Did Dry January accomplish anything?

The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A growing number of Americans gave Dry January a try this year, abstaining from alcohol in the first month of the year. Participation in the annual sobriety ritual has risen steadily since the non-profit Alcohol Change UK started it 10 years ago. More than twice as many people tried to go the month without alcohol, or with very little, this year than did in 2020. By some estimates, 1 in 5 Americans of drinking age — or more — gave Dry January a try this year.

This year, the campaign came against a backdrop of a surge in drinking during the coronavirus pandemic. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data indicates that November spending on alcoholic beverages was 3 percent higher than the previous year and 15 percent higher than the period right before the pandemic. Richard Piper, the CEO of Alcohol Change UK, told The Washington Post that the "objective of Dry January is not long-term sobriety — it's long-term control." Some people say they took the challenge hoping that cutting alcohol consumption would make them sleep and feel better. Others just wanted to see if they could do it. Did Dry January have any impact on Americans' relationship with alcohol?

It's worth abstaining to remind yourself it's possible

As her first Dry January comes to a close, says Robin Abcarian in the Los Angeles Times, "I am happy to report — as if you didn't already know — that it's possible to stop drinking even when you think you can't." For many of us, drinking has become a "mindless habit" that "interferes with a good night's sleep." Dry January is a reminder that we don't have to drink. We "choose to." And, at least those not fighting addiction, can choose to stop.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Abcarian's full disclosure: It was really a "semiarid January," broken up by wine with a niece one night, and a "couple of vodkas" a few nights later before bed, after which "I felt so lousy the next morning that it was clear why I stopped in the first place." The monthlong sobriety experiment didn't provide any "major revelations, "except that I sleep so much better without alcohol. Oh, and that it's entirely possible" do things that once seemed impossible. "Which, come to think of it, is pretty huge."

The loss of the ritual hurts

For her "damp January," "I've been sober as a nun" at home in the U.K. "with two gin and tonic-soaked nights in Cameroon (long story)," says Cathy Adams in the London Times. "So why do I feel so... awful?" It's not that I found it "boring and difficult." Having done it before, that was a given. "But as the month comes to an end, this enforced sobriety has triggered an existential tsunami I didn't see coming."

"As a working mother to a toddler," I have no "easy-off switch." I have "no clue how to decompress without a cocktail to celebrate my child having finally gone to bed." I miss the "sheer ritualism" of the nights out, the hiss of the air bubbles from a Prosecco bottle. So despite the promises that a dry month would yield "less anxiety and better sleep, I feel worse than I've felt for a long time: unstable, disorganized, emotionally adrift. I knew I liked wine, but I didn't realize how much of my emotional wellbeing derived from the grape."

Looking at your relationship with alcohol is one of many benefits

If Dry January made you ponder what you miss about your evening cocktail, it worked, says Lisa Jarvis in Bloomberg. "The biggest benefit of Dry January seems to be in forcing us all to reflect honestly on our relationship with alcohol: how often and how much we drink, our triggers for drinking more, and how alcohol might be affecting our day-to-day lives."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Emerging from the pandemic, it's important to "more deeply evaluate our habits." U.S. alcohol-related liver disease deaths "rose sharply in 2020," and a "worrisome trend in increased alcohol consumption among women" worsened that first pandemic year. Some people probably tried Dry January as a "feel-good hiatus," but experts in alcohol use disorder say "even that short break can matter for our health. Just a few weeks off from drinking can do wonders for repairing the liver, and can improve insulin resistance and blood pressure in even moderate drinkers. And people typically report tangible improvements to their daily lives, like sleeping better and losing weight."

This could be the start of a 'new Prohibition mindset'

There's no question more people are seeing the wisdom in giving Dry January a try, says Gus Carlson in The Globe and Mail. What started as a way for people to "give up drinking alcohol to atone for overindulging over the holidays" is blossoming into a modern temperance movement with power far beyond what it can do for individual drinkers.

Unlike the tobacco industry, which fought reports of smoking health risks and published ads urging people to walk "a mile for a Camel," the $88-billion-a-year U.S. beer, wine, and spirits industry "is engaging in a sort of 'if you can't beat 'em, join 'em' self-flagellation," "apologizing for, making fun of and otherwise undermining the appeal of their own core products" and pushing their non-alcoholic alternatives in a desperate attempt "to keep up with changing consumer tastes." "In the old days, you may have walked a mile for a Camel." If our "new Prohibition mindset" continues unopposed, "some day you may need to do the same for a cocktail."

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without people

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without peoplethe week recommends Solitude is different from loneliness

-

More women are using more testosterone despite limited research

More women are using more testosterone despite limited researchThe explainer There is no FDA-approved testosterone product for women

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures

-

Food may contribute more to obesity than exercise

Food may contribute more to obesity than exerciseUnder the radar The devil's in the diet

-

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?Under the radar Catching diseases, not those ever-essential Zzs

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

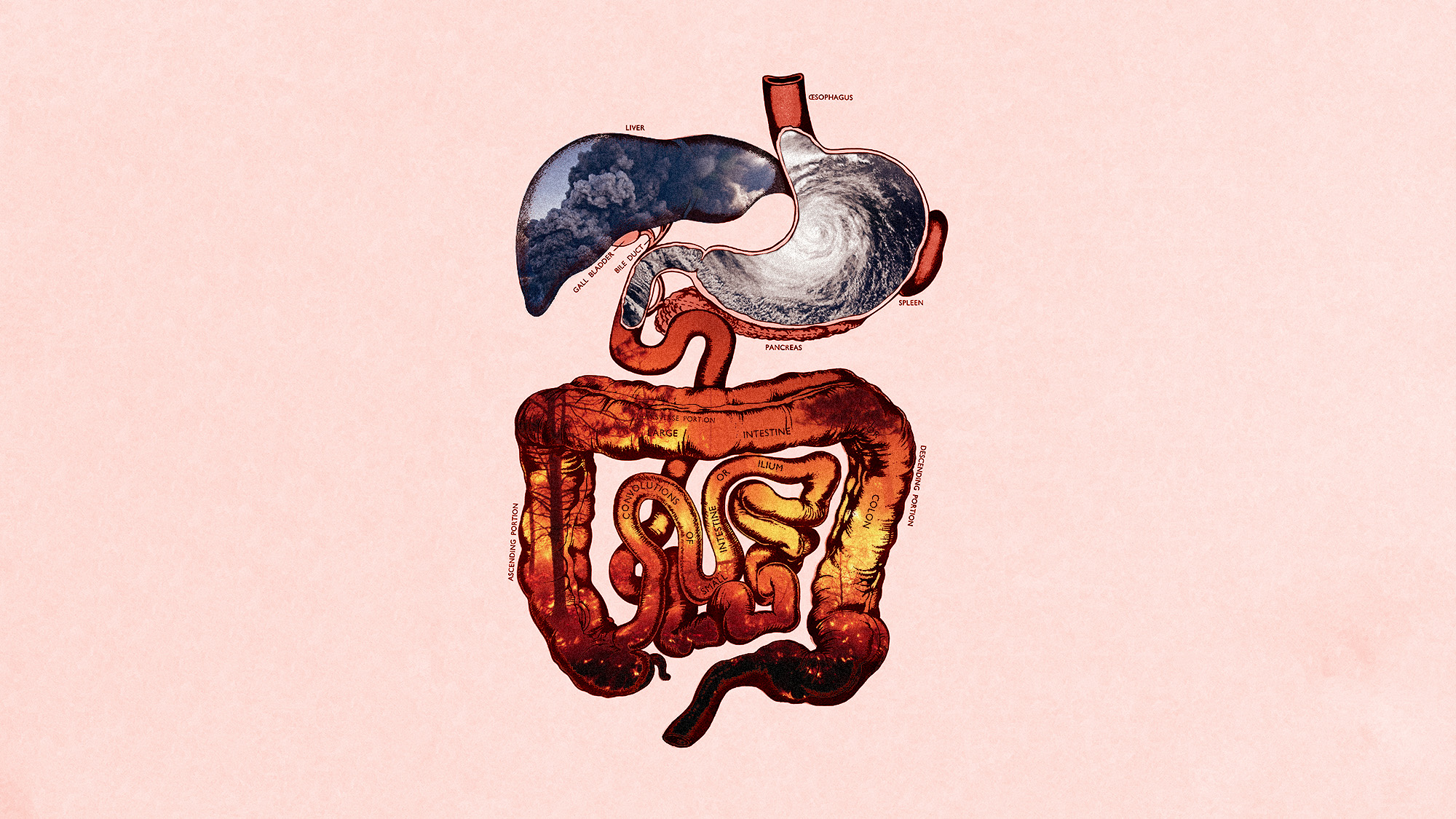

Climate change can impact our gut health

Climate change can impact our gut healthUnder the radar The gastrointestinal system is being gutted