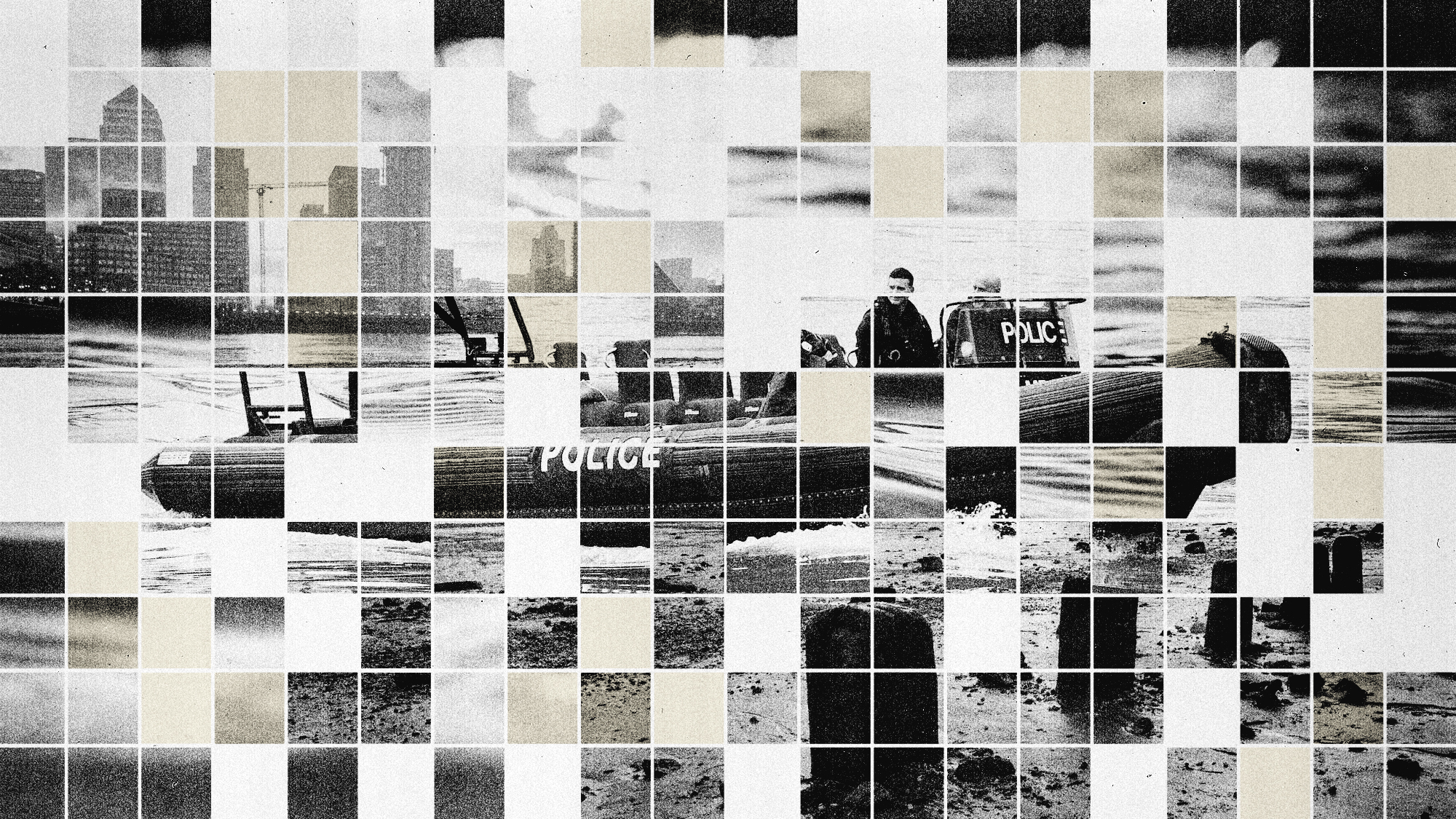

The dangerous search for bodies in the River Thames

Retrieving corpses is difficult due to 'massive' tidal range and fast current of deep, dark water

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The news that two male bodies were recovered from the River Thames while the search for chemical attack suspect Abdul Ezedi was under way could easily have been overlooked.

Neither body was Ezedi's. He was last seen "leaning over the railings" on London's Chelsea Bridge on the night of the attack in Clapham in January, according to Metropolitan Police. The force said its main working hypothesis was that Ezedi had "gone into" the river. The two bodies found are being treated as unexpected deaths, pending inquiries, but the discovery highlights the "gruesome" reality of the river, said The Guardian's Caroline Davies.

On average, 25 bodies have been retrieved from the 47-mile urban stretch of the Thames each year since 2012, according to Metropolitan police figures, most found washed up on mudflats or spotted floating in the water. But along the full 213-mile course of the river, "a dead body is washed up once a week on average", wrote Davies. "Few make the headlines."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is the main cause of death?

"If you spend enough time on the Thames, you will eventually come across human remains," wrote river mudlark Lara Maiklem in The Spectator. It is "a river of lost souls, filled with suicides, battles, burials, murders and accidents".

The number of corpses that wash up every year is "positively Dickensian", wrote William Boyd in the Financial Times, referring to Charles Dickens's "Our Mutual Friend" (1865), which begins with a body being hauled from the Thames one night. But most of the deaths are accidental: people caught by the rising tide or by the force of the current.

The initial shock of cold water is often the cause of drowning, said Davies. "The muscles freeze, the mouth opens, they take in the water and they sink to the bottom. Only with decomposition will they begin to float."

Even in summer, people start to suffer from the effects of cold water shock within three minutes, according to Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) figures reported in Metro. Last year, at least 109 people went into the water and survived, according to Port of London Authority (PLA) data, while 27 died.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Neil Withers, RNLI Area Lifesaving Manager for the Thames, said swimmers could be swept hundreds of metres away just "seconds" after entering the river.

Very few of the bodies are homicide victims. The tides mean the bodies could "pop up" unexpectedly, said Davies. But "with advances in DNA and better reporting of missing persons, almost all are identified".

How are the bodies found and recovered?

The Met's Marine Policing Unit (MPU) is responsible for retrieving the bodies found along the urban stretch of the Thames, between Dartford and Hampton Court, as well as the lakes, reservoirs and 200 miles of canal in Greater London.

But the enormously strong tide makes retrieval difficult. "If someone jumps at Westminster Bridge, depending on weather, within 10 seconds they could be 100 metres up or downriver," said Davies.

The MPU's team of 10 divers can therefore only go into the Thames in certain circumstances. The river is also extremely dark and deep: up to 20 metres in places. Even if police are aware of where and when someone went into the water, the MPU must typically "wait for the body to pop up" after decomposing, or carry out a "low water search" for three days, sometimes finding bodies on the mudflats.

Some corpses are found after becoming tangled in old piers; others are caught in "rubbish catchers, which are like big bins with mesh to catch river rubbish".

Despite popular folklore suggesting more likely places for bodies to wash up, such as Dead Man's Hole at Tower Bridge, there are no predictable locations, said BNN Breaking. "The river's strong tide and dangerous environment make it a formidable adversary, often leaving bodies severely mutilated and difficult to recover."

However, those washed down river "tend to pool at the great U-bend of the Isle of Dogs", said Boyd.

"At this time of year, the Thames is very fast flowing, very wide and full of lots of snags," said Jon Savell, the Met commander in charge of the Ezedi inquiry.

"It is quite likely that if he has gone in the water, he won't appear for maybe up to a month and it's not beyond possibility that he may never actually surface."

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

Nitazene is quietly increasing opioid deaths

Nitazene is quietly increasing opioid deathsThe explainer The drug is usually consumed accidentally

-

The plant-based portfolio diet invests in your heart’s health

The plant-based portfolio diet invests in your heart’s healthThe Explainer Its guidelines are flexible and vegan-friendly

-

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without people

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without peoplethe week recommends Solitude is different from loneliness

-

More women are using more testosterone despite limited research

More women are using more testosterone despite limited researchThe explainer There is no FDA-approved testosterone product for women

-

Doctors sound the alarm about insurance company ‘downcoding’

Doctors sound the alarm about insurance company ‘downcoding’The Explainer ‘It’s blatantly disrespectful,’ one doctor said