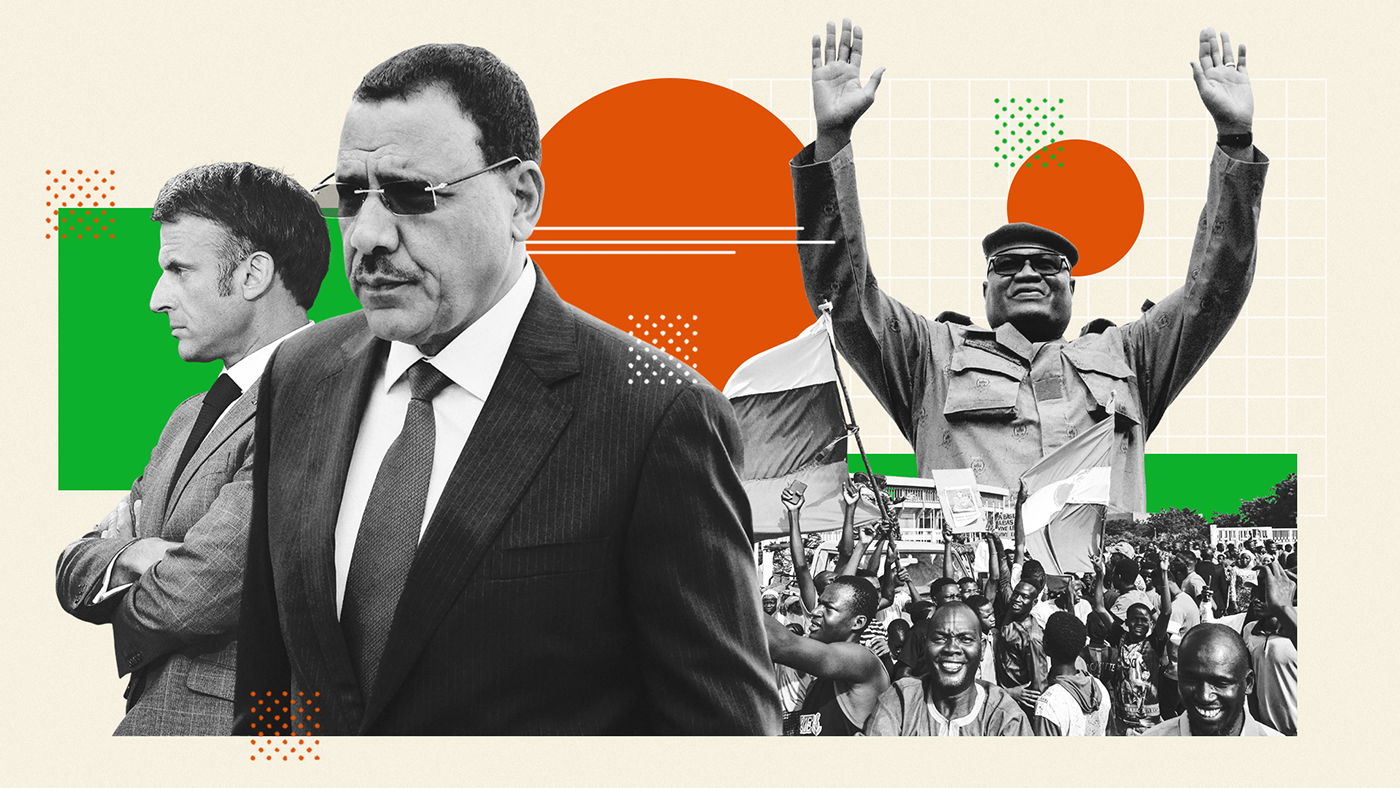

Niger coup: is this the end of French influence in Africa?

Emmanuel Macron’s wish to reset ties between Paris and West Africa may be ‘too little, too late’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

France’s historic influence in West Africa could finally be coming to an end after a succession of coups culminating in last week’s military takeover in Niger.

In the past three decades more than three-quarters of the 27 coups in sub-Saharan Africa have occurred in Francophone states, noted the BBC, “leading some commentators to ask whether France – or the legacy of French colonialism – is to blame?”

What did the papers say?

“First, there was Mali; then came Burkina Faso,” said UnHerd columnist Thomas Fazi. And now “it is the turn of Niger to play the protagonist… in the epic saga that is the anti-Western revolt sweeping across the Sahel”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Much of the anger driving the succession of recent coups has been directed towards the countries’ former colonial master: France. More than any other imperial power, it has “continued to exercise a huge influence over its former outposts, replacing outright colonial rule with more subtle forms of neocolonial control”, said Fazi.

So the current crisis in Niger can “be linked to former colonial relationships being restructured as Françafrique – a formidable neocolonial nexus across sub-Saharan Africa encompassing economic, political, security and cultural ties and alliances centred on the French language and values”, said The Guardian.

A colonial form of governance designed to extract valuable resources through the use of repression is not unique to the French. But what is “distinctive” about its role in Africa, said the BBC, is “the extent to which it continued to engage – its critics would say meddle – in the politics and economics of its former territories after independence”.

Successive French leaders dating back to Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s have viewed western Africa as very much within their rightful sphere of influence. They have used the French language, aid, security assistance and most effectively currency – through the African Financial Community (CFA) franc which is pegged to the euro – to maintain influence in the region.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

France’s big problem now, said The Guardian, is that “Nigeriens – like so many Africans – are rejecting Françafrique with as much fervour as their forebears came to reject the official French Empire”. In this sense, “France’s traditional dominance is disintegrating”, added the paper.

What next?

Aware of the growing opposition to French influence, President Emmanuel Macron has promised to “reset” ties between Paris and Africa, going so far as to declare earlier this year that the era of Françafrique “is over”.

“The trouble is that this rethink may, in essence, be too little too late,” said The Economist.

According to The New York Times, “France has become a scapegoat of sorts in a region buckling under the forces of poverty, climate change and surging Islamist militancy”.

At the same time the French have been unable to find a “credible way to counter the post-colonial narrative of occupation and exploitation that is efficiently used against it”, said The Economist. It is, for example, the only former colonial power to maintain major permanent military bases on the continent, unlike Belgium, Britain and Portugal.

In Niger, despite the illusion of complete withdrawal, France still maintains a garrison of 1,500 troops, together with an air force base servicing fighter jets and attack drones.

“All of this is a forceful reminder,” said The Guardian, “that in spite of a long and bloody period of decolonisation, France has retained a quasi-empire in Africa by stealth, and it is under threat like never before.”

By contrast, China, Russia and Turkey have been quietly building economic influence in the region by lending, investing or securing contracts in West Africa. While France accounts for less than 5% of Africa’s international trade – down from 10% in 2000 – China is now the chief source of imports to the region. Other European countries and the US have increasingly taken up the French mantle as the “Gendarme of Africa”, training counter-terrorism forces in the Sahel.

All this “feeds into fears that we are on the verge of a new scramble for Africa”, said Fazi, “with Russia, China and the West vying for influence over this immensely resource-rich, young continent predicted to be the next frontier of growth”.

The reset in relations may have been a “crucial part of Macron’s foreign policy”, reported Al Jazeera, but it is the former colonies that are now “the ones deciding what ties they want with Paris”.

Elliott Goat is a freelance writer at The Week Digital. A winner of The Independent's Wyn Harness Award, he has been a journalist for over a decade with a focus on human rights, disinformation and elections. He is co-founder and director of Brussels-based investigative NGO Unhack Democracy, which works to support electoral integrity across Europe. A Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellow focusing on unions and the Future of Work, Elliott is a founding member of the RSA's Good Work Guild and a contributor to the International State Crime Initiative, an interdisciplinary forum for research, reportage and training on state violence and corruption.