'Inverse vaccine' shows promise treating MS, other autoimmune diseases

New research effectively cured mice of multiple sclerosis–type symptoms. Could this work in humans?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

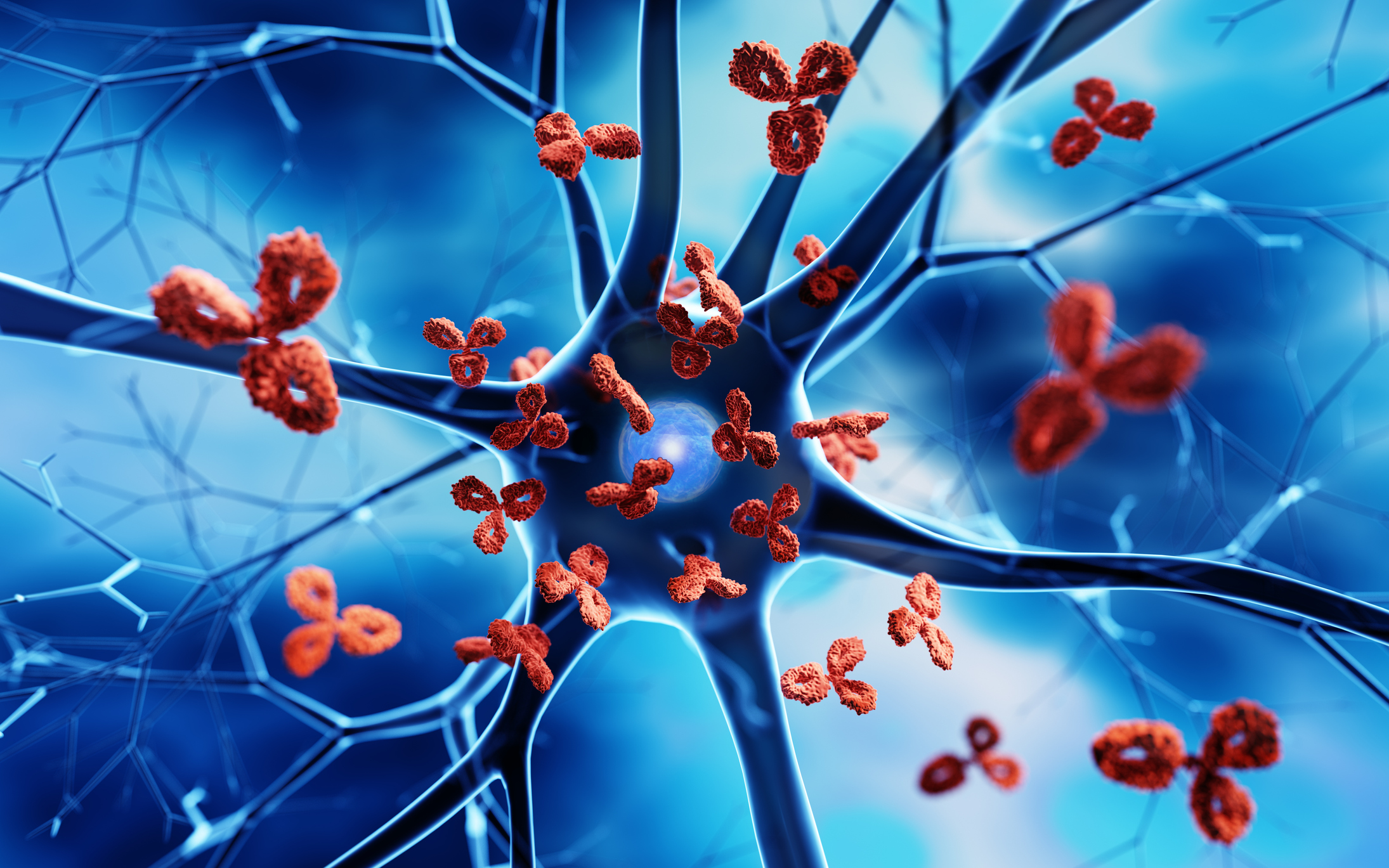

Researchers at the University of Chicago completely reversed a multiple sclerosis–type autoimmune disorder in mice, using a new technique that tricked the liver into neutering a specific immune response, the team reported in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering. Current treatments for autoimmune diseases suppress the entire immune system, making patients more susceptible to infections.

A body's protective T cells attack antigens, or molecules and molecule fragments, usually harmful viruses or bacteria. But with autoimmune diseases, the T cells attack a body's own healthy molecules, called self-antigens, Science explained. The University of Chicago team found that by attaching a sugar protein, N-acetylgalactosamine (pGal), to the self-antigen under assault, they could send it to the liver, which would teach the immune system to tolerate the molecule.

"Rather than rev up immunity as with a vaccine, we can tamp it down in a very specific way with an inverse vaccine," lead author Jeffrey Hubbell said in a statement. The hope is that these "inverse vaccines" will prove effective at treating MS, lupus, Type I diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis and other befuddling autoimmune disorders. A company Hubbell co-founded recently completed a phase 1 trial using this technique on people with celiac disease and has started a phase 2 trial.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists not involved in the research said the findings are promising but cautioned that previous methods for calming a body's immune response to self-antigens had come up short when moving from animal testing to human trials.

The paper is "a strong piece of work," introducing "a cool new way" to teach the body's defenses to stop attacking healthy tissue, Stanford Medicine neuroimmunologist Lawrence Steinman told Science. Whether this approach ultimately proves effective in humans, he added, "I hope that someday somebody is going to get it right and change the world."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

A potentially mutating bat virus has some scientists worried about the next pandemic

A potentially mutating bat virus has some scientists worried about the next pandemicUnder the Radar One subgroup of bat merbecovirus has scientists concerned

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature