Why are American teenagers feeling hopeless?

The youth mental health crisis, explained

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

According to a new poll from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, teenagers in America are experiencing an unprecedented mental health crisis. 29 percent of boys and 57 percent of girls reported "persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness" and levels of reported sexual violence were up significantly from pre-pandemic baselines. Those numbers were even higher for LGBTQ+ students, including 45 percent of girls in that category reporting seriously considering suicide at some point in 2021. What is driving this worrying deterioration in youth mental health, and what are experts suggesting can be done about it? Here's everything you need to know about America's youth mental crisis.

What does the data say?

The CDC's data was collected in fall 2021, as part of the agency's Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS), which has been conducting survey research since 1991. The patterns it identifies are concerning on a number of fronts beyond the toplines in media reports. Rates of attempted suicide, for example, climbed to their highest levels in more than a decade. A shocking 13 percent of high school girls and 7 percent of high school boys reported a suicide attempt in 2021. Meanwhile, 24 percent of girls reported "making a suicide plan," a 9-point increase from 2011, along with 12 percent of boys (up one point). The percentage of high school girls who contemplated suicide (30 percent) was almost double what it was in 2011. Almost one in four LGBTQ+ students were bullied or experienced sexual violence at school, and as a consequence, many chose to stay home.

The CDC report is only the latest evidence of the problem. In 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children's Hospital Association declared a "national emergency" in child and adolescent mental health. While the declaration focused on the pandemic, it also stressed that they saw an "acceleration of trends observed prior to 2020."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why have numbers spiked?

The most obvious explanation is that the COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on the well-being of young people. In many parts of the world, schools were shuttered in March 2020, social lives were upended and teenagers spent endless hours staring at screens for Zoom High School, Zoom University, and Zoom hangouts. As The Atlantic's Derek Thompson reports, "Teen anxiety and depression grew more from 2019 to 2021 than during any other two-year period on record," and it is possible these trends will reverse in the coming years as normal life resumes.

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat argues that the alarming trends in youth mental health pre-date the COVID-19 pandemic and can more usefully be blamed on the rise of social media. Social media not only contributed to a rise in social isolation, but worked poorly as a substitution for in-person interaction. He assails "its pinball motion between extremes of toxic narcissism and the solidarity of the mob, its therapy-speak unmoored from real community, its conspiracism and ideological crazes, its mimetic misery and despairing catastrophism." The argument has a certain logic that helps explain other trends in American youth culture, including a steep drop in the number of teenagers who get driver's licenses, and a sharp decline in time spent with friends. Fewer adolescents are having sex, either partnered or alone (a trend also visible in adults). These trends are not isolated to the United States — one recent U.K. study found high levels of anxiety among 16-25 year-olds and nearly a third of respondents reported that they didn't know how to make new friends.

But why would social media be making girls and LGBTQ teenagers so much more miserable than their peers? Why would boys be more or less immune to the effects of pandemic-era isolation and anxiety? These puzzling data points lead us straight into the culture wars, with conservatives arguing that "woke" ideology is confusing teenagers about their identities and upending traditional social roles and liberals arguing that the right-wing anti-gay, anti-trans fervor unleashed by the MAGA movement has teenagers scared and anxious about their future and that fears about mass shootings and climate change are inextricably linked to depression and anxiety. But again, this outbreak of sadness and despair began well before the rise of widespread media attention to non-binary and trans issues. That means that monocausal explanations might be appealing but are almost certainly wrong.

What can be done?

The alarming rise in youth mental health troubles even spurred legislators to act, or at least to contemplate acting. An existing effort to ban the social media app TikTok gained new momentum when legislators tied it to the crisis. Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.), called TikTok "digital fentanyl" and decried the "corrosive impact of constant social media use, particularly on young men and women here in America." But even a successful effort to push the China-based TikTok out of the U.S. market would only create space for another video app to take over its market share. It will ultimately be up to parents to limit their children's social media consumption, and to model less phone-centric behavior for them. Given that the social media era is less than two decades old, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that interest in these apps could collapse if evidence of their harm becomes indisputable. After all, for all of the hand-wringing about Gen Z's behavior, young people are also opting out of destructive activities like smoking, drinking, and doing drugs that were rampant when their parents were teenagers. More than anything, young people need to socialize with one another in person — the many harms of social isolation and their connection to anxiety and depression in children are by now so well-documented as to be beyond a reasonable doubt.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The American Psychological Association argues that "the separation of primary care and mental health care has created two unequal standards" and that the "mental health workforce" needs dramatic enlargement to meet the needs of young people. The CDC concurs, and lists "increasing access to needed health services" as one of its three pathways to combating youth mental health problems. It also recommends a practice of "school connectedness," that includes adult mentors and "connecting teens to their peers and communities through clubs and community outreach." A Mental Health America report recommends bringing community mental health providers into schools, which it calls a "relatively modest investment for significant gains."

A look at the risk factors identified by the U.S. surgeon general, though, should be a reminder that this will be a difficult fight. A 2021 advisory called "Protecting Youth Mental Health," pointed the finger at things like housing and financial stability along with abuse, neglect, discrimination, and loss of caregivers as key contributing factors to individual crises during the pandemic. Its recommendations include a reminder that it is "important to minimize children's exposure to violence" and that children thrive when they have a "stable and committed relationship with a supportive adult."

But these are big asks in a society that mandates zero days of paid sick leave, zero days of paid parental leave, and zero paid vacation days . In other words, it is hard to disentangle the pervasive financial precarity of American life from the youth mental health crisis, and it is also notable that these trends can be traced not just to the rise in social media use but also to the Great Recession and its aftermath, which left so many families in financial crisis.

If you or a young person that you care about is experiencing a mental health crisis, the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine has a list of resources to guide you through the process of seeking help.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without people

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without peoplethe week recommends Solitude is different from loneliness

-

More women are using more testosterone despite limited research

More women are using more testosterone despite limited researchThe explainer There is no FDA-approved testosterone product for women

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures

-

Food may contribute more to obesity than exercise

Food may contribute more to obesity than exerciseUnder the radar The devil's in the diet

-

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?Under the radar Catching diseases, not those ever-essential Zzs

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

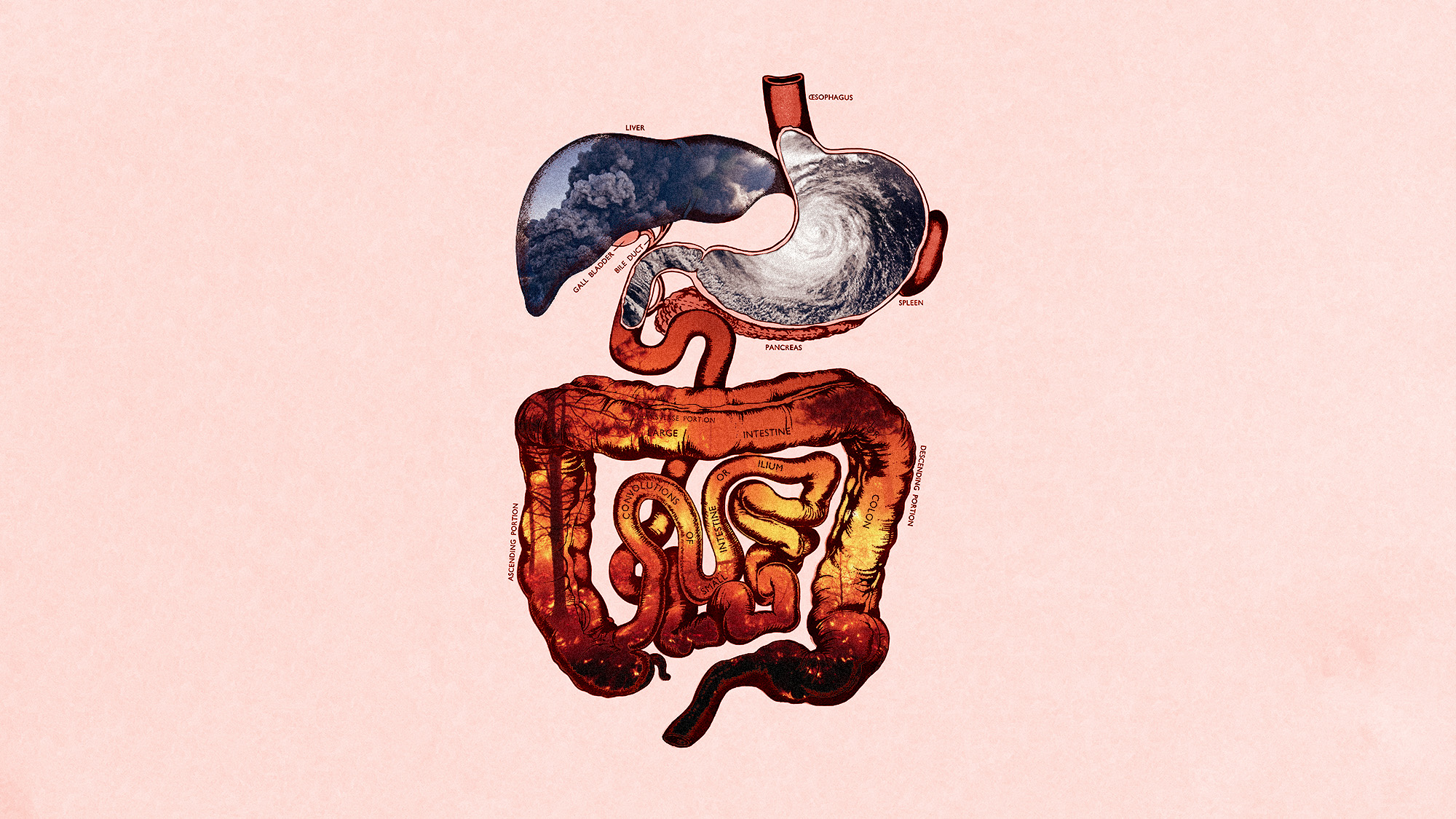

Climate change can impact our gut health

Climate change can impact our gut healthUnder the radar The gastrointestinal system is being gutted