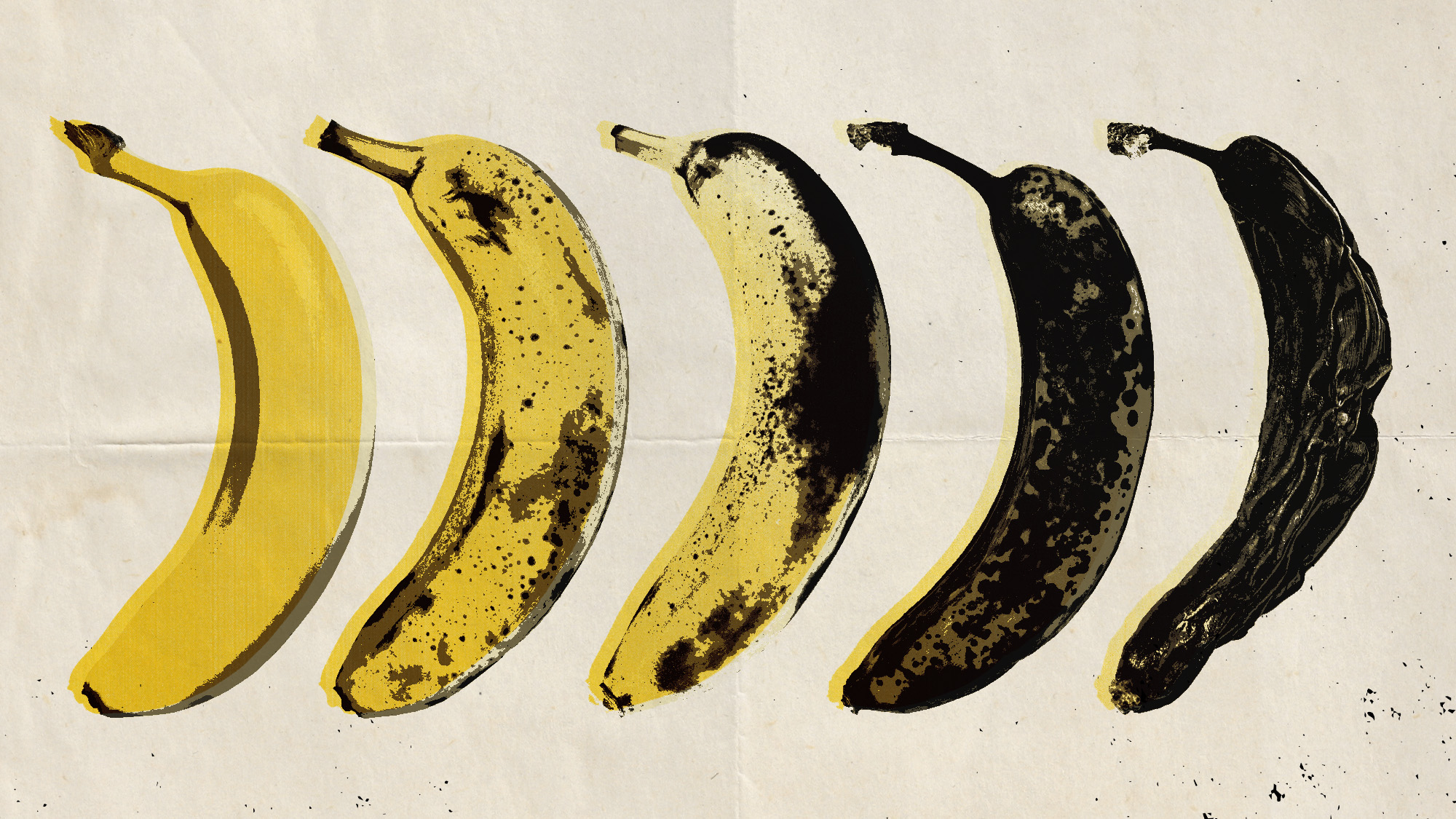

Bananas have been facing extinction. But maybe not for much longer.

Scientists may have a solution for a longstanding fungus problem

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The bananas we know and love have been at risk of extinction from a fungal disease. The good news is that scientists may have found a way to save them, according to a study published in the journal Nature Microbiology. The researchers isolated genes within the fungus that may be contributing to the disease's deadliness. Even with an avenue for controlling the disease, crop diversity could further reduce the fungus' virulence.

A banana bind

Bananas are being infected by a disease called Fusarium wilt of banana (FWB), caused by a fungal pathogen called Fusarium oxysporum TR4. This is not the first time a banana species has succumbed to the disease and gone extinct.

Today, the main variety of bananas bred and sold is the Cavendish, however, this species was only bred after the Gros Michel was wiped out by a previous version of the fungus called Fusarium oxysporum race 1. "The Cavendish variety was bred to be a disease-resistant replacement for the Gros Michel," said Popular Science. "This worked for a while, but by the 1990s, there was another outbreak of banana wilt that spread from Southeast Asia to Central America."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While bananas are facing the same variety of fungus, the TR4 species "did not evolve from the race that decimated the Gros Michel bananas," Li-Jun Ma, the senior author of the study, said in a press release. This new variety of the Fusarium fungus contains accessory genes "linked to the production of nitric oxide, which seems to be the key factor in TR4's virulence." The gas is toxic to the Cavendish banana. "This sudden burst of toxic gases facilitates infection by disarming the plant's defense system," Ma said in a piece for The Conversation.

Researchers were also able to determine that the intensity of TR4 was "greatly reduced if the two genes that control nitric oxide production were eliminated," said the press release. "Identifying these accessory genetic sequences opens up many strategic avenues to mitigate, or even control, the spread of Foc TR4," study lead author Yong Zhang said in the release. More research needs to be done to "better understand how the fungus can produce such a harmful gas without hurting itself," and to "test various ways to interrupt the production of nitric oxide and explore genes that can take the gas away before it damages plant cells," said Popular Science.

Diversify the banana breeds

The biggest problem crops like the banana are facing is the overwhelming prevalence of one breed. "When there's no diversity in a huge commercial crop, it becomes an easy target for pathogens," Ma said. Cavendish bananas are not the only existing variety of the fruit, but because of their popularity, they are bred in much larger numbers than others. In reality, planting a variety of different types of bananas creates more sustainable agriculture as well as makes diseases more difficult to spread rapidly.

The public can also play a role in encouraging more diverse agricultural practices by opting to buy different varieties of fruits and vegetables as well as supporting local produce species. "Collaboration among scientists, farmers, industry and consumers around the world can help avoid future shortages of bananas and other crops," Ma said in The Conversation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straits

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in the remote Danish protectorate shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing height

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing heightUnder the radar Its peak elevation is approximately 20 feet lower than it once was