Madagascar plague: Middle Ages’ disease now a modern killer

Nine other African countries on high alert after more than 200 deaths in island nation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A sudden and rapid outbreak of plague in the past few months has led to more than 200 deaths and at least 2,348 suspected and confirmed cases on the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar.

Although the outbreak in Madagascar, off Africa’s southeastern coast, appears to be slowing down, its severity and speed has raised fears about the likelihood of the disease claiming more lives. Nine other countries and overseas territories in the African region remain on high alert, the World Health Organization reports.

Across the globe, plague “flare-ups cause public health emergencies on an almost annual basis”, according to Vox. The Democratic Republic of Congo, Peru and India regularly report cases, and the disease has also been seen in the US, in dry southwestern states including Arizona, California, New Mexico and Colorado. The US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says there were 16 plague cases reported nationwide, resulting in four deaths, in 2015.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“You get rodent populations that still carry the disease,” Don Walker, a bone specialist at the Museum of London Archaeology who studies the DNA of skeletons of Black Death victims, told Al Jazeera. “And occasionally, there might be someone out there who gets too close and can get infected.”

But how much of a threat does plague really pose to the modern world and who is most at risk?

The history of plague

Plague is caused by a bacterium known as Yersinia pestis, and is life threatening if not treated quickly, says the Harvard Health Publishing website. The disease primarily affects rodents such as rats, mice, squirrels, prairie dogs, chipmunks and rabbits. The CDC says it is most commonly transmitted to humans when they are bitten by a flea infected with plague bacteria.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are three forms of plague. Bubonic is the most common, accounting for more than 80% of all reported cases in the US. Painful, dark swellings known as buboes usually appear near the site of an infected bite, followed by a fever, chills, muscle aches, headache and extreme weakness. Without proper treatment, the carrier may develop septicemic plague.

Septicemic plague, the second-most common form of the disease, is the infection of a carrier’s blood. Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain, along with internal bleeding. However, with appropriate treatment, 75% to 80% of sufferers survive, the Harvard website says.

Pneumonic plague is the deadliest form, developing when Yersinia pestis infects the lungs. Without proper treatment, pneumonic plague can quickly lead to death.

Although Yersinia pestis was not officially documented as the cause of plague until 1894, it is believed to have caused devastating pandemics dating back as far as AD541, the CDC says. The most significant outbreak was the Black Death in the mid-14th century, which is estimated to have killed between 75 million and 200 million people - including 30% to 60% of Europe’s entire population - in just a few years.

Current risk

Plague has become a relatively rare disease, as all forms can be treated with antibiotics, but there are still thousands of cases each year.

Countries in Africa, South America and Asia regularly suffer minor outbreaks, with Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Peru and India most frequently hit.

The Democratic Republic of Congo alone recorded more than 10,000 cases between 2000 and 2009, according to a study by the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. In the same period, 57 cases of plague were reported in the US, with seven deaths.

Most of the US cases were believed to have originated in rock squirrels and ground squirrels, two species in which plague has become endemic in America.

Why can’t we beat a medieval disease?

“The tragedy in most cases is that people don’t realise what they have and think they have the flu,” Sharon Collinge, professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, told CNN.

Financial considerations may also stop many people from seeking treatment.

“For some people, it costs money to seek healthcare and if you don’t believe that you have a severe disease, maybe you’ll say, “Why am I gonna spend money to go seek healthcare when I’m sure I’ll get better soon”, and just wait it out,” virologist Daniel Bausch told NPR. “Because in the beginning, the plague doesn’t seem that different from a cold or other respiratory disease.”

“And there still can be a stigma - people don’t want to be recognized as having the disease,” Bausch adds.

Ultimately, Collinge concludes, plague is “like a lot of pathogens”, insofar as “it’s persistent and emerges at certain times and places for reasons that still remain somewhat mysterious”.

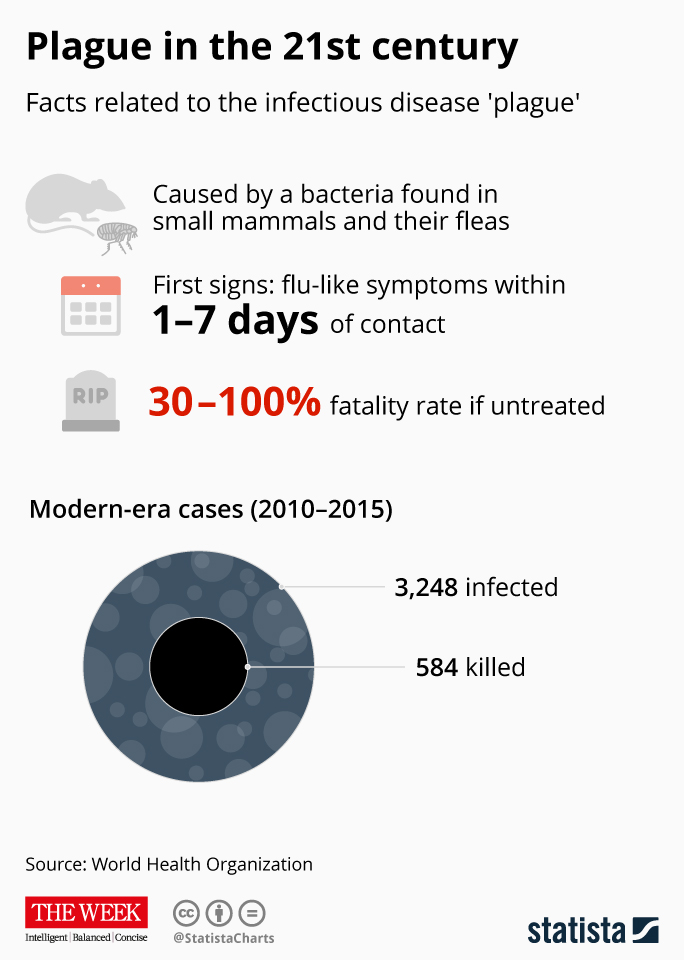

Infographic by www.statista.com/chartoftheday for TheWeek.co.uk

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military