Are overpopulation fears unfounded?

Number of people on planet is growing at its slowest rate since 1950, says UN report

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

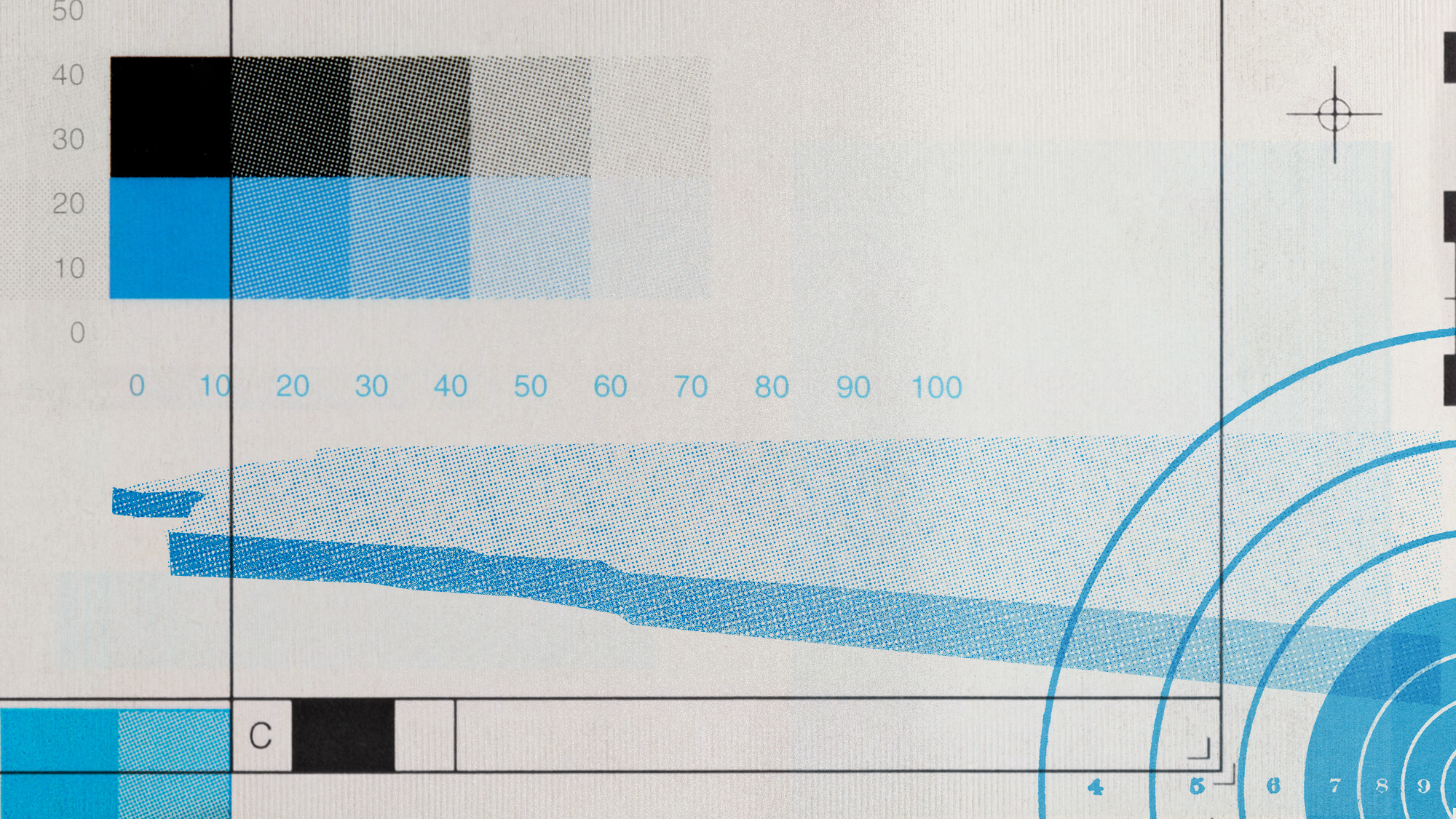

The global population is set to surpass eight billion later this year, according to a United Nations forecast.

But despite the world approaching this mammoth milestone, population growth is actually increasing at its slowest rate since 1950, according to the UN’s World Population Prospects report.

It says that the planet should hit 8.5 billion people in 2030 and 9.7 billion in 2050, peaking at around 10.4 billion in the 2080s before steadying at that level until 2100.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Population growth slowing

The UN’s Secretary-General António Guterres said the milestone was something to welcome, calling it an occasion to “celebrate our diversity, recognise our common humanity, and marvel at advancements in health that have extended lifespans and dramatically reduced maternal and child mortality rates”.

However, he said it was also a reminder of “our shared responsibility to care for our planet”.

Population growth fell to less than 1% in 2020 according to the report, mainly due to a decline in fertility in many countries, which has fallen “markedly” in recent decades.

Today, some two-thirds of the global population live in a country or area where lifetime fertility is below 2.1 births per woman, “roughly the level required for zero growth in the long run, for a population with low mortality”, according to the UN.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 61 countries or areas, the population is expected to decrease by at least 1% over the next three decades, as a result of “sustained low levels of fertility” and in the case of some countries, “elevated rates of emigration”.

More than half of the projected increase in the global population up to 2050 will be concentrated in just eight countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines and the United Republic of Tanzania.

Indeed, India is set to pass China next year to become the world’s most populous nation, while Nigeria is expected to leapfrog the US into third place by 2050.

What are the ramifications?

The English-speaking world is set to be a demographic “winner” in the coming decades, with the US adding to its population right through to the end of the century, reaching 400 million, as will Canada, reaching nearly 54 million, and Australia, with 38 million, said Hamish McRae for the i news site.

China is set to be a demographic “loser” with its population dropping to 770 million by 2100, while the Russian Federation is also in a “precarious position”, with its population of 145 million dropping to just 133 million by 2050 and 112 by the end of the century.

“One [conclusion] is that China will not be the feared dragon in another 50 years it now seems to be,” he wrote. “Another is that the US will continue to be vibrant and important. Still another is that Russia has a demographic challenge of huge proportions.”

“There are also wider issues,” he continued, one of the most pressing questions being: “Can the world feed more than 10 billion people without intolerable strains on the planet’s resources?”

Does overpopulation drive climate change?

The idea that the world’s burgeoning human population could have serious consequences for the planet’s natural resources has been around since the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the publication of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and Donella Meadows’ The Limits to Growth.

And it is an idea that persists today. In 2020, at the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, “famed primatologist Dr Jane Goodall remarked at the event that human population growth is responsible for the climate crisis, and that most environmental problems wouldn’t exist if our numbers were at the levels they were 500 years ago,” noted Heather Alberro, associate lecturer in political ecology at Nottingham Trent University, in The Conversation.

But although a seemingly “innocuous” comment, it is an argument that has “grim implications”. Most importantly, “focusing on human numbers obscures the true driver of many of our ecological woes”, especially as the rate at which the global population grows is slowing, she argues.

In 2018 the planet’s top emitters, North America and China, accounted for nearly half of global CO2 emissions. The comparatively high rates of consumption in these regions generate so much more CO2 than their counterparts in low-income countries that “an additional three to four billion people in the latter would hardly make a dent on global emissions”, she writes.

Indeed, since the start of the millennium, “UN reports show that global resource use has been primarily driven by increases in affluence, not the population”, said The Washington Post.

This is “especially true in high- to upper-middle-income nations, which account for 78% of material consumption, despite having slower population growth rates than the rest of the world”, said the paper.

Meanwhile, in low-income countries, whose share of the global population has “almost doubled”, the demand for resources has “stayed constant at just about 3% of the global total”.

And concentrating on global population numbers isn’t just “misguided”, it can be “dangerous”, added the paper. When concern about population becomes central to environmental policy, said researcher Betsy Hartman, “racism and xenophobia are always waiting in the wings”.

“It just shifts the discourse away from the real problem of who has power and how the economy is organized.”

Challenges await

Nevertheless, “the challenges the pessimists anticipate aren’t imaginary”, said Vox. We have yet to figure out how to provide almost 11 billion people with a good standard of sustainable living in the year 2100.

But green and sustainable technology has been “rapidly improving” for some time, and with the population peak set to hit in almost 100 years it is helpful to remember that “almost all the technology that we have today to make civilization sustainable sounded like wild science fiction 80 years ago”.

Another reason for hope is that almost all analysts and population models agree that “without any totalitarian or coercive measures, populations will start declining”. The main point of disagreement “is simply when”.

While the slow down of population growth comes with some concerns, such as ageing and shrinking workforce, “on the whole, we are much better positioned for sustainable growth than it looked in 1950”, said Vox.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

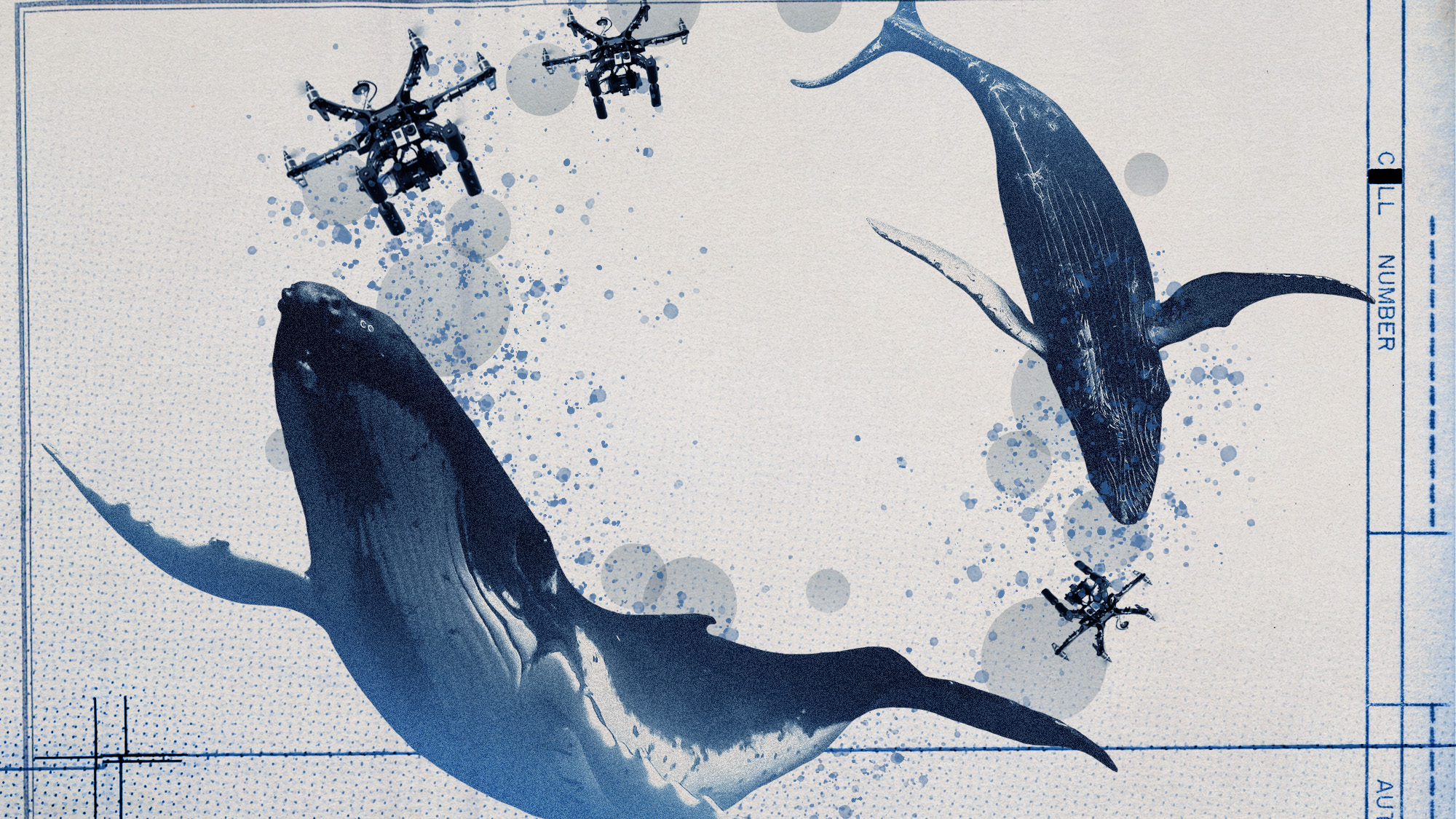

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures