Sarah Everard: why indecent exposure is still not taken seriously

Wayne Couzens kidnapped and murdered the 33-year-old just days after reportedly exposing himself to other women

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Community justice teaching fellow Jennifer Grant of University of Portsmouth on why ‘flashing’ should be treated as more than just a ‘nuisance’ offence

As a child, I was taught to laugh if I stumbled across a man who was indecently exposing himself.

My experiences growing up reflect a wider societal view that indecent exposure is not a serious sexual offence. The older stereotype is of a comical “flasher” in a long overcoat lurking in the bushes. These days, when women go online to try to make meaningful connections, they risk getting an unwanted dick pic. Whether the “flasher” is offline or online, we are encouraged to laugh about it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Women are conditioned by society to see these experiences as funny and the men as pathetic. But it really isn’t something to laugh about. The reality is that these incidents make women feel vulnerable, violated and unsafe. Indecent exposure is therefore a serious issue for women.

It also becomes a serious issue for society if culprits go on to commit contact sexual offences and violence. The Independent Office for Police Conduct is investigating three allegations of indecent exposure made against Wayne Couzens prior to the night he kidnapped and murdered Sarah Everard. Of these, two related to incidents alleged to have taken place just three days before the murder. It appears that these incidents were not taken seriously or formally investigated by police at the time.

In the course of my research, I’ve been reviewing all the available literature on indecent exposure from the last 30 years. I found a tendency to describe indecent exposure as a “nuisance” offence. When the Law Commission was trying to update the legal framework in 2015, its assessment included references to “flashing” - language that implies that legally we still aren’t viewing indecent exposure as a serious and sexual crime.

Indecent exposure was only formally classified as a specifically sexual offence in 2003. Before then, it was legally defined within the Vagrancy Act of 1824. This act suggested the offence was committed by “rogues and vagabonds”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So, up until relatively recently, if you’d been a victim of indecent exposure, you wouldn’t have been seen as a victim of a sexual offence. This is surprising, given that indecent exposure involves the intentional exposure of the genitals. The slow shift in legislation reflects that indecent exposure is only just starting to be taken seriously.

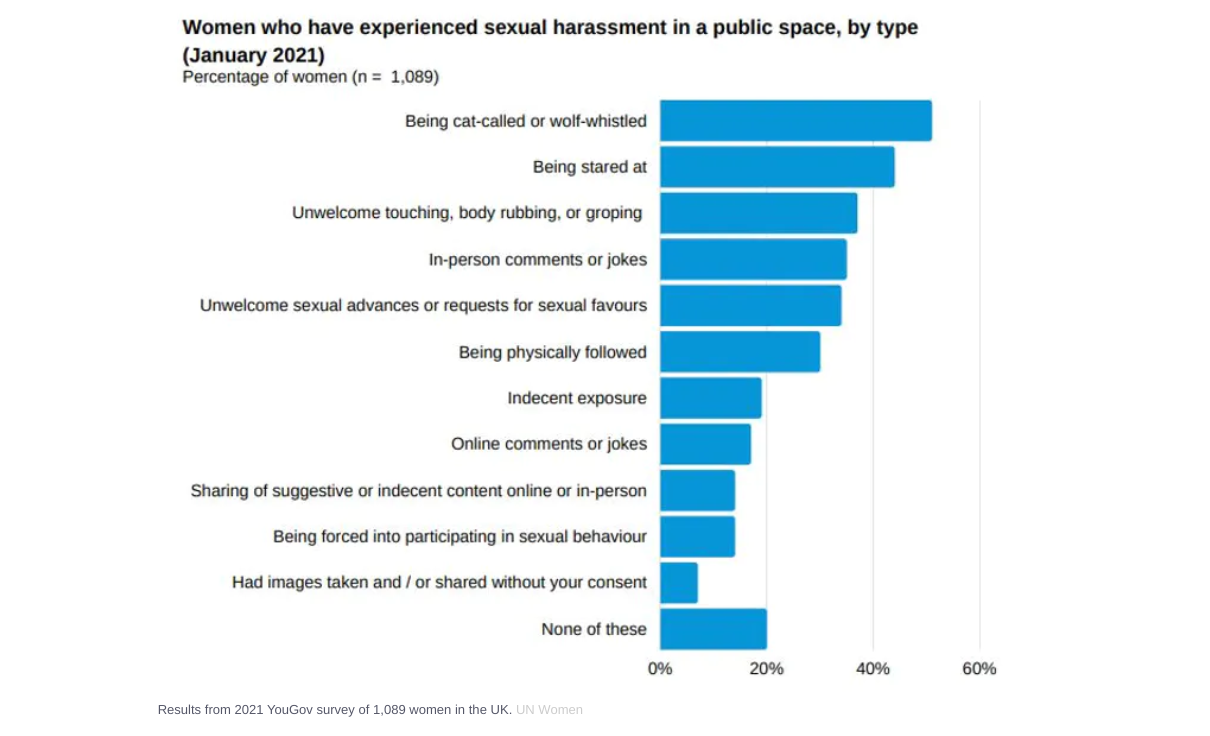

And yet it is a prevalent offence. Although official statistics suggest that indecent exposure is not very common, studies undertaken with victims consistently suggest otherwise. A recent YouGov survey found that almost one in five participants had experienced indecent exposure.

The reality for victims

This contradiction between official statistics and victim studies can be explained by the fact that women simply don’t report the crime. There are various reasons why they might not go to the police. They might be traumatised and unwilling to revisit the experience or they might fear for their future safety after reporting someone.

Crucially, victims might not believe the incident is serious enough to be reported, which wouldn’t be surprising given that we are all taught from an early age that indecent exposure is not a big deal.

There is evidence that some victims do not report indecent exposure because they lack confidence in the system. If society continues to view indecent exposure as a “nuisance” then women will continue to feel reluctant to report their experiences to the police. This means they will carry around the psychological harm and fear that indecent exposure creates in silence.

Re-offending and escalation

Despite under-reporting, the research tells us that men who indecently expose themselves have high rates of re-offending. The largest consolidation of relevant research suggested 25% of men go on to commit further offences of indecent exposure (on average).

These high re-offending rates also include some exhibitionists escalating into other sexual acts. Men who indecently expose themselves can escalate to sexual offending involving physical contact, as appears to have been part of the picture with Couzens.

I do want to be clear: Couzens is not representative of the typical man who indecently exposes himself. But he is a reminder of the worst-case scenario. What happened to Sarah Everard demonstrates why we should take this type of offending more seriously.

When we identify indecent exposure, we do not know exactly who will escalate to commit contact sexual offences. The current research base does not agree on how and why this escalation occurs. Men who indecently expose themselves are a varied group with a wide range of motivations. This lack of clear evidence makes the punishment and rehabilitation of men who indecently expose themselves more difficult. However, it does not detract from the need for indecent exposure to be properly investigated, punished and treated.

And as long as victims remain reluctant to report this type of offence to the police, we cannot get an accurate picture of how regularly indecent exposure occurs. Ultimately, society as a whole does not take indecent exposure seriously. This is in spite of the significant psychological impact it has on victims - and the potential for offenders to go on to commit other crimes. Perhaps it is time to stop laughing.

Jennifer Grant, teaching fellow, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Portsmouth.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

Ex-Illinois deputy gets 20 years for Massey murder

Ex-Illinois deputy gets 20 years for Massey murderSpeed Read Sean Grayson was sentenced for the 2024 killing of Sonya Massey

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

Australian woman found guilty of mushroom murders

Australian woman found guilty of mushroom murdersspeed read Erin Patterson murdered three of her ex-husband's relatives by serving them toxic death cap mushrooms

-

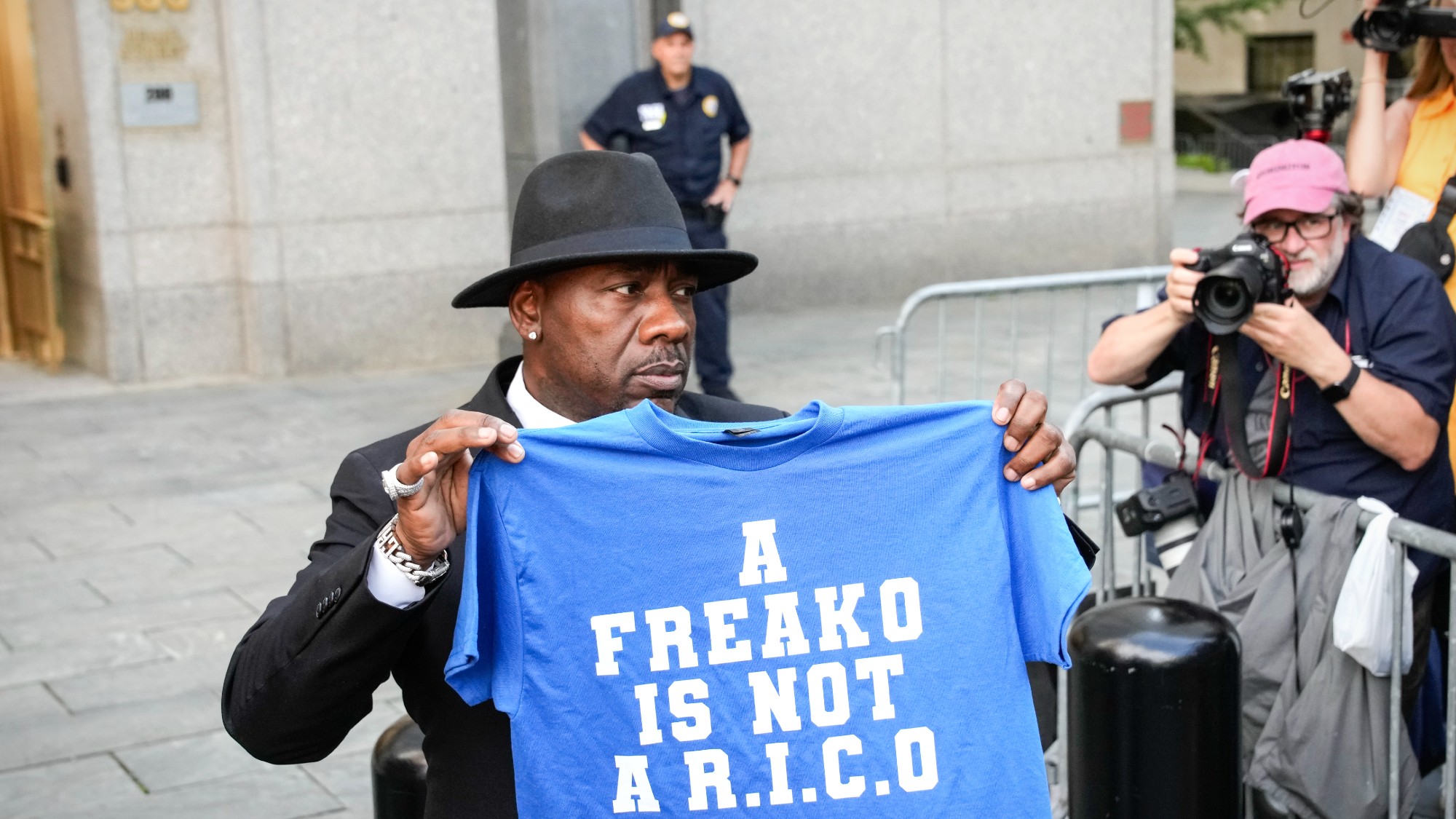

Combs convicted on 2 of 5 charges, denied bail

Combs convicted on 2 of 5 charges, denied bailSpeed Read Sean 'Diddy' Combs was acquitted of the more serious charges of racketeering and sex trafficking

-

Crime: Why murder rates are plummeting

Crime: Why murder rates are plummetingFeature Despite public fears, murder rates have dropped nationwide for the third year in a row

-

Weinstein convicted of sex crime in retrial

Weinstein convicted of sex crime in retrialSpeed Read The New York jury delivered a mixed and partial verdict at the disgraced Hollywood producer's retrial

-

The missed opportunities to save Sara Sharif

The missed opportunities to save Sara SharifTalking Point After each horrific child abuse case, we hear that lessons will be learnt. What is still missing?