The pros and cons of affirmative action

Even before the Supreme Court struck it down, affirmative action was a highly divisive practice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It has been over two years since the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed affirmative action in college admissions, a decision that thrust some of the country's most elite colleges and universities into the spotlight. This marked a drastic change from a decadeslong practice at U.S. colleges; American universities were permitted to consider race as a factor in admissions starting in 1978. But during this time, affirmative action also saw its fair share of controversy. Supporters argue that such policies — also known as positive discrimination — level the playing field for historically disadvantaged groups, but critics claim they unfairly discriminate and should be illegal.

Pro: boost for education

"Since nine states already have bans on affirmative action, it's easy to know what will happen if affirmative action is outlawed," Natasha Warikoo, a Tufts University professor who studies racial equity in education, said at The Conversation before the Supreme Court ruling. Studies on college enrollment in those states indicate that the number of Black, Hispanic and Native American undergraduate students will decline in the long term.

For example, after California banned affirmative action in state universities, the percentage of underrepresented minorities at UCLA dropped from 28% to 14% between 1995 and 1998. Nationwide, white students "made up 91% of college enrollment. In 2021, that number decreased to about 50%, with Black students accounting for 12.6% of college enrollees, Hispanic students 21.4%, and Asian students 7.1%," said the NAACP.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Universities may lose out from the ditching of such policies, said Jennifer Lee, a sociology professor at Columbia University, at Science.org. The result of the Supreme Court ruling will ultimately be "institutions that are less representative, less intellectually stimulating, and less equipped to serve an increasingly diverse America."

A year after affirmative action was struck down, colleges began releasing admissions data for the class of 2028, the first class to be impacted by the decision. But with only a few dozen schools reporting their enrollments, "we still can't definitively speak to how racially diverse this first post-affirmative action class will be," Michaele Turnage Young of the Equal Protection Initiative at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund said to Vox. So far, "there isn't much good news in the data for students of color," Vox said. Many schools have "yet to implement race-neutral policies aimed at fostering diversity in their classes, which would comply with the Supreme Court's decision."

Con: a form of discrimination

Advocates often argue that affirmative action is necessary to correct historical injustice and that discrimination against some groups is so pervasive that it can only be corrected with reverse discrimination.

But "critics of affirmative action argue that two wrongs do not make a right; that treating different racial groups differently will entrench racial antagonism and that societies should aim to be color-blind," said The Economist. Even as far back as 1996, it was being argued that "rather than fostering harmony and integration, preferences have divided the campus" along racial lines, said Stanford Magazine. This represents a "fundamental unfairness and arbitrariness of preferences" between white students and Black students.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In two lawsuits against Harvard and the University of North Carolina heard by the Supreme Court, the conservative-backed Students for Fair Admissions group argued that allowing colleges and universities to use race as a factor in deciding admission infringes civil rights legislation and is unconstitutional because it is discriminatory.

In ruling that race-based affirmative action programs in higher education violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, the Supreme Court agreed and "it was right to do so," said The Economist.

Pro: improves productivity

High-profile companies, including Apple, Starbucks and Ikea, joined together to file briefs at the Supreme Court arguing that racial diversity improves decision-making at their companies, said NPR's Mary Louise Kelly on "All Things Considered." Similarly, a "bunch of big law firms also weighed in on the value of a racially diverse pool of talent coming in to them."

The same has proved to be the case in the military, according to Travis Knoll, a historian at the University of North Carolina. At The Conversation, Knoll cited the Vietnam War, during which racial tensions in the ranks stemming from a lack of Black officers "led to at least 300 fights in a two-year-period that resulted in 71 deaths." This "drove home to the military the idea that diversity in leadership was extremely important" and "also began the military's use of affirmative action," including race-conscious admissions policies at service academies and in Reserve Officers' Training Corps programs.

Now that the Supreme Court has declared affirmative action policies in college and university admissions unconstitutional, "questions are arising over whether the court’s decision will affect diversity efforts in the workplace" and elsewhere, said Lauren Aratani at The Guardian.

Con: increases class inequalities

Somewhere along the decades, affirmative action "has lost its way," said law experts Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor Jr. at The Atlantic. "The largest, most aggressive preferences are usually reserved for upper-middle-class minorities on many of whom they inflict significant academic harm," they added, "whereas more modest policies that could help working-class and poor people of all races are given short shrift."

"We want diverse stock traders, corporate-boardroom members, and tenured professors," said Jay Caspian Kang at The New Yorker, but "it's clear that what's at stake isn't a vision of social and racial justice that would ameliorate inequalities for a broad swath of people but, rather, a fight for spots in the elite ranks of society."

"I think there's a better way than what we have now," a Harvard student named only as Kyle said to Fox News. "You have people of color who actually come from really privileged families, and they're getting benefited from this program, when you have people from other races who might not have any privilege in their background, and they don't benefit from it."

"Affirmative action betrayed Black America," said Inaya Folarin Iman at The Telegraph. "Far from addressing long-standing structural inequalities, it institutionalized the deeply racist idea that Black people were incapable of attaining positions of excellence and high achievement on merit alone." It suggested that "only through reliance on paternalistic white offerings could they ever succeed."

Pro: backed by public

Polls show that affirmative action policies have become increasingly accepted over time. Gallup polling found that public support in the U.S. stood at between 47% to 50% between 2001 and 2005 before climbing to 54% in 2016 and then 61% in 2018. A poll by Quinnipiac University in 2020 of more than 1,300 people found that two-thirds believed that discrimination against Black people in the U.S. was a serious problem.

But there are also people who are unfamiliar with the concept as a whole. A June 2023 Pew Research Center poll, released days prior to the Supreme Court's decision, found that 20% of Americans hadn't heard of affirmative action. But of those who had heard of it, the feelings were mostly positive, with 36% saying affirmative action was a "good thing."

Con: not cost effective

Critics question whether the costs associated with affirmative action policies, such as grants and scholarships to help access higher education, could be better spent improving opportunities for a wider demographic.

"The staggering cost of the diversity bureaucracy contributes to the rising cost of tuition," said Peter Kirsanow, a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, at the National Review in 2011. "Consequently, all students (or their guarantors/creditors) are paying more money/incurring greater debt so that preferred minority students will have a higher probability of flunking out."

Others, still, have proposed a different type of affirmative action, based not on race but on class and wealth. Under this type of program, colleges "would need to give a substantial admissions advantage to low-income applicants, enrolling a large number of students on this basis, to maintain the current representation of Black and Latino students," said the Brookings Institution. But as with race-based affirmative action, this too has generated controversy.

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterparts

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterpartsThe Explainer While Harvard is still near the top, other colleges have slipped

-

How Mississippi moved from the bottom to the top in education

How Mississippi moved from the bottom to the top in educationIn the Spotlight All eyes are on the Magnolia State

-

Oklahoma fires instructor over gender essay grade

Oklahoma fires instructor over gender essay gradeSpeed Read

-

Education: More Americans say college isn’t worth it

Education: More Americans say college isn’t worth itfeature College is costly and job prospects are vanishing

-

The Trump administration’s plans to dismantle the Department of Education

The Trump administration’s plans to dismantle the Department of EducationThe Explainer The president aims to fulfill his promise to get rid of the agency

-

How will new V level qualifications work?

How will new V level qualifications work?The Explainer Government proposals aim to ‘streamline’ post-GCSE education options

-

England’s ‘dysfunctional’ children’s care system

England’s ‘dysfunctional’ children’s care systemIn the Spotlight A new report reveals that protection of youngsters in care in England is failing in a profit-chasing sector

-

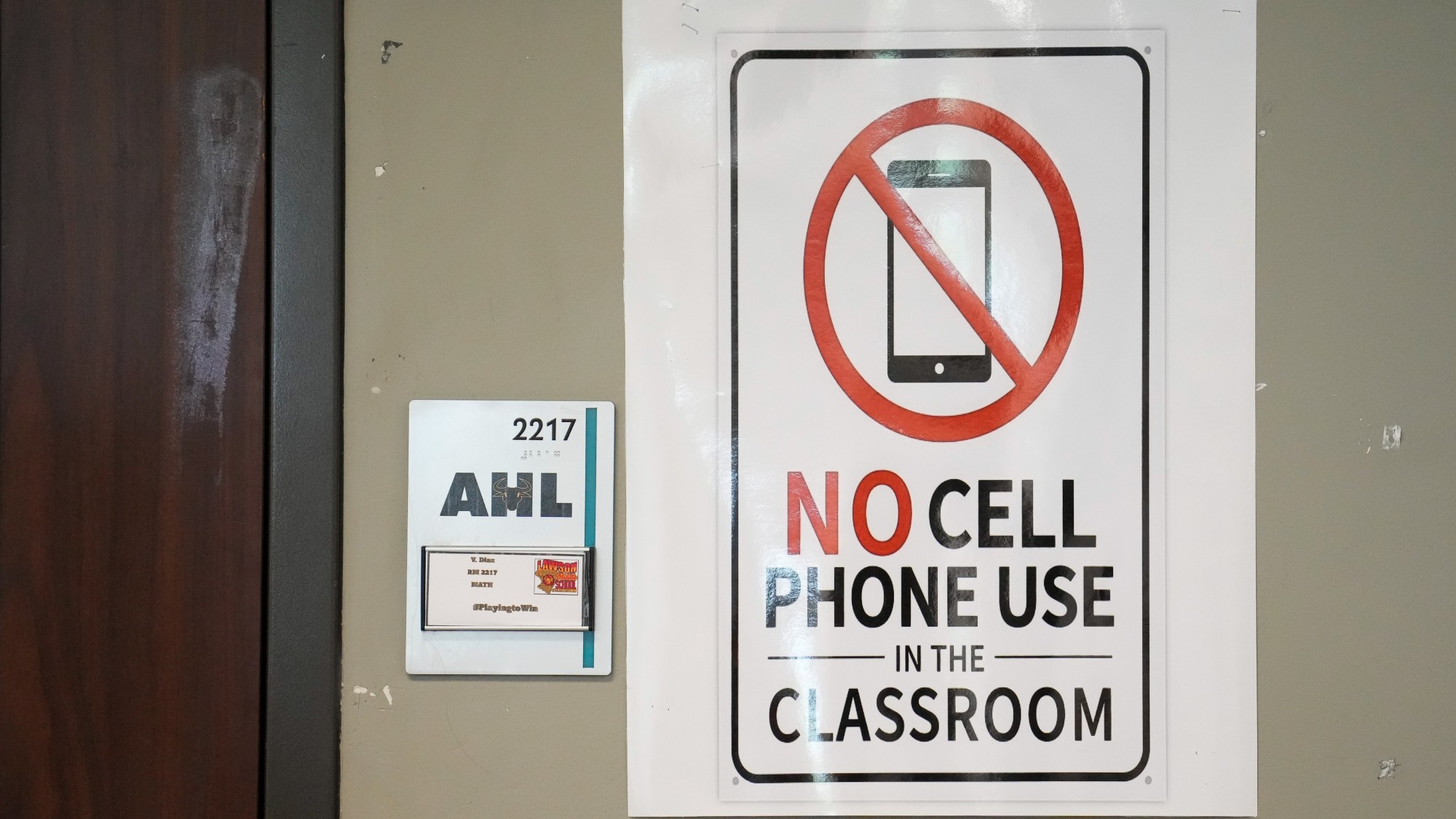

The pros and cons of banning cellphones in classrooms

The pros and cons of banning cellphones in classroomsPros and cons The devices could be major distractions