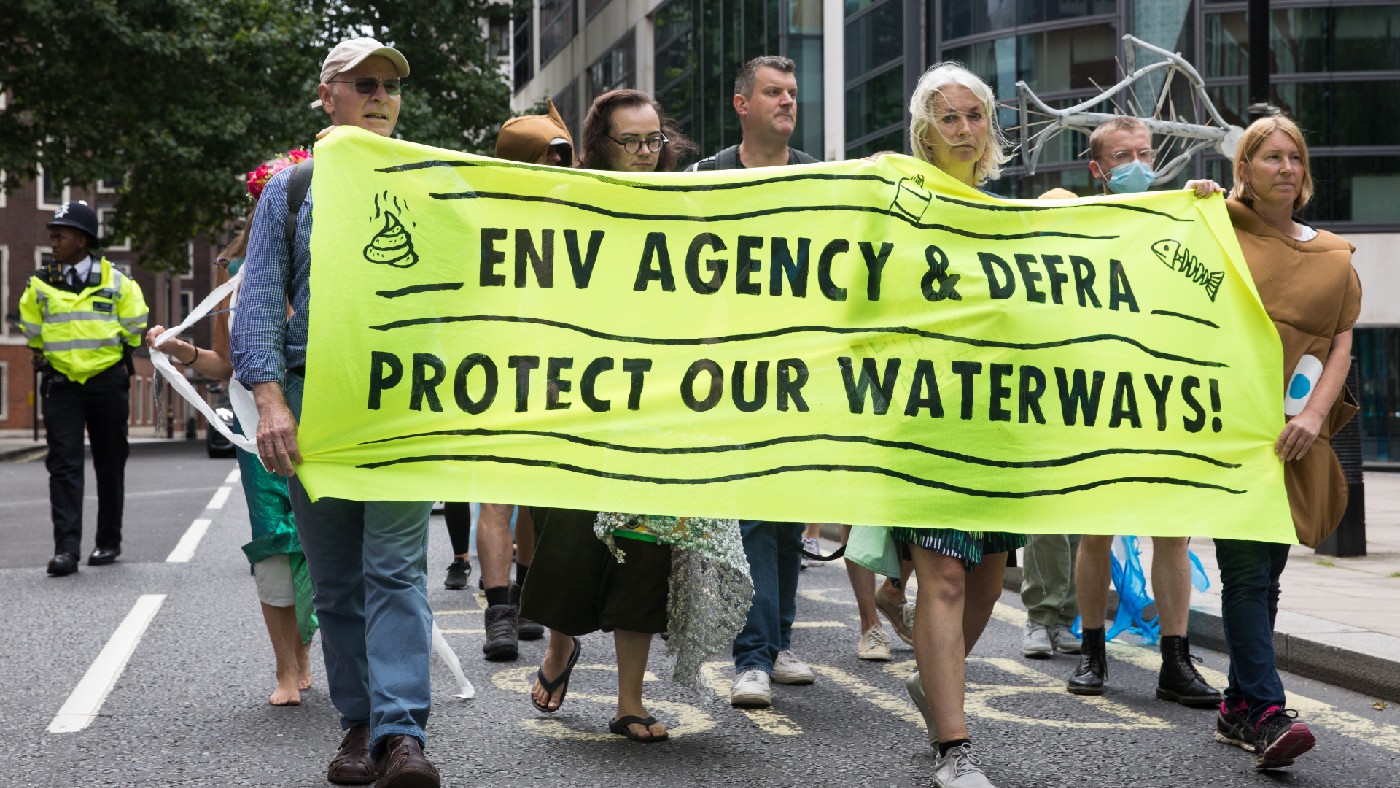

Toxic run-off from cities, oil spills and fly-tipping: the state of England’s rivers

How bad is the problem of pollution in our waterways? And what is being done about it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In July, a record £90m fine was given to Southern Water – following the largest criminal investigation in the Environment Agency’s 25-year history. The water company had pleaded guilty to 51 pollution offences, and to spilling 16-21 billion litres of untreated sewage into the coastal waters and waterways of Kent, Sussex and Hampshire between 2010 and 2015.

But the state of Britain’s rivers, and particularly of England’s rivers, has been a matter of concern for years. The River Wye, on the border of England and Wales, has seen rising levels of algal blooms and declining levels of fish life; its once-clear gravel bottom is now, in many places, coated in green slime.

Campaigners say the River Windrush in Oxfordshire is “literally dying” because of pollution. On the River Wharfe, Yorkshire Water has been routinely discharging human waste upstream of a popular bathing spot. There are also fears that England’s chalk streams, one of the world’s rarest habitats, could be irreparably damaged.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How bad is the problem?

Very. Figures published last year by the Environment Agency (EA) revealed that just 14% of English rivers are classed as being in “good ecological health” under the EU’s Water Framework Directive (which has been retained post-Brexit). These were among the worst figures in Europe.

In Scotland, by contrast, 65.7% of rivers were classed as in good health, and in Wales 64%. For the first time, none of the 4,600 English rivers, lakes and waterways assessed by the EA achieved “good chemical status”.

Why is it happening?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Toxic run-off from cities, oil spills and fly-tipping all contribute to pollution. However, the two main sources are agriculture and water companies. Pesticides, fungicides and fertilisers used in farming, along with animal slurry, all run off the land and into waterways. These have direct toxic effects, as well as creating high levels of phosphates and nitrates in the water, leading to excessive growth of algae – choking river channels and damaging the habitat of other plants, fish and animals.

In the Wye river catchment area, for instance, it is thought that an increase in the number of intensive chicken farms has led to a damaging increase in the amount of phosphates in the river. More shocking, though, and arguably more easily avoidable, is the dumping of sewage directly in rivers by water companies.

How big an issue is sewage?

Water companies discharged raw sewage into rivers and coastal waters in England no fewer than 400,000 times last year, according to the EA. Untreated effluent – including human waste, condoms and wet wipes – poured into rivers and seas for a total of 3.1 million hours via sewage overflow pipes.

In 2019, raw sewage was discharged for 1.5 million hours into rivers alone. The regularity of these discharges means rivers face “death by a thousand cuts”, said Mark Lloyd, chief executive of The Rivers Trust.

On the Windrush, for instance, campaigners say the water upstream of one sewage outlet is mostly clear and healthy; downstream it is cloudy and polluted with human waste, E. coli, domestic cleaning products, hormones and many other contaminants.

Why do these discharges happen?

“Combined sewage overflows” are meant to discharge only during spells of heavy rainfall, to stop sewage backing up into streets and homes. But England’s ageing sewerage network is struggling to cope.

The water companies do face genuine difficulties, because the growing population and the increasing frequency of heavy rainfall are putting more stress on their systems, and the alternatives, such as installing extra storm tank storage or building new sewers, are costly; in London, the Tideway, a vast £4.1bn additional sewer, is being built to capture overflows.

The UK water industry has already invested £30bn in environmental work over 30 years. But environmentalists argue that that isn’t nearly enough; and that the water companies save themselves money by using sewage overflows routinely, not just in emergencies.

Why isn’t the pollution stopped?

Since 2010, the EA’s enforcement funding has been cut by nearly two-thirds, from £120m to just £43m. In a letter obtained under Freedom of Information laws, the EA chair Emma Howard Boyd told George Eustice, the Environment Secretary, that this “has forced us to reduce or stop work it used to fund, with real-world impacts (e.g. on our ability to protect water quality) for which we and the Government are now facing mounting criticism”.

Across England’s 106,000 farms, the EA cut inspections by two-thirds, down from 905 in 2014-15 to 308 in 2019-20. At that rate, the average farm can expect to be inspected once every 344 years.

The rise of the wild swimmer

Swimming outdoors has been a popular British pastime for centuries. Only recently was the term “wild swimming” coined for it – in Roger Deakin’s 1999 book Waterlog, a record of his quixotic quest to swim through the British Isles, via its rivers, lochs, tarns, moats, aqueducts, even the “chocolate water” of its city canals.

Thanks in part to books like Deakin’s, and the closure of public pools during the pandemic, it has become a craze: searches for the term “wild swimming” increased by 94% between 2019 and 2020.

Yet the polluted waterways of the UK can pose serious health risks thanks to harmful bacteria such as E. coli, salmonella and listeria, and – in rare cases – potentially fatal diseases such as leptospirosis and hepatitis A.

The wild swimmers, though, may turn out to be a powerful force for conservation. A stretch of the River Wharfe near Ilkley in Yorkshire last year became the first in the UK to be given “bathing status”, forcing Yorkshire Water and the EA to regularly monitor water quality and publish the results.

From Port Meadow on the Thames in Oxford to the River Almond in Lothian, pushing for bathing water status is being seen as a way of driving clean-up campaigns. The Wharfe was given its first designation in April: “poor quality”.

Will things get better?

The EA insists that, in some respects, they already have: England’s rivers are the cleanest they’ve been since the Industrial Revolution, with pollutants such as ammonia, mercury and cadmium greatly reduced over recent decades. But the EA’s chief executive James Bevan also admits that “not everything is getting better, and some things are getting worse”: notably “water pollution incidents” caused by farms and sewage companies.

In theory, things ought to improve. The Government is bound by the Water Framework Directive to ensure that all waters reach good ecological status by 2027; last month it was announced that the number of EA inspectors targeting farmers who pollute rivers would be trebled.

But campaigners argue that the 2027 target is too far away, and that anyway it will be missed (it was first set for 2015, then 2021). In the meantime, England’s rivers – home to a range of species such as trout, salmon and kingfishers, and beloved of walkers, swimmers and fishermen – continue to suffer grievously.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

How will climate change affect the UK?

How will climate change affect the UK?The Explainer Met Office projections show the UK getting substantially warmer and wetter – with more extreme weather events

-

Are we entering a ‘golden age’ of nuclear power?

Are we entering a ‘golden age’ of nuclear power?The Explainer The government is promising to ‘fire up nuclear power’. Why, and how?

-

Europe's heatwave: the new front line of climate change

Europe's heatwave: the new front line of climate changeIn the Spotlight How will the continent adapt to 'bearing the brunt of climate change'?

-

Storm warning: Will a shrunken FEMA and NOAA be able to respond?

Storm warning: Will a shrunken FEMA and NOAA be able to respond?Feature The U.S. is headed for an intense hurricane season. Will a shrunken FEMA and NOAA be able to respond?

-

Seven wild discoveries about animals in 2025

Seven wild discoveries about animals in 2025In depth Mice have Good Samaritan tendencies and gulls work in gangs

-

Should Los Angeles rebuild its fire-prone neighbourhoods?

Should Los Angeles rebuild its fire-prone neighbourhoods?Talking Point The latest devastating wildfires must be a wake-up call for Los Angels to 'move away from fire-prone suburban sprawl'

-

England's great parakeet invasion

England's great parakeet invasionThe Explainer How did a parrot from the Himalayas become a common sight in southeast England?

-

Decarbonising the national grid

Decarbonising the national gridThe Explainer In theory, Britain's electricity grid will be carbon neutral by 2035. What will that involve? Is it even possible?