Legalising assisted dying: a complex, fraught and ‘necessary’ debate

The Assisted Dying Bill – which would allow doctors to assist in the deaths of terminally ill patients – has relevance for ‘millions’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The UK’s largest doctors’ union has dropped its long-standing opposition to assisted dying following a landmark vote at their annual meeting.

Last week, British Medical Association (BMA) members voted to adopt a neutral stance on assisted dying, with 49% in favour, 48% opposed and 3% abstaining, reported Sky News. All forms of assisted dying are currently illegal under English law.

In a statement, the BMA added that although the neutral stance means the union “will neither support nor oppose attempts to change the law”, it will “not be silent on the issue” of assisted dying.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“We have a responsibility to represent our members’ interests and concerns in any future legislative proposals and will continue to engage with our members to determine their views,” the statement continued.

The BMA’s vote was made with the assumption that any legalised dying is only accessible for adults, those with the mental capacity to make the decision, those with either a terminal illness or serious physical illness causing intolerable suffering that cannot be relieved, and is a voluntary request by the adult in question.

Before September’s vote, the BMA had opposed assisting dying in all forms since 2006, reaffirming their position in 2016. Since 2009, the Royal College of Nursing has adopted a neutral stance in relation to assisted dying for people with a terminal illness.

Campaigners for assisted dying welcomed the result of the vote, describing it as a “historic milestone”. Many feel that the BMA’s neutral stance could help pave the way towards a future change in the law, said The Guardian.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The ethical arguments and definitions

Those in favour of euthanasia or assisted dying say that in a civilised society, people should be able to choose when they are ready to die and should be helped if they are unable to end their lives on their own.

But some critics take a moral stance against euthanasia and assisted suicide, saying life is given by God and only God can take it, says the BBC. Others think that laws allowing euthanasia could be abused and people who didn’t want to die could be killed.

The terminology around euthanasia is sometimes inconsistently applied, but there is a difference between euthanasia, assisted suicide and assisted dying, says The Guardian.

Euthanasia refers to an instance where active steps are taken to end someone’s life, but the fatal act is carried out by someone else, such as a doctor. Assisted suicide is when someone takes their own life but is assisted by somebody else. Rather than a doctor carrying out the fatal act, they themselves do so.

Assisted dying can refer to either euthanasia or assisted suicide.

Under the Suicide Act 1961, both euthanasia and assisted suicide are criminal offences in the UK. Euthanasia can result in a murder charge, and assisted suicide by aiding or even counselling somebody in relation to taking their own life is punishable by 14 years’ imprisonment.

Which countries have legalised euthanasia?

The number of countries which have legalised euthanasia or assisted dying - usually under strict conditions - is growing.

Switzerland

Probably the first country that comes to mind in relation to assisted dying, Switzerland allows physician-assisted suicide without a minimum age requirement, diagnosis or symptom state.

However, assisted suicide is deemed illegal if the motivations are “selfish” - for example, if someone assisting the death stands to inherit earlier, or if they don’t want the burden of caring for a sick person.

Euthanasia is not legal in the country.

In 2018, 221 people travelled to the Swiss clinic Dignitas for assisted suicide. Of these, 87 were from Germany, 31 from France and 24 from the UK. According to the Campaign for Dignity in Dying, a British person travels to Dignitas for help to die every eight days.

About 1.5% of Swiss deaths are the result of assisted suicide.

Netherlands

Euthanasia and assisted suicide are legal in the Netherlands in cases where someone is experiencing unbearable suffering and there is no chance of it improving. There is no requirement to be terminally ill, and no mandatory waiting period.

In October 2020, the Dutch government approved plans to allow euthanasia for terminally ill children aged between one and 12. The health ministry said the rule change would prevent some children from “suffering hopelessly and unbearably”, the BBC reported.

Parental consent is needed for those under 16.

There are various checks that have to be undertaken before assisted dying can be approved. Doctors who are considering allowing assisted dying must consult with at least one other, independent doctor to confirm that the patient meets the necessary criteria.

Spain

In March 2021, Spain made it legal for people to end their own life in some circumstances.

The law allows adults with “serious and incurable” diseases that cause “unbearable suffering” to choose to end their lives, reported the BBC. The adult must be a Spanish national or legal resident and be “fully aware and conscious” when they make the request, which has to be submitted twice in writing.

Before the law was passed, assisting someone to die in Spain was punishable with up to ten years in jail.

Belgium

Belgium allows euthanasia and assisted suicide for those with unbearable suffering and no prospect of improvement. If a patient is not terminally ill, there is a one-month waiting period before euthanasia can be performed.

Belgium has no age restriction for children, but they must have a terminal illness to meet the criteria for approval.

Luxembourg

Assisted suicide and euthanasia are both legal in Luxembourg for adults. Patients must have an incurable condition with constant, intolerable mental or physical suffering and no prospect of improvement.

Canada

In March 2021, Canada expanded its law on assisted dying. Now adults with a serious and incurable “disease, illness or disability”, who are in an advanced state of decline and are suffering, are able to seek a medically assisted death - even if they are not dying, said The Times.

Previously, the country had only permitted euthanasia and assisted suicide for adults suffering from “grievous and irremediable conditions” whose death is “reasonably foreseeable”.

Medically assisted deaths counted for 1.89% of all deaths in Canada in 2019, reported the BBC.

In Quebec, only euthanasia is allowed.

Colombia

Colombia was the first Latin American country to decriminalise euthanasia, in 1997, and the first such death happened in 2015.

In July 2021, the Constitutional Court of Colombia extended the law on euthanasia or assisted death to include cases of non-terminal illnesses “provided that the patient is in intense physical or psychological suffering, resulting from bodily injury or serious and incurable illness”, reported The Rio Times.

Australia

The Australian state of Victoria was the country’s first to pass voluntary euthanasia laws, which happened in November 2017 after 20 years and 50 failed attempts. The Australian Senate had previously repealed the law in 1997 owing to a public backlash against the 1995 law that allowed it.

To qualify for legal approval, you have to be an adult with decision-making capacity, you must be a resident of Victoria, and have intolerable suffering due to an illness that gives you a life expectancy of less than six months, or 12 months if suffering from a neurodegenerative illness.

A doctor cannot bring up the idea of assisted dying; the patient must raise it first. You have to make three requests to the scheme, including one in writing. You must then be assessed by two experienced doctors, one of whom is a specialist, to determine your eligibility, said The Guardian.

If eligible, you will be prescribed drugs which you must keep in a “locked box” until a time of your choosing. If you can’t administer the fatal drugs yourself, a doctor can administer a lethal injection.

Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania have since joined Victoria in legalising voluntary assisted dying. And, in September 2021, Queensland became the fifth Australian jurisdiction to allow voluntary euthanasia, with an overwhelming majority of MPs voting in favour despite the state being one of the most conservative.

Voluntary assisted dying will be restricted to people with an advanced and progressive condition that causes intolerable suffering and which is expected to cause death within a year, reported The Guardian.

USA

Several states now offer legal assisted dying. Oregon, Washington, Vermont, California, Colorado, Washington DC, Hawaii, New Jersey, Maine, Montana and New Mexico all have laws or court rulings allowing doctor-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients.

Doctors can write patients a prescription for the fatal drugs, but a healthcare professional must be present when they are administered.

All of the states require a 15-day waiting period between two oral requests and a two-day waiting period between a final written request and the fulfilling of the prescription.

France

Palliative sedation, in which someone can ask to be deeply sedated until they die, is permitted in France, but assisted dying is not.

In April 2021, a proposal to legalise assisted dying for people with incurable diseases was blocked in the French parliament.

Neither President Emmanuel Macron nor his government weighed in on the debate, although in 2017 Macron was quoted as saying “I myself wish to choose the end of my life”, reported France 24.

New Zealand

In October 2020, New Zealand voted to legalise euthanasia in what campaigners have called “a victory for compassion and kindness”, the BBC reported.

The law will allow terminally ill people with less than six months to live the opportunity to choose assisted dying if approved by two doctors. It is expected to come into effect in November 2021.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Growing a brain in the lab

Growing a brain in the labFeature It's a tiny version of a developing human cerebral cortex

-

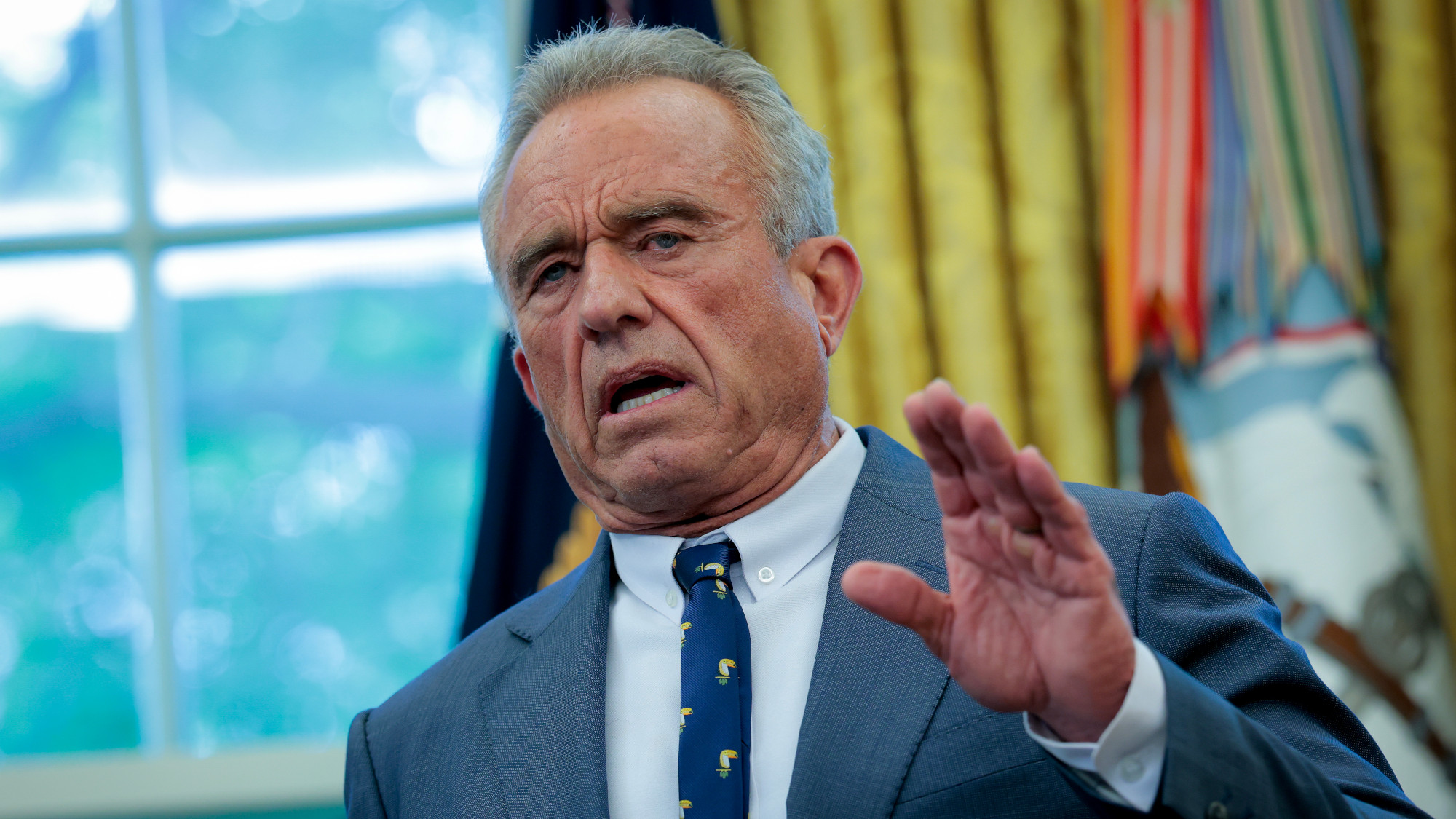

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

Obesity drugs: Will Trump’s plan lower costs?

Obesity drugs: Will Trump’s plan lower costs?Feature Even $149 a month, the advertised price for a starting dose of a still-in-development GLP-1 pill on TrumpRx, will be too big a burden for the many Americans ‘struggling to afford groceries’

-

Ultra-processed America

Ultra-processed AmericaFeature Highly processed foods make up most of our diet. Is that so bad?

-

The quest to defy ageing

The quest to defy ageingThe Explainer Humanity has fantasised about finding the fountain of youth for millennia. How close are we now?

-

The battle of the weight-loss drugs

The battle of the weight-loss drugsTalking Point Can Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly regain their former stock market glory? A lot is riding on next year's pills

-

An insatiable hunger for protein

An insatiable hunger for proteinFeature Americans can't get enough of the macronutrient. But how much do we really need?

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'