The genocide that still haunts Russian-Ukrainian relations

Russia once tried to kill millions of Ukrainians. The nation hasn't forgotten.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

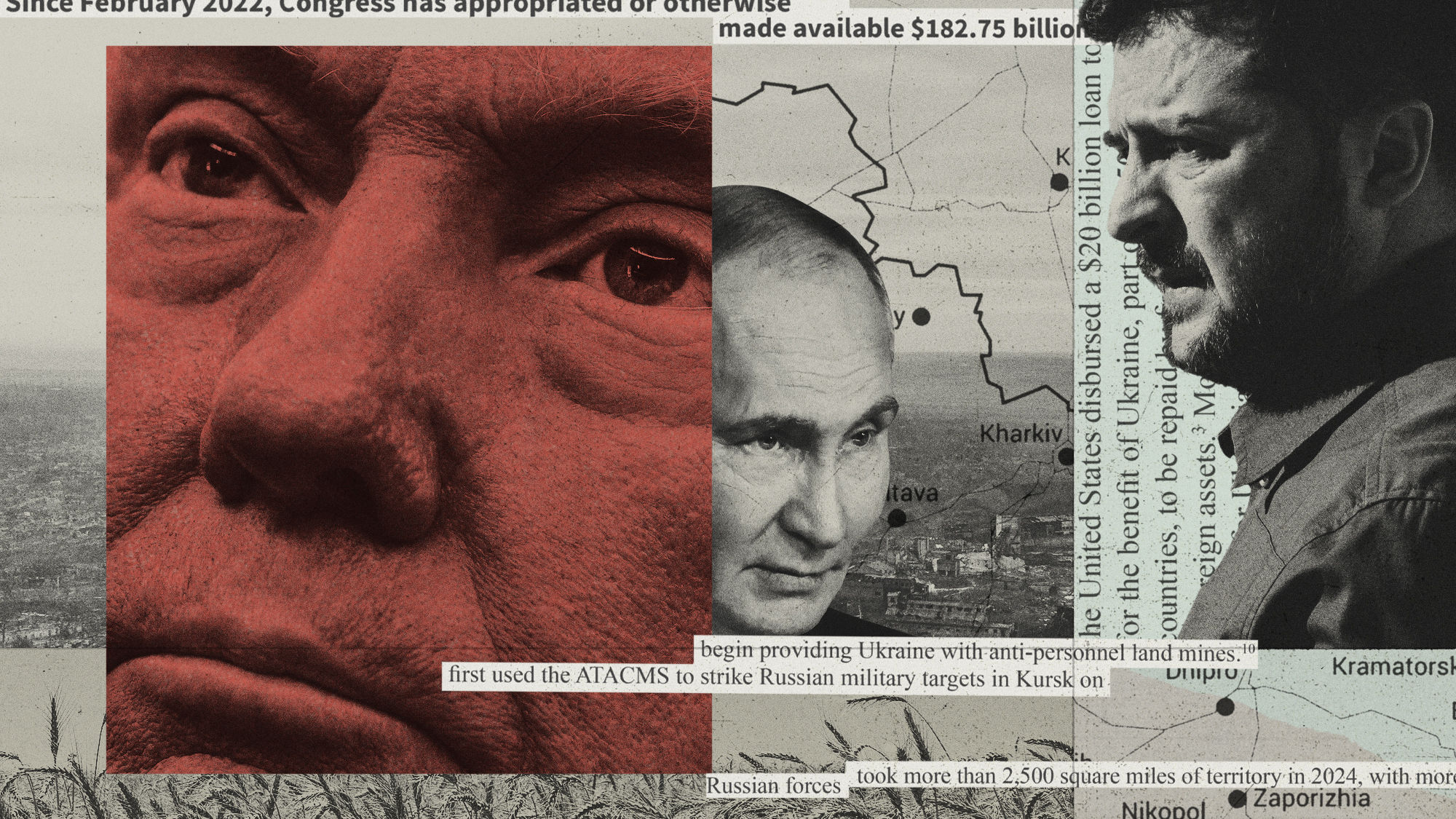

Russian President Vladimir Putin has long regretted the collapse of the Soviet Union. Unsurprisingly, that nostalgia for a lost empire isn't shared by those in Ukraine he's now trying to conquer.

In a long, rambling broadcast as the invasion was beginning last week, Putin spoke of the shared history of Russia and Ukraine and what he called the tragedy of Ukrainian independence. "From the very first steps, they began to build their statehood on the denial of everything that unites us. They tried to distort the consciousness, the historical memory of millions of people, entire generations living in Ukraine," Putin said, according to the Reuters translation.

Yet calling on those shared memories seems a strange choice, as that history includes one of the greatest crimes against humanity of the 20th century: the Holodomor.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Holodomor (the Ukrainian term for death by hunger) was a famine that killed nearly 4 million people between 1932-33. It was artificially engineered by Joseph Stalin as an attempt to bring the rebellious Soviet republic to heel, and is widely acknowledged today as a genocide against the people of Ukraine.

The great starvation took place in Ukraine's farmland, sometimes called the Black Earth due to the color of its soil. It is among the most fertile land in the world and Ukraine itself was known as the breadbasket of the Soviet Union; even today, the nation has been a source of much of the World Food Programme's aid to other countries. But at the end of the 1920s, with hunger spreading in Russia largely because of Communist policies, Stalin demanded farms and livestock be taken from their owners and collectivized, which he believed would be more modern and efficient. Many Ukrainian farmers refused to join collectives and were killed for their defiance, with thousands of others exiled to the desolation of Siberia.

The famine grew worse throughout the Soviet Union and reached its peak in 1932. In their zeal for wringing grain from Ukrainian farms, the Communists took not just every last morsel from many farmers, but even the seeds needed for the next year's planting. "The brigades took all the wheat, barley — everything — so we had nothing left," Holodomor survivor Nina Karpenko told the BBC in 2013. "Even beans that people had set aside just in case."

Finally, with nothing left to eat, people turned on each other, at times eating the corpses of their neighbors, even members of their families. Still other people resorted to murder. There are reports of mothers killing their weakest and youngest children to feed the others.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The tragedy is unimaginable. The scars on the survivors are permanent and passed down through generations of remembered trauma. But if Ukrainians have not forgotten the events of 1932-33, neither has Russia.

The Holodomor remains a politicized topic in Russia today, with the recent screening of a film in Moscow about the mass starvation broken up by masked men. Putin's government has since taken legal action against Memorial, the human rights group that was showing it, threatening to dissolve the organization. Clearly, even after 90 years, the deliberate starvation of Ukraine is not so far in the past.

Putin is right: Russia and Ukraine share a deep common history. But perhaps that history doesn't mean what he thinks it does. Rather than an argument for invasion, history may be Ukraine's greatest argument for independence.

Jason Fields is a writer, editor, podcaster, and photographer who has worked at Reuters, The New York Times, The Associated Press, and The Washington Post. He hosts the Angry Planet podcast and is the author of the historical mystery "Death in Twilight."

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

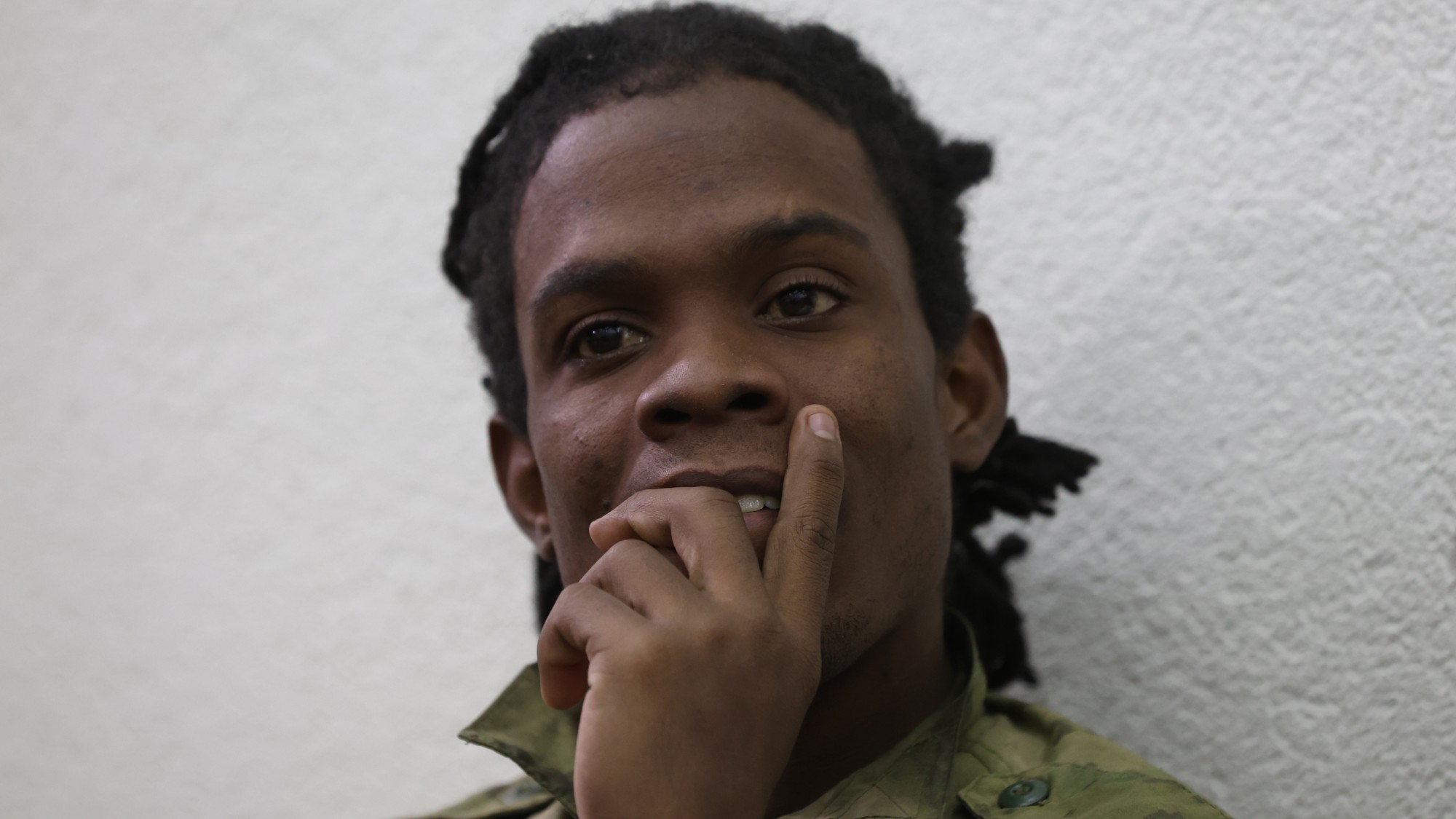

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles