9 recent scientific breakthroughs and discoveries

From life-changing cures to species preservation

Harold Maass, The Week US

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Scientists are making new discoveries every day, but many of them fall under the radar. Some of these findings are life-changing, while others expand our knowledge of the world around us. Here are nine recent findings that are making waves.

1. Night-vision contact lenses

Scientists have created contact lenses that can give people super-vision, according to a study published in the journal Cell. The lenses allow "people to see beyond the visible light range, picking up flickers of infrared light even in the dark — or with their eyes closed," said New Scientist. They could potentially be a replacement for night-vision goggles.

"There are many potential applications right away for this material," Tian Xue, a neuroscientist at the University of Science and Technology of China and a senior author of the study, said in a statement. "For example, flickering infrared light could be used to transmit information in security, rescue, encryption or anti-counterfeiting settings." The lenses also do not require a power source like traditional goggles, making them a more usable alternative.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

👩🏽🔬 Science quiz

2. Curing sickle cell anemia

Gene therapy has allowed a 21-year-old man from New York to be cured of sickle cell anemia. The disease is genetic and caused by "inheriting defective copies of a hemoglobin gene, causing hemoglobin, which carries oxygen in red blood cells, to be sub-functional," said Forbes. It is most common in Black and Hispanic people. The therapy is called Lyfgenia, and it uses a person's own "bone marrow in IV transfusions to create normal red blood cells," said CBS News.

"The cliche 'the future is here' is actually true in this case," Charles Schleien, a doctor at Cohen Children's Medical Center, said to CBS News. Lyfgenia was FDA-approved in 2023 but costs $3.1 million per treatment, which could make access to the treatment difficult.

3. Pancreatic cancer vaccine

An mRNA vaccine has shown promise in a trial in patients with pancreatic cancer. "The vaccine can stimulate a long-term immune response that reduces the risk of cancer recurrence after surgery," said Forbes. The findings were published in the journal Nature. While the trial was conducted with only 16 patients and results should be looked at with caution, 8 people responded positively to the treatment.

The vaccine works by "targeting genetic mutations found in pancreatic cancer" and "alerting the immune system to recognize and attack the tumor," said Medical Express. This leads to the production of cancer-fighting T-cells. Whether or not the T-cells will last and extend a person's life requires further study to confirm. "Although we have made significant progress in improving outcomes in many of the other cancers with newer waves of cancer treatments, these have not had much of an impact in pancreatic cancer," Dr. Vinod Balachandran, the director of the Olayan Center for Cancer Vaccines, who led the trial, said to NBC News.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

4. Growing a spine

Scientists have found a way to grow a backbone — literally — according to a study published in the journal Nature. Researchers were able to "coax human stem cells to develop into the 'notochord,' which plays a critical role in organizing tissue in developing human embryos and later becomes the intervertebral discs of the spinal column," said Cosmos Magazine. Specifically, the notochord acts as a "GPS" for an embryo's nervous system, said James Briscoe, the senior author of the study, in a statement.

"What's particularly exciting is that the notochord in our lab-grown structures appears to function similarly to how it would in a developing embryo," Tiago Rito, the first author of the study, said in the statement. "It sends out chemical signals that help organize surrounding tissue, just as it would during typical development." The findings could help further research into how birth defects affect the spine or spinal cord. "It could also be valuable for studying intervertebral discs — the shock-absorbing cushions located between your vertebrate that actually forms from the notochord itself," said Popular Mechanics.

5. Designing a sunlight reactor

Scientists have created a prototype reactor that can harvest hydrogen fuel using only sunlight and water. Green hydrogen, a "climate-neutral process that uses renewable energy sources to create hydrogen," has been a "growing conversation among renewable fuel experts," said Popular Mechanics. However, "only .1% of all hydrogen production can be described as 'green,'" because it "requires so much renewable energy to create, making the process cost prohibitive."

A paper published in the journal Frontiers in Science details a reactor built with photocatalytic sheets that can split water into its elements (hydrogen and oxygen) using the power of the sun. "Obviously, solar energy conversion technology cannot operate at night or in bad weather, but by storing the energy of sunlight as the chemical energy of fuel materials, it is possible to use the energy anytime and anywhere," said Popular Mechanics. However, the product is still in its infancy. "The most important aspect to develop is the efficiency of solar-to-chemical energy conversion by photocatalysts," a senior author of the paper, Kazunari Domen, said in a statement. "If it is improved to a practical level, many researchers will work seriously on the development of mass production technology and gas separation processes, as well as large-scale plant construction."

6. Panda stem cells

Although giant pandas are no longer considered endangered, they are still a vulnerable species. The good news is that scientists may have found a way to support their survival by taking giant panda skin cells and transforming them into stem cells, according to a study published in the journal Science Advances. The stem cells can then be "nudged into becoming any kind of cell in the body" and "could help researchers breed more giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and develop treatments for their diseases," said Science News.

Stem cells are a "self-renewing, inexhaustible source of material from endangered species, capable of regenerating various cell types as needed," and they "could serve as a crucial tool in preventing species extinction," said the study. Successfully creating the stem cells was a difficult process because researchers have to go "back to the basics" for every animal — and "what worked on humans and mice did not work for pandas," Pierre Comizzoli, a gamete biologist at the Smithsonian's National Zoo, said to The Scientist. While it will still be a while before we see a lab-grown giant panda, scientists want to use the cells to create panda embryos.

7. Monkey communication

Marmoset monkeys use names to refer to each other, according to a study published in the journal Science. Scientists "recorded spontaneous 'phee-call' dialogues between pairs of marmoset monkeys," said the study. "We discovered that marmosets use these calls to vocally label their conspecifics. Moreover, they respond more consistently and correctly to calls that are specifically directed at them." This type of behavior had only been seen in humans, elephants and dolphins previously. "This is the first time that we have seen this in non-human primates," David Omer, the lead author of the study, said to CNN.

The study raises questions as to whether this form of communication is rare or if it has simply not been researched enough. "I think that as we refine our paradigms and our techniques of acoustic analysis, we will find that many other social animals have more complexity in their communication systems than we currently realize," Con Slobodchikoff, a professor emeritus of biology at Northern Arizona University, said to The Washington Post. "This paper is a good nudge toward us changing our views about animal capabilities and intelligence."

8. Finding the root cause of lupus

Scientists have discovered a cause of lupus and a possible way to reverse it. A study published in the journal Nature points to abnormalities in the immune system of lupus patients that is caused by a molecular abnormality. "What we found was this fundamental imbalance in the types of T cells that patients with lupus make," Deepak Rao, one of the study authors, said to NBC News. Specifically, "people with lupus have too much of a particular T cell associated with damage in healthy cells and too little of another T cell associated with repair," NBC News said.

The good news is that this could be reversed. A protein called interferon is mainly to blame for the T-cell imbalance. Too much interferon blocks another protein called the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, which helps regulate how the body responds to bacteria or environmental pollutants. In turn, too many T-cells are produced that attack the body itself. "The study found that giving people with lupus anifrolumab, a drug that blocks interferon, prevented the T-cell imbalance that likely leads to the disease," said NBC News.

9. Rhino IVF

Scientists were able to impregnate a southern white rhino using in-vitro fertilization (IVF). Researchers in Kenya implanted a southern white rhino embryo into another of the same species using the technique in September 2023, resulting in a successful pregnancy. The technique could be used to save the northern white rhino from total extinction. "It's very challenging in such a big animal, in terms of placing an embryo inside the reproductive tract, which is almost 2m inside the animal," Susanne Holtze, a scientist at Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Germany, said to the BBC.

There are two species of white rhinos: northern and southern. The northern white rhino is on the verge of extinction due to poaching, with only two females remaining. Luckily, scientists have sperm preserved from the last male rhino, which could be combined with an egg from the female and implanted into a southern white rhino female to act as a surrogate. Using a white rhino embryo to test the procedure was a "proof of concept" which is a "milestone to allow us to produce northern white rhino calves in the next two, two and a half years," Thomas Hildebrandt, the head of the reproduction management department at the Leibniz Institute, said in a statement.

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

Nasa’s new dark matter map

Nasa’s new dark matter mapUnder the Radar High-resolution images may help scientists understand the ‘gravitational scaffolding into which everything else falls and is built into galaxies’

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

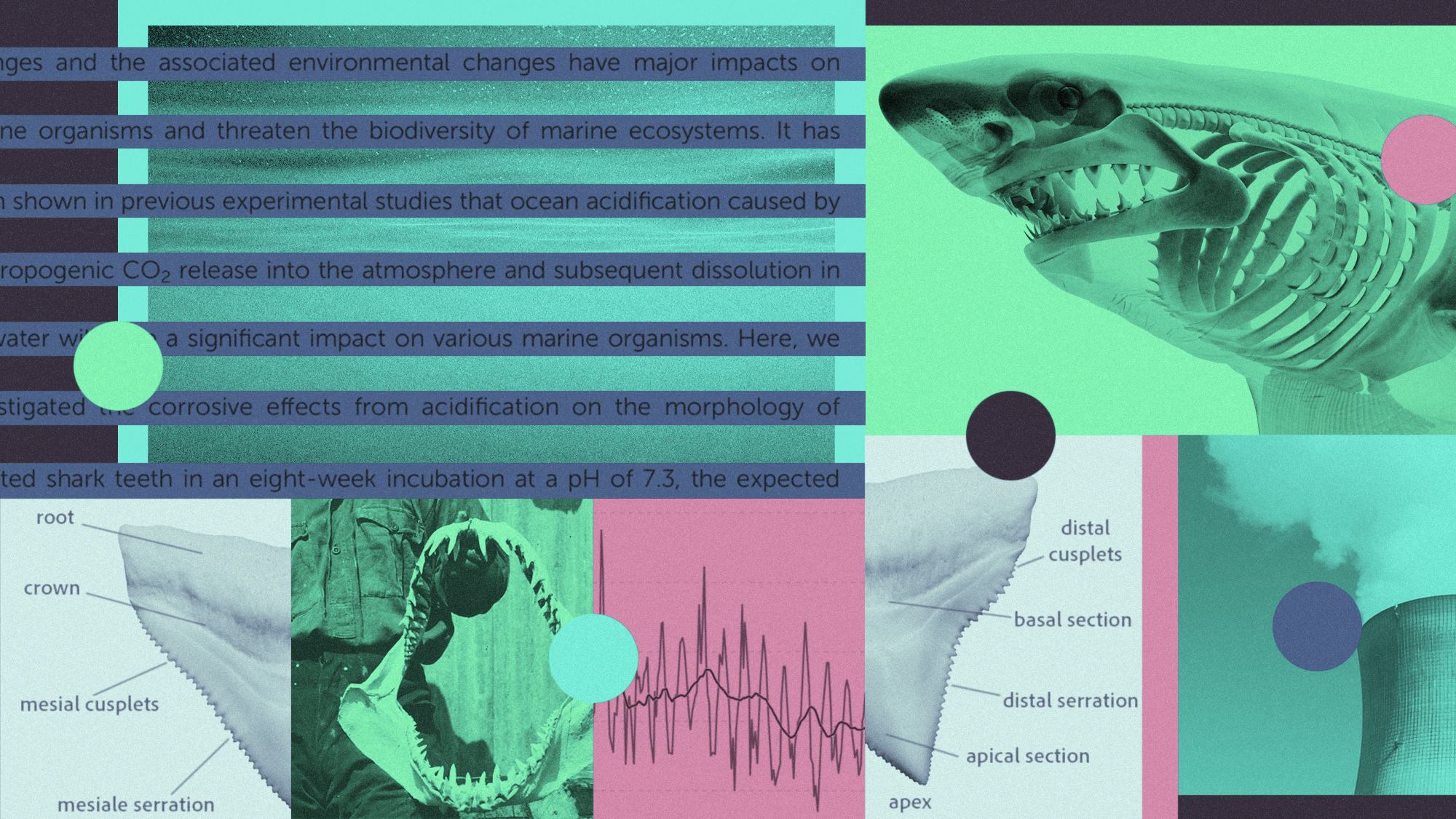

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

How Mars influences Earth’s climate

How Mars influences Earth’s climateThe explainer A pull in the right direction