Bridgefy: how Hong Kong protesters are using Bluetooth to dodge surveillance

Privacy app lets users message each other without Wi-Fi connection

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong are using a new private messaging service in a bid to avoid being tracked by local authorities.

San Francisco-based firm Bridgefy’s app doesn’t require a Wi-Fi connection to operate, instead allowing users to chat with each other through a more private Bluetooth connection.

Hong Kong protestors “keen to avoid any interference” from the local authorities have flocked to Bridgefy in droves, Sky News reports. Indeed, data from app analysts Apptopia shows that downloads of the software has surged by almost 4,000% in the past two months.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But while Bridgefy may add a layer of security, some experts warn that the technology isn’t foolproof.

What is Bridgefy?

Unlike chat apps such as WeChat - China’s equivalent to Facebook - and WhatsApp, Bridgefy is an instant massaging service that doesn’t rely on Wi-Fi or mobile networks to operate.

Instead, the service “create its networks” through Bluetooth, says TechCrunch. Although the technology has a maximum range of 100 metres (330ft), Bridgefy uses user handsets to boost - or bridge - the connection to other devices.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It’s not just a peer-to-peer service, either. The app can also be used by a single user to spread messages to groups of people in the nearby vicinity.

In the case of the ongoing protests in the Chinese-ruled territory, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators can communicate with each other and arrange gatherings via Bridgefy thanks to their close proximity to each other, bypassing the need to create dedicated WhatsApp or WeChat groups.

How is the government tracking protestors?

Although there’s been no official word on how authorities are digitally monitoring the protests, reports suggest that Beijing is using tech systems to keep a close eye on the demonstrations.

According to South China Morning Post, images of the protests posted on WeChat by users in Hong Kong are not visible to recipients in mainland China. Posts on Sina Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, are also allegedly being censored.

And in June, the BBC reported that WeChat users who discussed the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations were blocked from the platform unless they scanned their face.

By contrast, Bridgefy’s Bluetooth underpinnings makes it far harder for the local authorities to keep track of protesters, as the app dodges the Wi-Fi networks that are supposedly monitored by the government.

Is Bridgefy really hidden from the authorities?

In a word, no. Although authorities will find it more difficult to track users, Bridgefy isn’t totally protected from the local government’s surveillance systems.

Speaking to the BBC, Professor Alan Woodward, a computer security expert at the University of Surrey, said: “With any peer-to-peer network, if you have the know-how, you can sit at central points of it and monitor which device is talking to which device and this metadata can tell you who is involved in chats.

“And, of course, anyone can join the mesh [local network] and it uses Bluetooth, which is not the most secure protocol. The authorities might not be able to listen in quite so easily but I suspect that they will have the means of doing it.”

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question A trial will determine whether Meta and YouTube designed addictive products

-

Is social media over?

Is social media over?Today’s Big Question We may look back on 2025 as the moment social media jumped the shark

-

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effect

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effectSpeed Read Kids under age 16 are now barred from platforms including YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and Reddit

-

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTok

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTokSpeed Read Under the deal, U.S. companies would own about 80% of the company

-

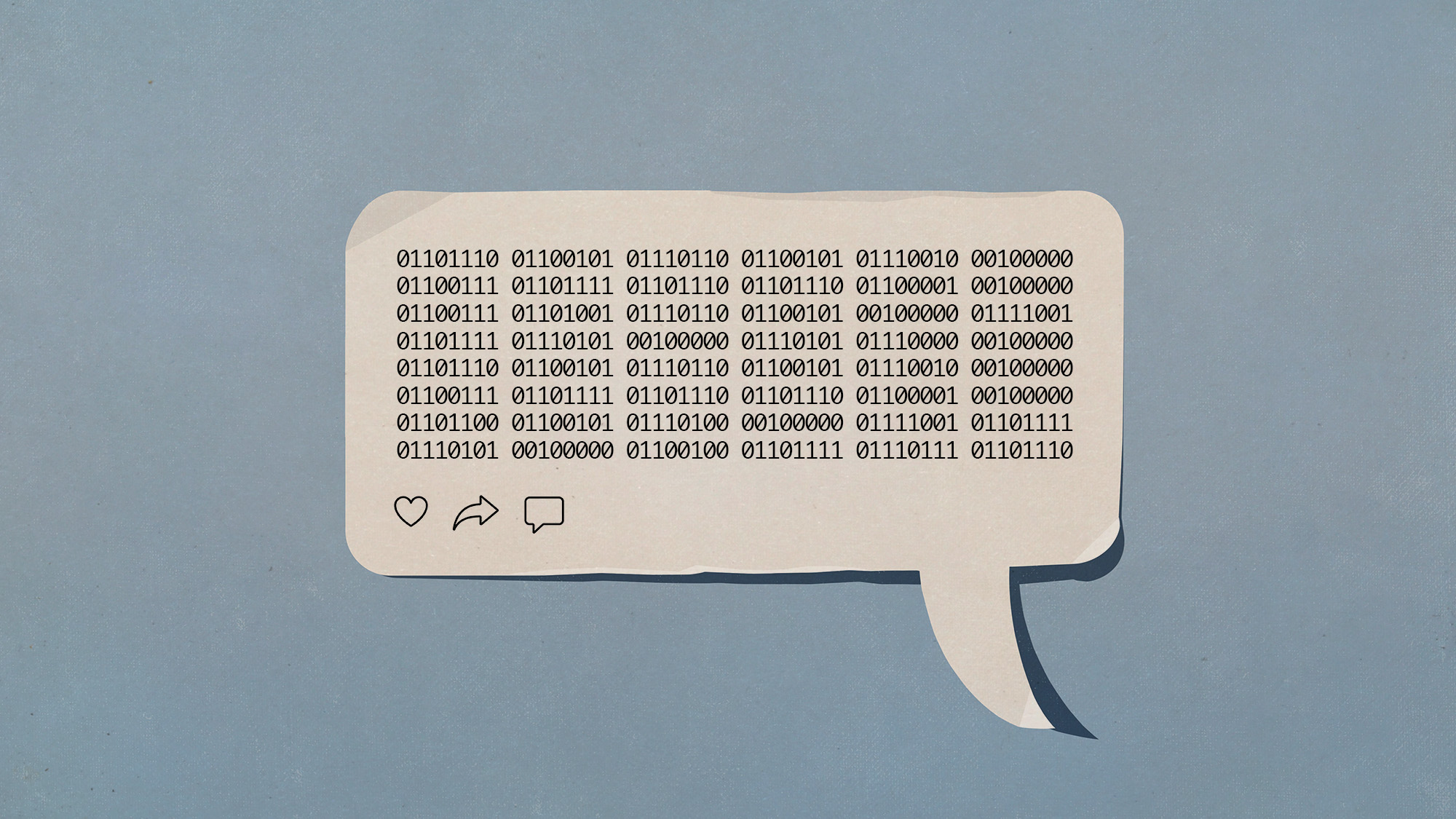

What an all-bot social network tells us about social media

What an all-bot social network tells us about social mediaUnder The Radar The experiment's findings 'didn't speak well of us'

-

Broken brains: The social price of digital life

Broken brains: The social price of digital lifeFeature A new study shows that smartphones and streaming services may be fueling a sharp decline in responsibility and reliability in adults

-

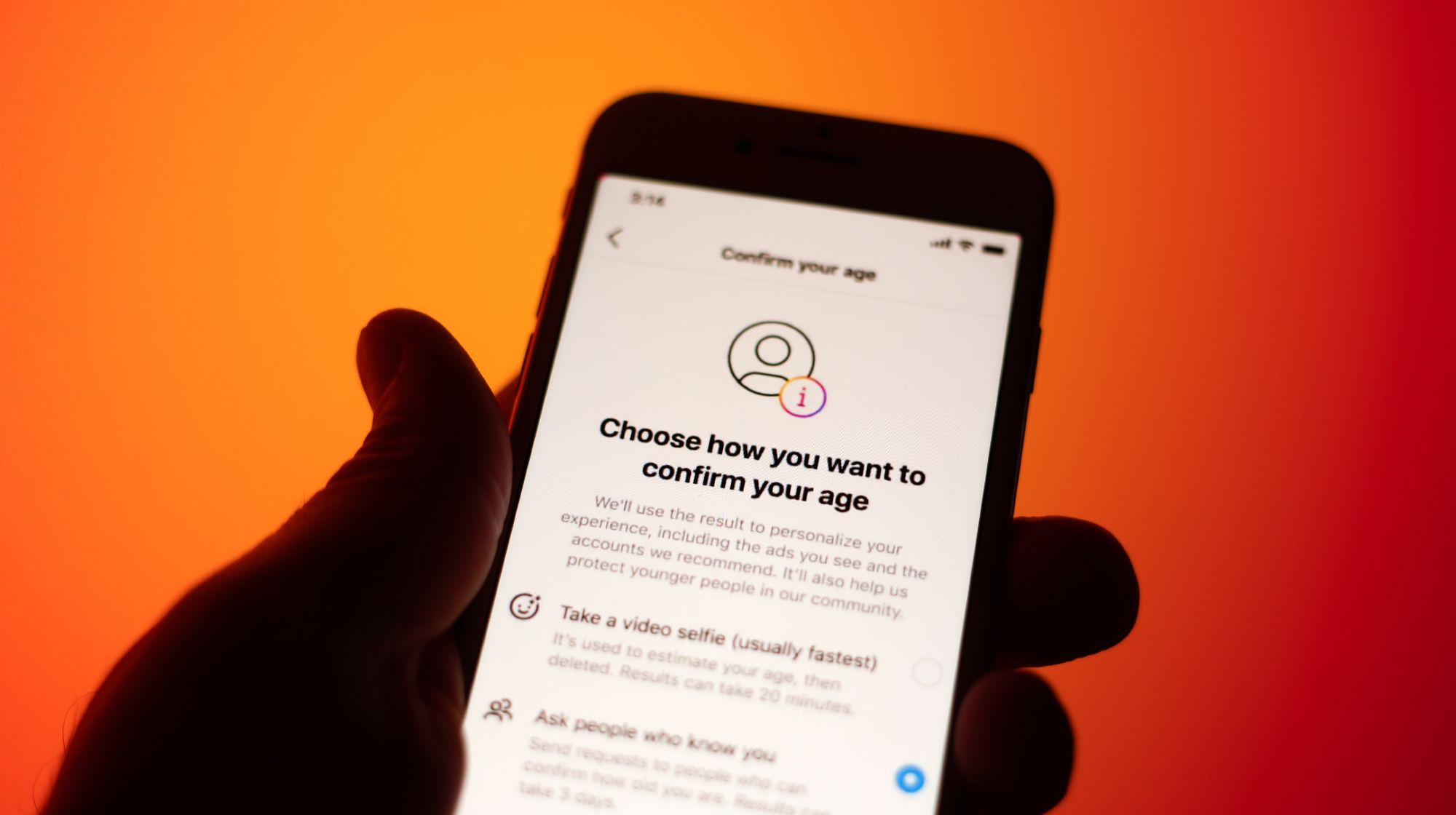

Supreme Court allows social media age check law

Supreme Court allows social media age check lawSpeed Read The court refused to intervene in a decision that affirmed a Mississippi law requiring social media users to verify their ages