invocation of executive privilege will be the culmination of a very long trend. And if we want our democracy to survive, presidential privilege as we know it must end.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.