The opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb 100 years on

This month marks a century since Tutankhamun’s tomb was opened for the first time in three millennia

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tutankhamun is sometimes described as the “most famous and least important of the pharaohs”. But unlike Ramesses II (aka Ozymandias), Cleopatra, or Khufu (aka Cheops), who built the Great Pyramid, he was almost completely forgotten after his death.

He was a minor child king, of the 18th dynasty of pharaohs, who ruled Egypt for around nine years from about 1332BC until his death, aged 18 or 19, in about 1323BC. His direct family line died with him and, under his successors, he and his relatives were removed from the official king lists, and many of their monuments were defaced.

He was buried in an unusually small tomb in the Valley of the Kings on the Nile’s west bank, opposite his capital, Thebes (modern Luxor). Its entrance was hidden by rubble from the later digging of Ramesses VI’s tomb and remained near-perfectly preserved for more than 3,000 years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How was the tomb found?

By a team led by Howard Carter, an English artist turned Egyptologist. Most tombs in the Valley of the Kings had been systematically looted, starting in the 12th and 11th centuries BC. They had been tourist attractions since Roman times, and had been dug up and plundered anew since the early 19th century. In 1912, an American-led team gave up the right to dig there, convinced there were no more tombs to be found.

Carter took over in 1915, under the sponsorship of the Earl of Carnarvon, an English aristocrat and collector of antiquities who had been made very rich by his marriage to Alfred de Rothschild’s illegitimate daughter. Carter’s team searched fruitlessly for years. Carnarvon was about to pull the funding when, on 4 November 1922, the first step of the tomb’s entrance staircase was found. Carter sent a telegram to his patron: “At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact.”

What did they find?

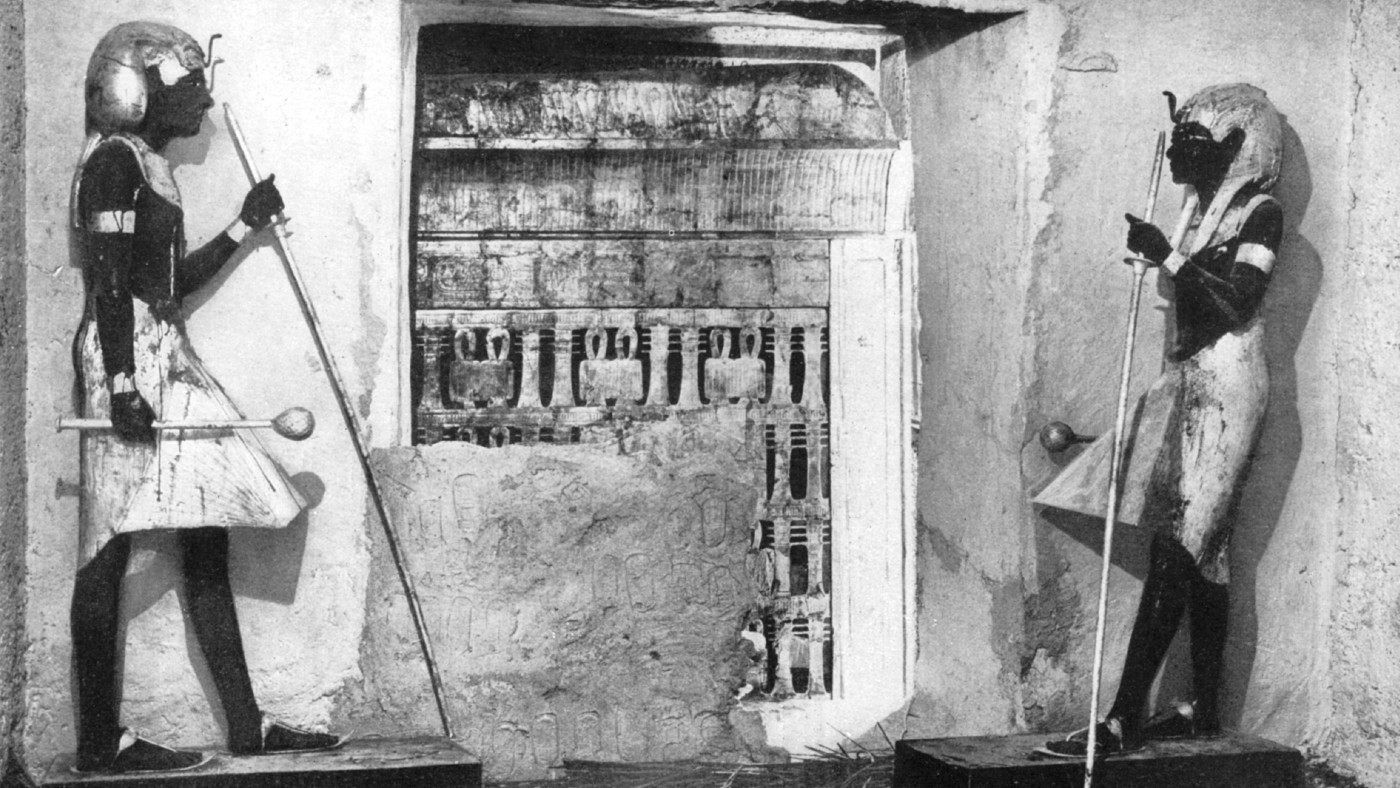

Carnarvon returned to Egypt to witness Carter opening the tomb. “Can you see anything?” he asked, as Carter held up a candle inside the tomb’s doorway. “Yes, wonderful things!” Carter replied. It seems that grave robbers had taken oils and perfumes from Tutankhamun’s tomb soon after his burial, but that ancient officials had repaired the damage and resealed it.

Otherwise, forgotten and buried underneath rubble and workmen’s huts, its contents were largely intact. They included Tutankhamun’s death mask, now probably the most famous artwork from ancient Egypt, and his sarcophagus, with an innermost coffin made of 110.4kg of gold. There were more than 5,000 objects in all, including six chariots, statues of deities, and many walking sticks – as the pharaoh had a deformed left foot.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What was the reaction?

Carter’s find, publicised with dramatic photographs in The Times, caused a media frenzy, and unleashed the biggest wave of “Egyptomania” since the early 1800s, when discoveries made during Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign had a similar effect. The pharaoh was given a tabloid nickname, “King Tut”.

US president Herbert Hoover gave his dog the same name, which also featured in Jazz Age novelty songs such as Old King Tut. Flappers wore pharaonic cobra headbands, and art deco designers put Egyptian motifs on everything from fridges to the Chrysler Building in New York.

In Britain, Carter and Carnarvon were hailed as heroes. Carnarvon’s sudden death in 1923 only added to the excitement, with newspaper speculation about a “curse of the pharaohs”, which inspired Boris Karloff’s The Mummy, Tintin’s adventure Cigars of the Pharaoh and the like.

What did the Egyptians think?

The excavations became a charged political issue; Egypt had won limited independence from Britain in February 1922. For Egyptian nationalists, Tutankhamun’s treasure was proof of the country’s ancient greatness and needed to stay in Egypt; British control of the dig was widely resented.

Carter and Carnarvon, however, had started work under the colonial “partage” system, which would have let them keep half their finds, and they’d promised some of it to foreign museums. Carter squabbled bitterly with the Egyptian government during the ten years it took him to clear the tomb, at one point going on strike. The government eventually won, and the treasures mostly stayed in Egypt, though Carter and his team smuggled out some pieces.

What have we learnt since?

A DNA study in 2010 revealed that Tutankhamun’s parents were brother and sister (although other studies have suggested that he could also have been the product of a long chain of first-cousin marriages). The evidence seems to confirm that he was the son of the pharaoh Akhenaten, a religious revolutionary who turned his back on the old Egyptian gods in favour of worship of Aten, the sun disk; Tutankhamun restored the old religion during his reign (his royal name honours the old patron deity, Amun).

It appears that he married his own half-sister, Ankhesenamun; two babies were buried with him, thought to be the couple’s daughters. The cause of his own death remains much debated; an X-ray study from 1968 purporting to show that he was murdered by a blow to the head has been debunked by CT scans.

What became of Tutankhamun?

He lives on as a prominent symbol of Egypt. Post-Suez, travelling exhibitions of his grave goods played an important role in Egyptian cultural diplomacy. A rapprochement between Richard Nixon and Anwar Sadat led to a blockbusting tour of the US in 1976-79, attracting eight million visitors.

Nearly the complete contents of his tomb will be on display at the $1bn Grand Egyptian Museum when it finally opens next year. Tutankhamun himself still lies in his tomb outside Luxor. Visitors can stare at his mummified and much-autopsied remains, displayed in a climate-controlled glass box.