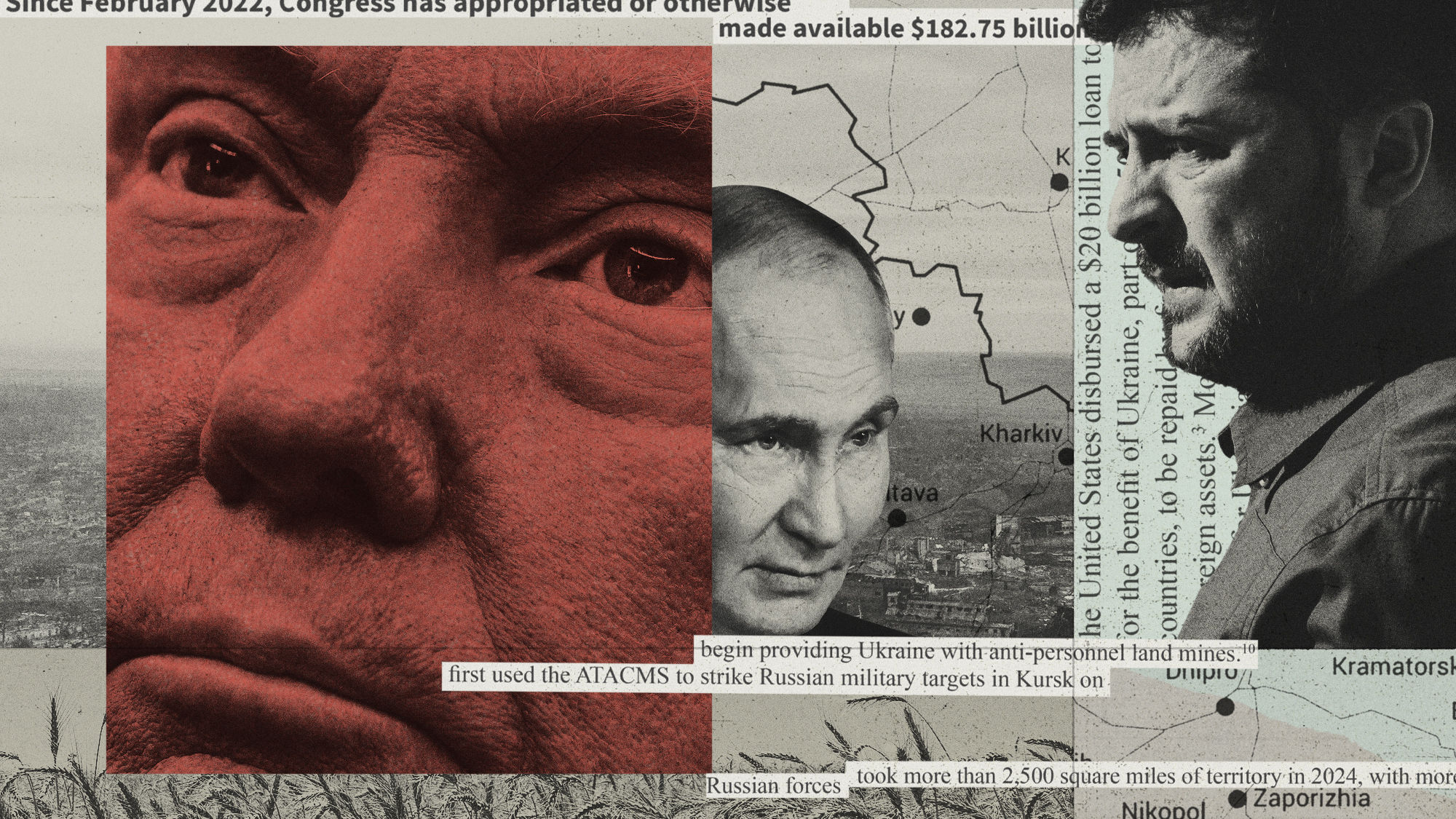

How Russia lost its footing in the propaganda war against Ukraine

Nazis, cats, and Russia and Ukraine's fierce information war

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Russian President Vladimir Putin gave the order to invade Ukraine, most analysts expected a quick conquest by Russia's vastly superior military forces. That didn't happen on the ground. Equally surprising, "Ukraine is winning the information war, hands down," Graham Shellenberger, a propaganda expert at Miburo Solutions consultancy, told Fox News.

The information war — or propaganda war — has been especially important in shaping how dramatically Ukraine and the world have responded to Russia's invasion. Russia has been sharpening its disinformation skills at least since the Bolsheviks seized control in 1917. Under Putin — a former intelligence officer — the Kremlin has fostered effective, widely feared cyber-ops capabilities.

Nevertheless, "Russian propaganda is tanking, but Ukraine has been hitting home runs for a week now," writes Ian Garner, a Russia historian who has followed Russian-language propaganda during the conflict. Every day "I'm more convinced than before that Putin's regime has totally overestimated its ability to win a propaganda war."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How is Russia trying to sell its invasion?

Essentially, Nazis and NATO. Ever since Russia seized Crimea and backed separatist enclaves in the Donbas region in 2014, Putin has claimed that Ukraine is led by a Western puppet government of Nazis committing "genocide" against Russian-speaking Ukrainians. When he announced his "special military operation," Putin said the goal was the "demilitarization and de-Nazification of Ukraine."

"The Kremlin's other propaganda message was that Ukraine posed an existential threat to Russia, that they needed to create a buffer between NATO (a proxy for the U.S.) and the EU," writes Politico's Zoya Sheftalovich. Putin has spent the past 22 years trying to prevent Ukraine from aligning with Western Europe and pulling out of Russia's sphere of influence.

To drive that point home, The Wall Street Journal notes, "Russian officials and propagandists have for years boasted that Moscow's forces could overrun its smaller neighbor in days."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What is Ukraine's message?

If Russia is trying to sell the idea of liberating Ukraine from mythical Nazis, Ukraine is comparing Putin's invasion to Adolf Hitler's massacres of Ukrainians in World War II. But more than anything, "Ukraine's online propaganda is largely focused on its heroes and martyrs, characters who help dramatize tales of Ukrainian fortitude and Russian aggression," The New York Times reports.

"If Ukraine had no messages of the righteousness of its cause, the popularity of its cause, the valor of its heroes, the suffering of its populace, then it would lose," Peter Singer, a strategist at the New America think tank, told the Times. "Not just the information war, but it would lose the overall war."

Kyiv is pushing out stories of Ukrainian heroes and martyrs, Russian brutality against civilians, and civil resistance, Singer writes. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has "set the new standard" as a "Man of the People," winning over both Ukrainians and foreign leaders by communicating from the streets and bunkers of the besieged capital. And the Ukrainians have been very effective at "humanizing" the war, he adds. "This is where the cat is the most lethal weapon of information warfare."

Cats? Seriously?

Yes.

This may be one reason the International Cat Federation banned Russian cats from competition.

Why is Ukraine's propaganda campaign winning?

For one thing, it is easier to sell the story that Russia is the murderous aggressor — it objectively invaded Ukraine and is killing civilians, after all — than the notion that Ukraine or NATO or a Jewish Nazi president forced Putin to invade. Ukraine, the U.S., and some NATO allies also effectively "pre-bunked" Russia's victim claims by documenting the Kremlin's months-long amassing of troops along Ukraine's border, Singer says.

The Biden administration began sharing intelligence about Russia's movements and motives with often-skeptical allies last fall, then took the extraordinary step of going public with almost real-time intelligence in the weeks leading up to Putin's invasion, Politico reports. "Slowly and painstakingly, reluctant allies were brought on board," and then when Putin pulled the trigger, the West was much more unified and quick with punishing sanctions than Putin — and maybe even the West — expected.

Russia has also hamstrung itself by sticking to its lie about a limited "special military operation." The Ukrainians "are posting evidence of their combat successes," but Russia is not, says Michael Kofman, a military analyst at the CNA think tank. "In a desperate effort to keep the war hidden from the Russian public, framing this as a Donbas operation, Moscow has completely ceded the information environment to Ukraine." Pro-Kremlin state broadcasters are stuck "trying to talk about a war that is apparently not happening," Ian Garner tells the Times.

What other missteps has Russia made?

To a large extent, Russia is fighting the last information war. Western governments and social media companies have spent much of the last decade battling Russian disinformation campaigns, and Russia so far hasn't produced many new tricks.

What we're seeing from Russia is "a stagnant propaganda machine that knows how to create chaos and tear things — especially the West — down," Garner writes. "But it's the propaganda machine of an empire. It's not agile, and it doesn't know how to respond to current events and the strong Ukrainian and Western efforts." Meanwhile, Russians are seeing "their peers and idols" bypass state TV and explain what's going on, in Russia, on social media, he adds.

"Most of Russia's propaganda and disinformation about Ukraine for the last eight years, but certainly in the last couple of months, is focused on the Russian domestic population," Graham Shellenberger tells Fox News. "That is their No. 1 target." But instead of trying to connect with Russians and prepare them for the pain to come, the Kremlin "narrative looks more like WWI — a detached imperial tsar directing his troops in an abstract war against imperial opposition," Garner writes. And not "even the most war-hungry Russians are buying into Putin's WW2 cosplay dreams."

Putin is "old school because he's thinking like it's the 90s, even, where everyone is still watching state TV," CNN correspondent Nic Robertson reports. Older Russians, like Putin, who "grew up in the Soviet Union like him, they are watching it and hearing his message and believing it. They believe that the country was forced to go to war," he said. "But there's a lot of the younger generation that are getting their information by social media" and "from talking to their buddies who live all over Europe and are seeing what we're seeing [is] happening in Ukraine," and they know Putin "is lying to them."

Can Putin win back foreign opinion?

By launching a full-bore invasion for all the world to see, Putin effectively silenced his boosters outside Russia, turning some into outright critics. Even some of Putin's biggest apologists are calling the Ukraine invasion a mistake, and countries and companies have spent the last week jumping on the Russian embargo bandwagon. The people appalled by the violation of Ukraine's sovereignty and Russian violence have, in effect, joined the propaganda war.

"A key to information warfare in the age of social media is to recognize that the audience is both target of and participant in it," Singer told the Times. Social media users are "hopefully" sharing viral messages from Ukraine, "which makes them combatants of a sort as well." Once people are engaged in a war effort, it is hard, though not impossible, to get them to switch sides.

Can Russia turn this around?

Domestically, maybe. The Kremlin just effectively killed the last of Russia's independent media, and the education ministry is mandating that all schoolchildren be given a virtual lesson in "why the liberation mission in Ukraine is a necessity," as well as "how to distinguish the truth from lies in the huge stream of information, photos, and videos that are flooding the internet today." Shifts in public opinion are hard to predict.

The Kremlin will have a hard time convincing Russians that their smaller neighbor poses an existential threat to Russia and "Russian exceptionalism," Politico's Sheftalovich writes. "It's like trying to convince Americans that Canada is going to attack. Or Australians that New Zealand is about to take over." But the argument that Ukraine is a stand-in for NATO and the U.S. "is more powerful, it rings a little truer. And it no doubt helps fighter pilots drop cluster bombs on Kharkiv."

The "bizarre anti-NATO/US imperialism rants" do "move public opinion slowly against the enemy," Garner writes, but so far "state TV political shows, which have good viewing figures, aren't talking about or to people or individuals, who will be the key to winning the propaganda war." And "the longer this goes, the harder it will be for Putin to control what's going on," Shellenberger adds. "It's easier to tell people it's fine until the body bags start coming home."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

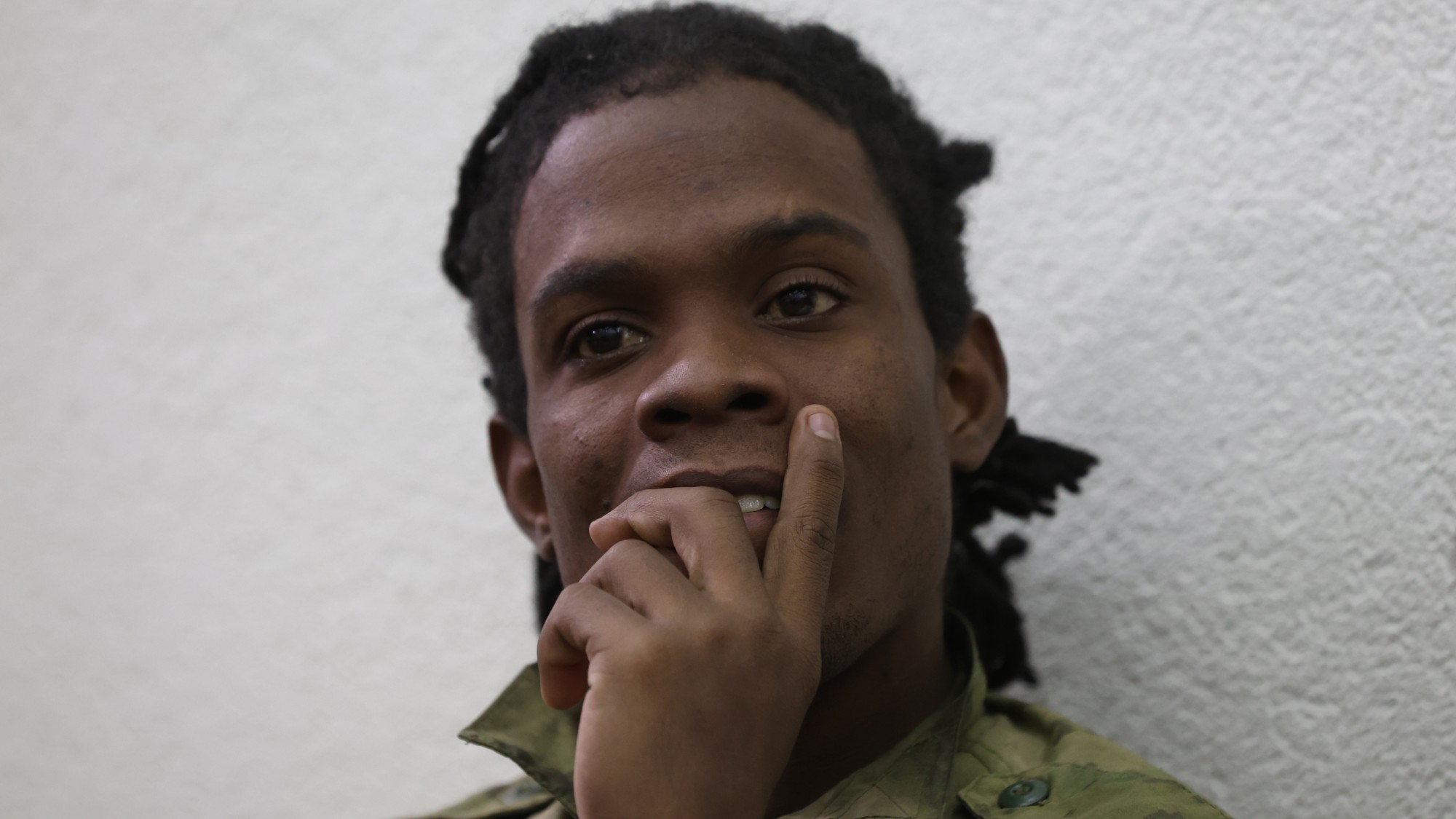

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles