Fighting inflation could flatten the economy — and Joe Biden

We might be about to revisit 1982

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Inflation has been in the news a lot over the past six months, and for good reason. With the Consumer Price Index in February showing an increase of 7.9 percent over the past year, the fastest pace of inflation in 40 years, Americans have reason to worry — and not only because of the pain inflicted by rising prices themselves.

Forty years ago was 1982. The CPI was high then, but it was heading down sharply from a peak of 14.6 percent in April 1980. What brought inflation under control was the decision of Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker (nominated by President Jimmy Carter in the summer of 1979) to raise interest rates so sharply that the American economy was plunged into the most painful recession since the Great Depression, with unemployment hitting a peak of 10.8 percent in November and December of 1982.

That brought an era of high inflation to an end, but at the price of throwing millions of Americans out of work. If it becomes necessary for our own Fed chair, Jerome Powell, to do something similar today, the economic repercussions could be severe — and the political consequences (above all for President Biden) ominous.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The inflationary pressures of the moment have several sources. At the most basic level, underlying trends in the global economy may be encouraging higher prices.

Right at the start of the pandemic, long before inflation kicked in, former U.K. central banker Charles Goodhart predicted a future with markedly higher rates of inflation than prevailed over the previous decade. The reason? An era of inexpensive labor (with attendant low wages and prices) was giving way to one characterized by worker shortages (and hence higher prices) driven by declines in birthrates and the working-age population across the developed world. According to a recent profile in The Wall Street Journal, this led Goodhart to predict that "fiscal stimulus and the post-pandemic recovery" would lead inflation to reach "between 5 percent and 10 percent in 2021 — and stay high."

He was right. Pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions across the globe have helped to produce a 5.8 percent inflation rate in the eurozone and the significantly higher numbers we're seeing in the United States (where the government spent considerably more money, in three large relief packages, to soften the blow of pandemic disruptions).

But that's not all. The massive economic sanctions imposed on Russia over the past three weeks in retaliation for its invasion of Ukraine have led to additional price spikes across a range of commodities, including oil, gas, and wheat. The increase is already obvious at the pump and the grocery store, with secondary effects likely to be felt throughout the economy, with the threat of stagflation (declining growth coupled with rising prices) a real possibility for the first time since the Carter administration.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Finally, in response to the first large surge in COVID-19 cases since the initial wave of the pandemic, China has imposed a lockdown on Shenzhen (a city of 17 million), with Shanghai (at 25 million residents, the most populous city in the world and a global financial hub) facing travel restrictions and a possible lockdown of its own. (Similar draconian measures could be imposed across China over the coming days and weeks.)

The prospect of China downshifting economically once again in response to the pandemic has helped to lower oil prices over the last few days. But its somewhat longer-term effect on global supply chains points in the opposite direction — toward the kinds of widespread disruptions that, when combined with strong stimulus-driven consumer demand, triggered the initial price increases of 2021.

Put it all together and we're left with ample reason to expect our already elevated prices will be heading even higher over the coming months.

In response, Powell has made clear he intends to raise interest rates several times this year, perhaps beginning with a quarter-point hike as soon as this Wednesday. Traders expect at least three more increases in 2022, bringing the funds rate to around 1 percent from its current range of close to zero.

Will that be enough to bring inflation under control? It's hard to say. When Volcker began administering shock treatment to the American economy in the fall of 1979, interest rates were already high — 11 percent. Volcker sent them much higher — up to as high as 20 percent on several occasions throughout 1980 and '81. The result was two recessions — the first from January to July 1980, and a second, more severe one from July 1981 to November 1982.

By the time it was over, inflation had been tamed and the American economy was poised for a decade of strong growth.

With interest rates at historic lows today, precisely how high Powell would have to raise them to conquer inflation is far from clear. But raising them to around 1 percent by the end of the year — a plan first hatched months ago, when the Fed chair was still describing present-day inflation as "transitory" — is unlikely to do the trick.

And that leaves us with a series of wrenching questions: If setting a funds rate at 1 percent is inadequate, how high will be high enough? Does the Fed chair need to deploy all the monetary firepower that Volcker brought to bear against inflation 40 years ago? Will it be necessary, in other words, to plunge the economy into a deep and painful recession? And what would be the political consequences of such an economically traumatizing move?

Carter's loss to Reagan in 1980 was overdetermined — with the interminable Iranian hostage crisis, double-digit inflation, surging interest rates, and the recession that struck during the winter and spring of a presidential-election year all playing important roles in the incumbent's defeat. Two years later, in the midst of the 1982 recession, Reagan's approval rating was languishing in the low 40s, exactly where Biden finds himself today; if Reagan had been up for re-election that year, he would have been as vulnerable as Biden feels right now. Instead, the recession ended and soon it was "Morning in America," with Reagan winning a second term and carrying 49 states in a landslide.

This year — 2022 — is Biden's 1982, the second year of his first term, two years out from a re-election campaign. The problem is the timing of the Fed's shock therapy. Where Volcker began to raise interest rates before the 1980 election, Powell hasn't even begun to do so. If he moves swiftly now, it could guarantee a bloodbath for Democrats in the midterm elections later this year. There would also be no guarantee the country will have emerged from recession in time for the presidential election of 2024.

But if Powell hesitates to act, that could ensure Biden's approval rating remains soft over the coming months as inflation and even stagflation settle in. That scenario could also set up a sharp hike in interest rates much closer to 2024, which could have the president fighting for re-election while the country is in the grips of a painful economic slump.

The politics of inflation is never easy. But Biden and his party may soon be facing an uncommonly grave political situation — one in which the best option is bad and the next best is downright terrible.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Touring the vineyards of southern Bolivia

Touring the vineyards of southern BoliviaThe Week Recommends Strongly reminiscent of Andalusia, these vineyards cut deep into the country’s southwest

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Elon Musk’s starry mega-merger

Elon Musk’s starry mega-mergerTalking Point SpaceX founder is promising investors a rocket trip to the future – and a sprawling conglomerate to boot

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

‘They’re nervous about playing the game’

‘They’re nervous about playing the game’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugees

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugeesSpeed Read The memo also ordered all green card applications for the refugees to be halted

-

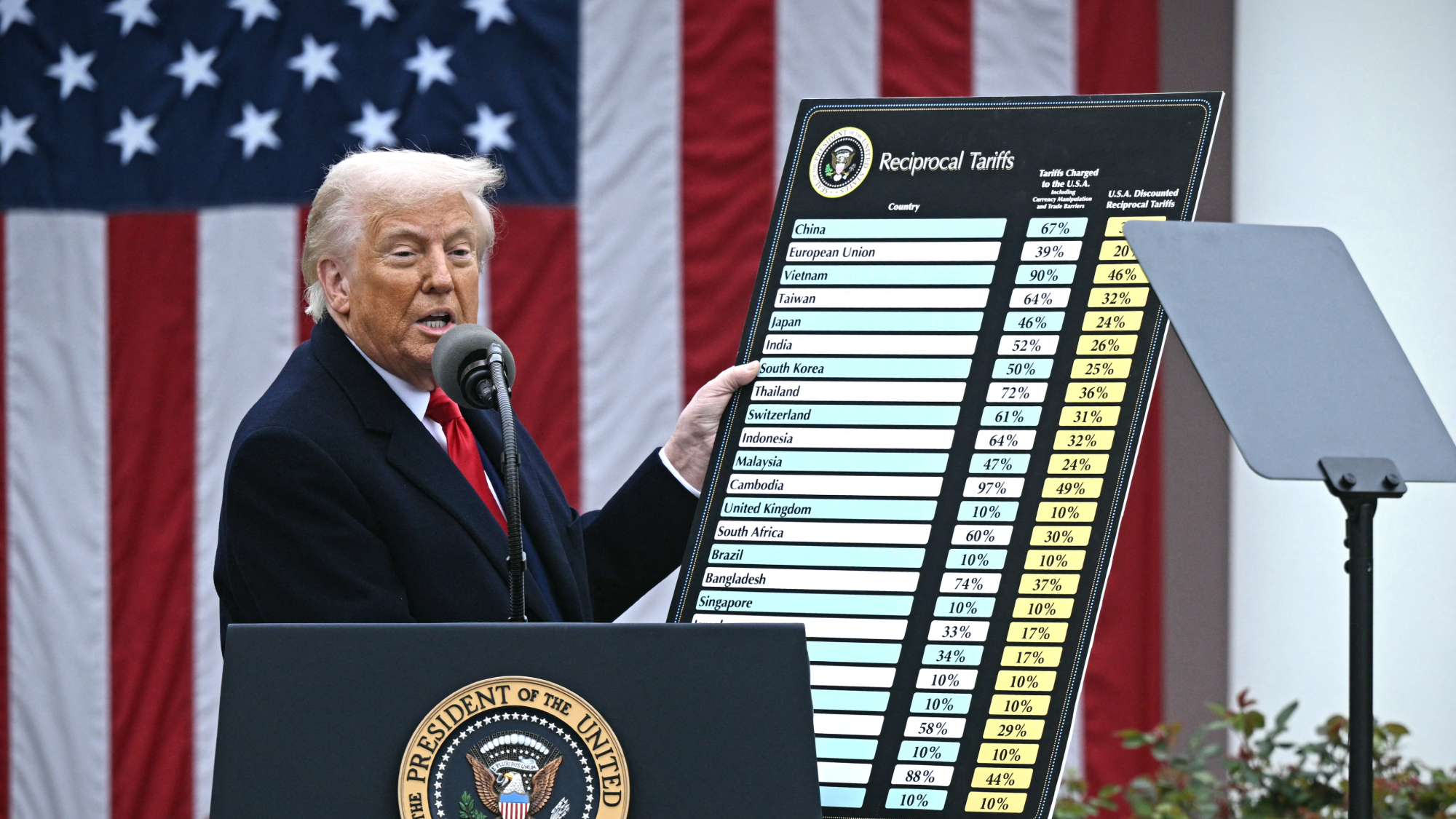

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?

Tariffs: Will Trump’s reversal lower prices?Feature Retailers may not pass on the savings from tariff reductions to consumers

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June