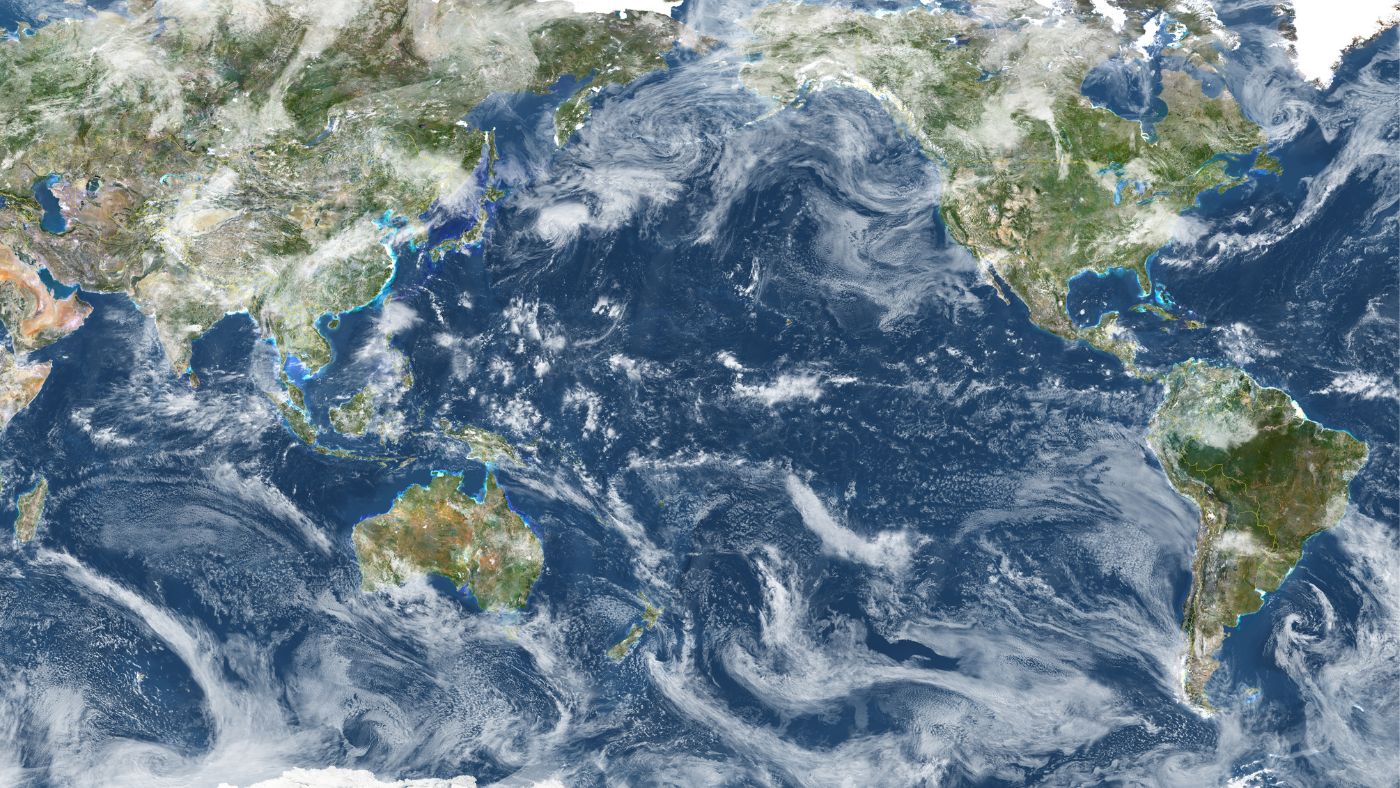

‘Cold tongue’: what the Pacific Ocean cool patch mystery says about climate change

One part of the Pacific Ocean is baffling scientists, but the broad trajectory of oceanic temperatures remains clear

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A thin stretch of the eastern Pacific Ocean has been getting colder for the past 30 years, defying the broad global trend and baffling scientists.

The anomaly, known as the “equatorial cold tongue”, is affecting an area that extends west from the coast of Ecuador for thousands of miles.

Over at least three decades the region has cooled by roughly half a degree and it “has scientists wondering how long that will hold”, said The Atlantic.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is causing the ‘cold tongue’?

Scientists are not entirely certain what is keeping the “cold tongue” cool. But Richard Seager, from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, said one factor appears to be trade winds in the region, which carry warm water away from the surface stimulating cooler water to rise.

“The trade winds blow from east to west across the tropical Pacific Ocean,” Seager told Newsweek. “Because of the rotation of the Earth, the winds drive waters northward to the north of the Equator and southward to the south of the Equator. As the waters are driven away from the Equator, water is pumped up from below and since the waters below the surface are cold this creates the equatorial Pacific cold tongue.”

Yet despite the effect of these winds, the cold tongue has “puzzled scientists”, Newsweek said, “because advanced climate computer models suggest that the waters should have been warming for decades at a faster rate than the rest of the Pacific due to rising greenhouse gas emissions”.

Other hypotheses suggest that the answer may be found in the cold seas of the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, which have also seen sea surface temperatures decline in recent decades.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Suspected drivers include the melting of Antarctic glaciers as global temperatures rise, and ozone depletion in conjunction with rising greenhouse gas emissions, which are intensifying the movement of cold air from Antarctica.

Why does it matter?

This isn’t just an “academic puzzle”, New Scientist said. In fact, according to Pedro DiNezio, at the University of Colorado Boulder, it is “the most important unanswered question in climate science”.

Not knowing what is causing it “means we also don’t know when it will stop, or whether it will suddenly flip over into warming”, New Scientist added. This has huge worldwide implications and “could determine whether California is gripped by permanent drought or Australia by ever-deadlier wildfires” as well as “the intensity of monsoon season in India and the chances of famine in the Horn of Africa”.

More profoundly still, “it could even alter the extent of climate change globally”, the site said, “by tweaking how sensitive Earth’s atmosphere is to rising greenhouse gas emissions”.

What are its effects on wildlife?

As well as the climate-related questions it presents, the cold tongue is also of interest to biologists, particularly in relation to the Galápagos Islands, which lie about 600 miles off Ecuador.

This is because the “cold, nutrient-rich water” of the cold tongue has become a “prosperous patch [that] feeds phytoplankton and breathes life into the archipelago”, said The Atlantic.

According to Judith Denkinger, a marine ecologist at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador, the ecological impacts of the cold tongue are profound.

“The cool water sustains populations of penguins, marine iguanas, sea lions, fur seals, and cetaceans that would not be able to stay on the equator year-round,” Denkinger told The Atlantic.

Colder temperatures can also “inhibit coral growth rates” and “fish may experience shifts in their distribution due to changes in water temperature, which can also affect their metabolism and reproduction”, said Brilliantio in its explainer on temperature in the Pacific Ocean.

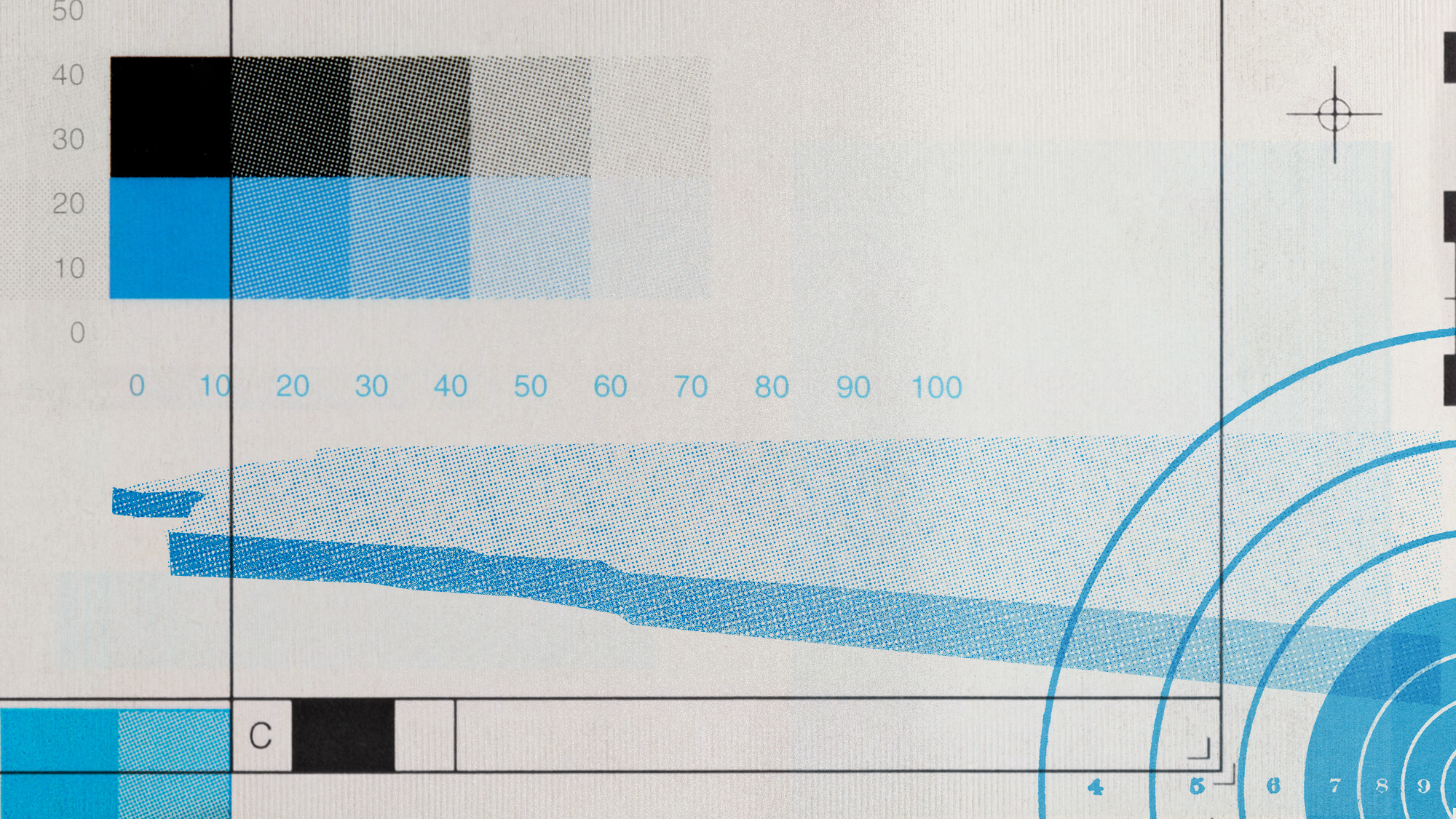

Do cooler waters challenge existing climate models?

As well as the cold tongue, other pockets of cool oceanic water sporadically present themselves, such as an area of the Pacific Ocean near San Francisco that has recently been the coldest it’s been in more than a decade.

Despite this, the overall direction of ocean temperatures is going up, said Ryan Walter, associate professor at California Polytechnic State University. “We know that long term there’s climate change and warming,” Walter told the San Francisco Chronicle. “In the meantime, you have all these ups and downs.”

Solving the puzzle of the cold tongue “isn’t about proving climate models wrong”, said New Scientist. “On the big issues… they have been remarkably accurate.

“Rather, the cold tongue is the last big piece of the puzzle. Fit that in and we can build a more accurate picture of how life will change in a warming world – and how best to prepare for that future.”

Arion McNicoll is a freelance writer at The Week Digital and was previously the UK website’s editor. He has also held senior editorial roles at CNN, The Times and The Sunday Times. Along with his writing work, he co-hosts “Today in History with The Retrospectors”, Rethink Audio’s flagship daily podcast, and is a regular panellist (and occasional stand-in host) on “The Week Unwrapped”. He is also a judge for The Publisher Podcast Awards.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

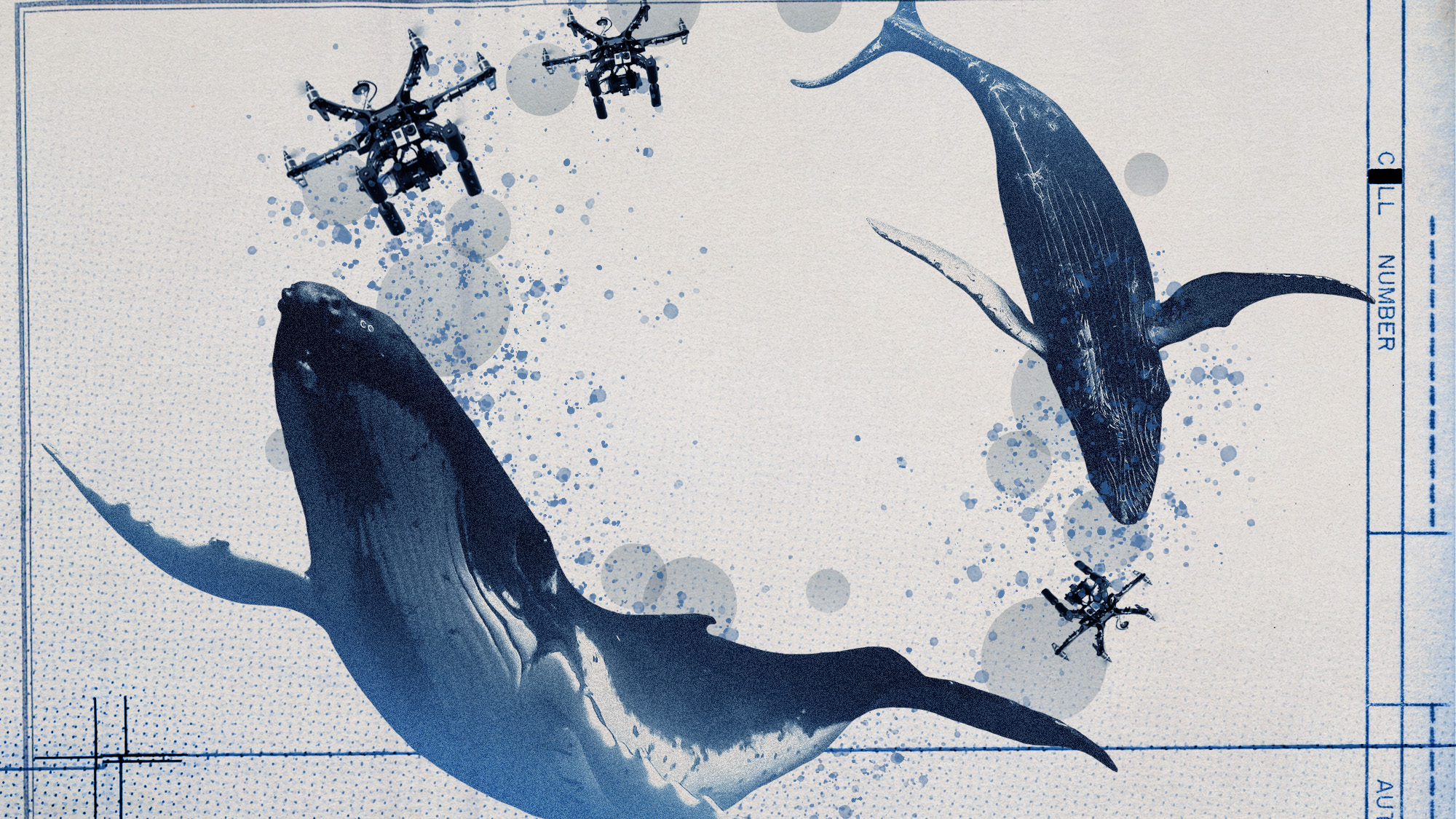

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures