Why some PCR results were negative after a positive lateral flow test

Investigation leads back to ‘isolated incident’ at private lab in Wolverhampton

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The government has halted Covid-19 testing at a private lab in Wolverhampton after at least 43,000 people were incorrectly given a negative PCR test result.

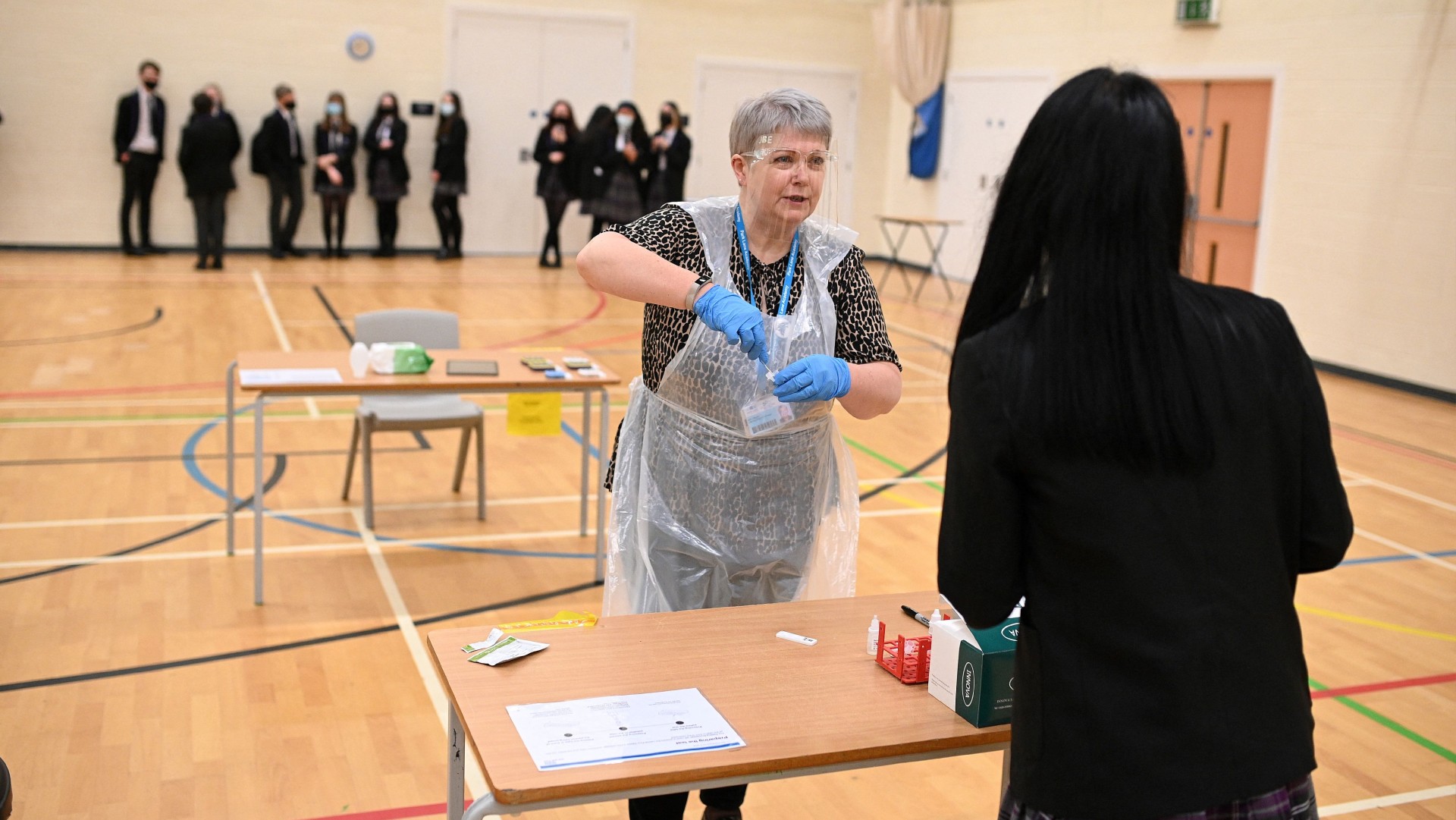

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), formerly Public Health England, began an investigation after seeing a rapid rise in negative Covid-19 results from PCR tests following positive lateral flow tests among schoolchildren.

The proportion of pupils testing positive on a home Covid-19 kit and then getting “the apparent all-clear” by the “gold-standard” PCR almost doubled within a week, reported Tom Whipple, science editor at The Times.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Out of 14,000 secondary school children in England whose lateral flow tests (LFTs) were positive in the third week of September, 7% (957) turned out to be negative in a laboratory PCR. This proportion rose to 12.5% (2,000 out of 16,000) the following week.

The rise in people testing positive on multiple lateral flows before testing negative on multiple PCRs sparked a number of theories, from a faulty batch of LFTs or a new variant of Covid undetectable by PCRs to different swabbing techniques and children faking positive lateral flow results.

The UKHSA ruled out the possibility of a new variant as the cause and initially said that there was no evidence of “technical issues” with PCR testing kits. However, the agency’s chief medical adviser Susan Hopkins did urge the public to “carefully read and follow the instructions for use on the test kit so as to avoid any incorrect readings”, GP Online reported.

Catherine Moore, consultant clinical scientist in virology for Public Health Wales, had a different theory. She suggested that the false positive results could have been associated with higher mucus levels due to it being the cold and season.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the end, the phenomenon was traced back to the Immensa Health Clinic in Wolverhampton, which the UKHSA described as an “isolated incident attributed to one laboratory”.

NHS Test and Trace estimated that of the 400,000 coronavirus test samples processed through the lab between 8 September and 12 October, around 43,000 people may have been given incorrect results, mostly in the south west of England.

“The number of tests carried out at the Immensa laboratory are small in the context of the wider network and testing availability is unaffected around the country,” said the UKHSA statement.

All samples are now being redirected to other labs and NHS Test and Trace is contacting the people that could still be infectious to advise them to take another test.

It is still unclear exactly how the problem was discovered and what was going on inside the lab to cause the mistakes to happen. Speaking on The Guardian’s Science Weekly podcast, mathematical biologist Kit Yates said there had been suggestions that the quality assurance process had been “bypassed” to deal with the surge in PCR testing required when children went back to school at the start of September.

Yates said that someone should have spotted sooner that the lab’s positivity rate was about 1-1.25%, compared to the national average of 12%. “It shouldn’t have taken amateur data scientists and scientific sleuths to point out this problem,” he added.

The biologist was keen to uphold listeners’ faith in PCR testing. “One thing we need to be careful about is the fact that this is one – or seemingly one – rogue lab and shouldn’t damage people’s confidence in PCR testing,” he said.

“The PCR tests are still very accurate and reliable, but it seems like this one lab has not been doing a proper job with their PCR tests.”

Andrea Riposati, CEO of the Immensa Health Clinic, said that the lab was “fully collaborating” with the UKHSA. “We have proudly analysed more than 2.5 million samples,” he said, adding: “We do not wish this matter or anything else to tarnish the amazing work done by the UK in this pandemic.”

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

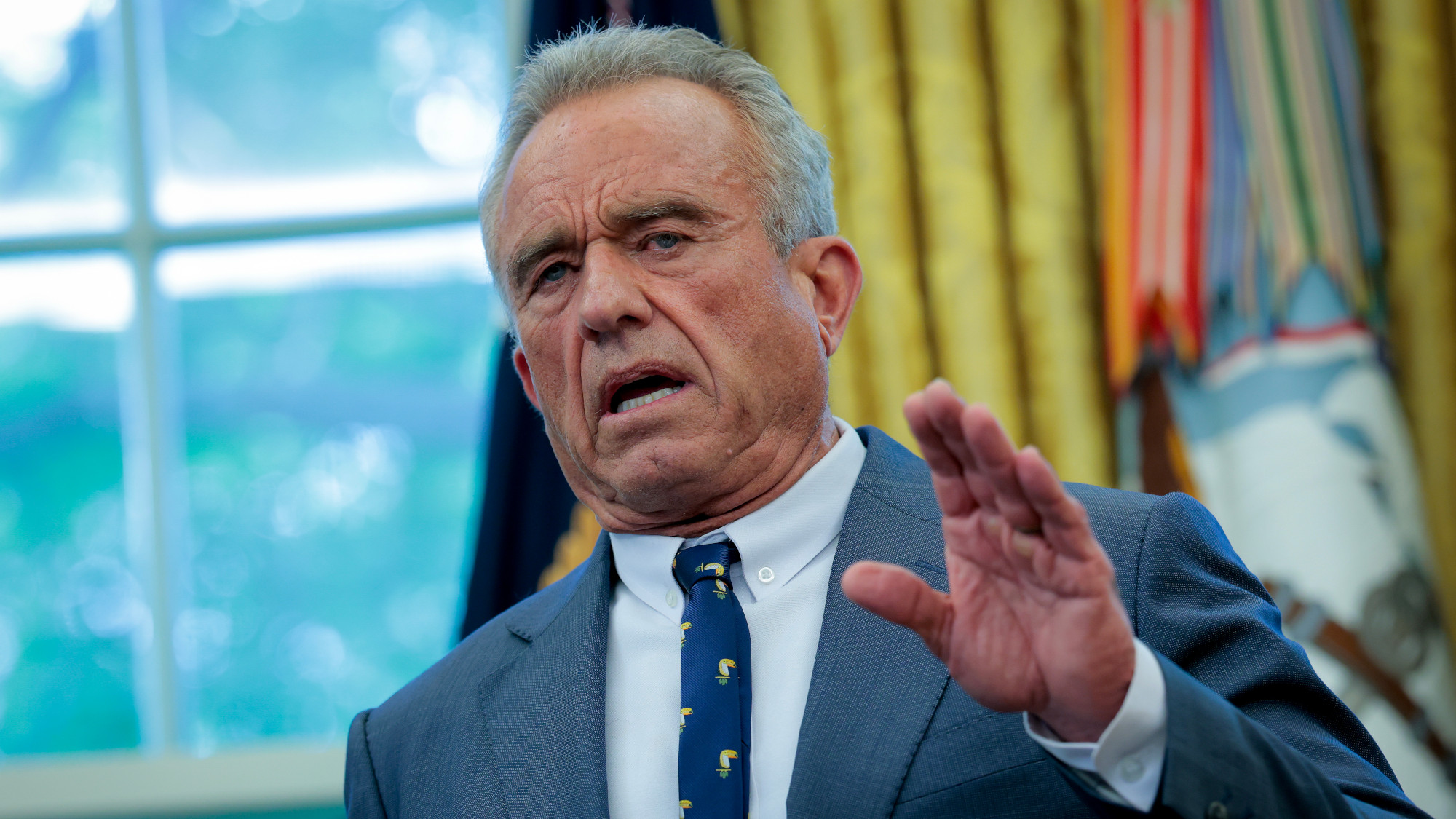

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics