Fighting against fluoride

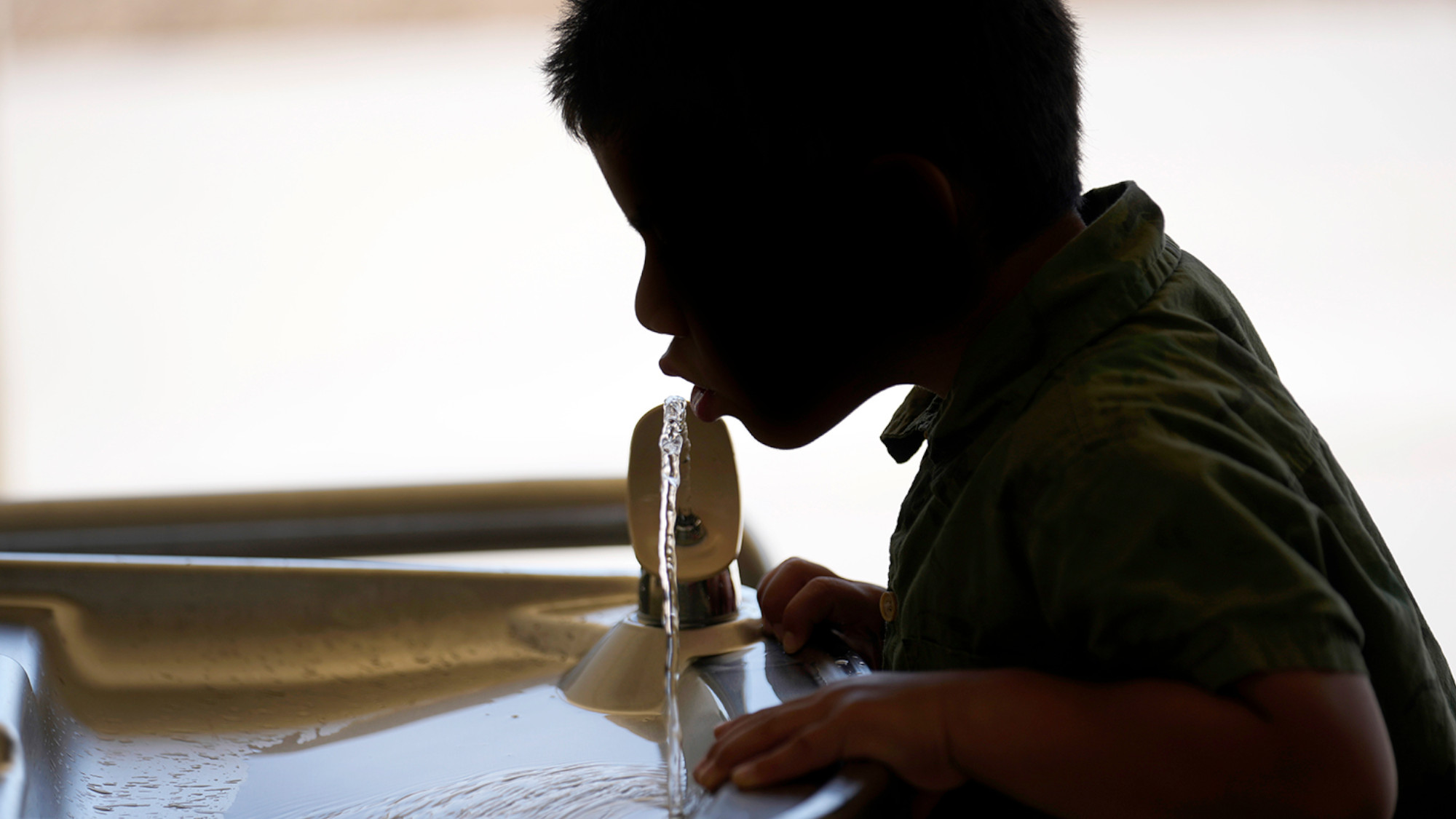

A growing number of communities are ending water fluoridation. Will public health suffer?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why do we add fluoride to water?

Because it helps keep teeth strong, replacing minerals that are lost during regular wear and tear. Grand Rapids, Mich., became the first city in the world to add fluoride to its public water in 1945; within 11 years, the amount of tooth damage from decay among the city's children had dropped by 60 percent. About 72 percent of Americans served by public water systems now drink fluoridated water, and the process is estimated to save about $6.5 billion in dental costs annually. "Fluoride is the perfect example of helping people without them even having to do anything," said Dr. Sreenivas Koka, former dean of the University of Mississippi Medical Center's school of dentistry. But an anti-fluoride movement has been gaining steam in recent years, with more than 170 communities across the U.S. rejecting fluoridated water since 2010 over health fears. In Florida alone, at least 24 cities and counties have ended fluoridation since September. Last week, Utah became the first state to ban the addition of the mineral to public water, with Republican Gov. Spencer Cox claiming there isn't sufficient evidence "to require people to be medicated by their government."

Is fluoride dangerous?

Too much fluoride—a naturally occurring mineral in soil, water, and rocks—can be a bad thing, causing skeletal fluorosis. But to develop that extremely rare bone-weakening condition, you'd need to consume more than 30 times the fluoride normally found in fluoridated water. Without clear scientific evidence of harms, opposition to fluoridation was long rooted in conspiracy theories: In the 1960s, the far-right John Birch Society claimed fluoridation was a communist mind-control plot. The anti-fluoride campaign moved from the political fringe to the mainstream amid the pandemic, part of a wider backlash against public health measures. In the days before the 2024 election, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—an anti-vax activist who is now health secretary—called the mineral "an industrial waste" and vowed the incoming Trump administration would recommend its removal from public water systems. The movement has been further supercharged by recent research suggesting risks to children from higher levels of fluoride.

What does that research say?

A study in May found that women who had higher levels of fluoride in their urine during pregnancy were more likely to report that their children went on to experience temper tantrums, suffer anxiety, and complain of headaches and stomachaches. "Our results do give me pause," said study author Tracy Bastain of the University of Southern California. "Pregnant individuals should probably be drinking filtered water." But some scientists call the study flawed, noting it involved a small sample of 229 women and relied on a single urine sample taken once during pregnancy, which is not sufficient to prove true fluoride overexposure. A few months later, a report from the federal National Toxicology Program that combined data from 74 studies concluded "with moderate confidence" that higher fluoride exposures "are consistently associated with lower IQ in children." The report didn't quantify the exact effects, but some of the studies showed a drop of a few IQ points with exposure above 1.5 milligrams of fluoride per liter of water. While that might seem like a bombshell finding, many researchers say the paper should not worry Americans who drink fluoridated water.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why not?

Critics note that more than two-thirds of the studies examined were deemed by the report's authors to have a "high risk of bias," undermining their reliability. More importantly, most of the data dealt with exposure levels far above those common in the U.S., where the Department of Health and Human Services recommends 0.7 milligrams of fluoride per liter—equivalent to about three drops of fluoride in a 55-gallon barrel. Only seven of the studies looked at children whose drinking water was below 1.5 milligrams per liter; in those studies, there was no relationship between IQ and fluoride. "The science is not as strong as it's presented by [the report's] authors," said Steven Levy, a dental public health expert at the University of Iowa. Despite those problems, the report's contents were given "substantial weight" in a September ruling from a federal court ordering the Environmental Protection Agency to address potential risks from fluoridation to infants.

Are there alternatives to fluoridating water?

Critics say the wide availability of fluoride toothpaste and mouthwash means there's no need to add the mineral to public water systems. But the Centers for Disease Control argues that a combination of fluoridated water and dental products containing fluoride provides the greatest protection against tooth decay, and fluoride advocates say dental products aren't accessible to everyone—especially low-income Americans. "Many kids tell us that they don't even have their own toothbrush," said Dr. Scott Tomar of the University of Illinois Chicago, who runs school-based dental programs.

What happens without fluoride?

Dentists warn that ending water fluoridation will lead to a decline in America's dental health. That's exactly what happened in Buffalo, after the city quietly stopped adding fluoride in 2015 while upgrading equipment at a water treatment facility. Few residents knew about the change until a local newspaper reported on it in 2023; local dentists said it explained why they had seen a sharp rise in cavities among the city's children in recent years. "What always gets me," said Jennifer Meyer, a nurse and professor of health sciences at the University of Alaska, is that the anti-fluoride activists aren't "at the bedside while that kid is getting a procedure to deal with extensive tooth decay, or an extraction or full mouth reconstruction in the operating room. But health care, public health, dental professionals are."

Going rogue on fluoride in Vermont

When Katie Mather's kids got their first cavities in 2022, her dentist said she didn't need to buy supplemental fluoride products since the water in their small town of Richmond, Vermont, had enough of the mineral. But that wasn't the case—the local water and sewer superintendent had lowered fluoride levels some four years earlier without telling anyone in the town of 4,100. Kendall Chamberlin eventually confessed, saying he didn't find Vermont's recommended fluoridation level of 0.7 milligrams per liter warranted and that he had lowered Richmond's to 0.3 milligrams. He also claimed there were quality issues with the fluoride because it came from China. "To err on the side of caution is not a bad position to be in," Chamberlin said. But Richmond's residents disagreed, and Chamberlin resigned in opposition to the town's decision to lift its fluoride back to the state's recommended level. "It's the fact that we didn't have the opportunity to give our informed consent that gets to me," said Mather.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Political cartoons for February 10

Political cartoons for February 10Cartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include halftime hate, the America First Games, and Cupid's woe

-

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?Today’s Big Question Government requested royal visit to boost trade and ties with Middle East powerhouse, but critics balk at kingdom’s human rights record

-

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depth

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depthTalking Point Emerald Fennell splits the critics with her sizzling spin on Emily Brontë’s gothic tale

-

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviews

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviewsTalking Points The guidelines emphasize red meat and full-fat dairy

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’

-

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

Choline: the ‘under-appreciated’ nutrient

Choline: the ‘under-appreciated’ nutrientThe Explainer Studies link choline levels to accelerated ageing, anxiety, memory function and more

-

How music can help recovery from surgery

How music can help recovery from surgeryUnder The Radar A ‘few gentle notes’ can make a difference to the body during medical procedures

-

Vaccine critic quietly named CDC’s No. 2 official

Vaccine critic quietly named CDC’s No. 2 officialSpeed Read Dr. Ralph Abraham joins another prominent vaccine critic, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.