Will the fall of Afghanistan create a refugee backlash in the West?

UK government forced to ‘overhaul system’ as resettlement plans begin to draw criticism

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Thousands of Afghans are scrambling to escape the country after the Taliban last week regained control of Afghanistan following two decades of US occupation.

A UN report has warned that the insurgents’ power grab may mean that up to half a million Afghans could flee the country by the end of the year, urging neighbouring countries to keep their borders open in order to facilitate safe passage.

However, the mass movement of refugees fleeing the Taliban’s rule could set the scene for a “looming political controversy” in the West, Politico said, with countries already facing pressure over how many Afghans they will resettle – and when.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Refugees crisis 2.0

According to UN estimates, there are currently around 2.2m Afghan refugees already in neighbouring countries and 3.5m people that have been forced to flee their homes within Afghanistan’s borders due to the Taliban’s rapid spread across the country.

The sudden displacement of such large numbers of people, however, has already evoked memories of the 2015 refugee crisis, during which around 362,000 refugees crossed the Mediterranean Sea in attempts to reach Europe due to dangers in their home countries.

That influx of refugees helped trigger a populist backlash across Europe, damaging the political prospects of many social democratic parties and popularising the term “fortress Europe” to describe the response of many EU nations.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The UK government has already moved to “revamp its system for processing Afghan asylum applications after more than two weeks of chaos”, reported The i, with “at least four government departments…involved in operating the two settlement schemes which apply to Afghan civilians fleeing their home country”.

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace this week told a meeting of MPs that “officials were dealing with thousands of messages about people who have been left behind despite the evacuation of 15,000 Britons and Afghans in August”.

He also said that “civil servants would be unable to respond to each message in less than a week” amid claims that individual MPs are already “dealing with several thousand individual cases between them”, the paper added.

Similar disorder has also reared its head in the US, where Joe Biden has been hit with two waves of criticism, first for “abandoning Afghan partners as their country fell to the Taliban” and second over “the thousands of Afghans he will end up resettling”, Politico said.

With one eye on the midterms next year, “an increasingly vocal group of Republicans” have set about opposing “the resettlement of Afghan refugees in the US, claiming that they could be dangerous, or will change the make-up of the country”.

The Biden administration is “moving swiftly to try and tamp down any backlash”, the site added, focusing on “avoiding the sort of politicisation and outrage that plagued efforts to resettle Syrian refugees in 2015 and created havoc in the federal refugee program”.

According to Bloomberg correspondent-at-large Alberto Nardelli, the EU has already “floated a plan to spend €300m (£257.6m)” on its effort to resettle Afghan refugees in a plan that it hopes will “avert a migration crisis” like the one seen in 2016.

A diplomatic note seen by Nardelli shows the European Commission made the proposal during a meeting on 26 August, with a statement by the bloc’s executive arm later saying: “The EU will engage and strengthen its support to third countries, in particular the neighbouring and transit countries, hosting large numbers of migrants and refugees.”

The statement continued that the EU “will also cooperate with those countries to prevent illegal migration from the region”.

Germany, which led the effort to resettle refugees five years ago, has warned the EU against “following the UK’s lead in setting a target number of refugees from Afghanistan to be resettled in the union”, The Guardian said, “claiming it will act as a pull-factor”.

German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer told a meeting of the bloc’s home and justice ministers that he does not “think it’s wise if we talk about numbers here, because numbers obviously trigger a pull-effect and we don’t want that”.

However, the paper added that he also stressed the need for “a common EU asylum policy” despite “the reluctance of countries such as Austria”, warning that anything else would “risk a new migration crisis”.

His intervention came after Luxembourg’s foreign minister, Jean Asselborn, “risked the wrath” of the country’s EU allies by suggesting that the bloc should follow the UK’s example and set a figure for the amount of Afghan refugees it will resettle.

“It can’t be just the UK that has pledged 20,000 settlements,” Asselborn said. “Europe must also go in that direction.

“In 2015, with the Syrian crisis, the EU faced a problem and we were not prepared. That’s clear. Six years later, we are less prepared to face this problem than in 2015. It’s terrible to say so.”

Popular backlash

European support for refugees is “a fraught topic in the bloc”, said Bloomberg’s Nardelli, adding that “several member states are firmly opposed to accepting any migrants”. And Biden faces a similar challenge in the US, with attacks on refugees “serving as one of the pillars of Trump’s successful run for the presidency in 2016”, reported Politico.

When former president Barack Obama committed to a plan to resettle 10,000 refugees from Syria during that country’s civil war, “30 governors, all Republicans except one, tried to ban refugees from that country from entering their states”, the site noted.

At the time, Obama responded by saying that “we are not well served when, in response to a terrorist attack, we descend into fear and panic”, adding: “We don’t make good decisions if it’s based on hysteria or an exaggeration of risks.”

Research on Germany’s resettlement of one million refugees between 2014 and 2015 by the Washington-based Brookings Institute has found that “the channels through which terror and crime affect the West are overwhelmingly homegrown”, noting that refugees are in fact more likely to be victims of violence rather than the perpetrators.

The study said that “banning the displaced and migrants will have little impact on this challenge”, citing a study by the libertarian Cato Institute that found “all immigrants are less likely to be incarcerated than natives relative to their shares of the population”.

But despite that, the EU and US face a mounting challenge in terms of processing and welcoming refugees. Like UK Defence Secretary Wallace, the White House “has acknowledged the politics of bringing refugees to the US will be tricky”, Politico said.

However, Press Secretary Jen Psaki appeared bullish when addressing reporters this week, saying: “We also know that there are some people in this country, even some in Congress, who may not want to have people from another country come as refugees to the United States. That’s a reality.

“We can't stop or prevent that on our own… And we’re going to continue to convey clearly that this is… part of the fabric of the United States and not back away from that.”

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

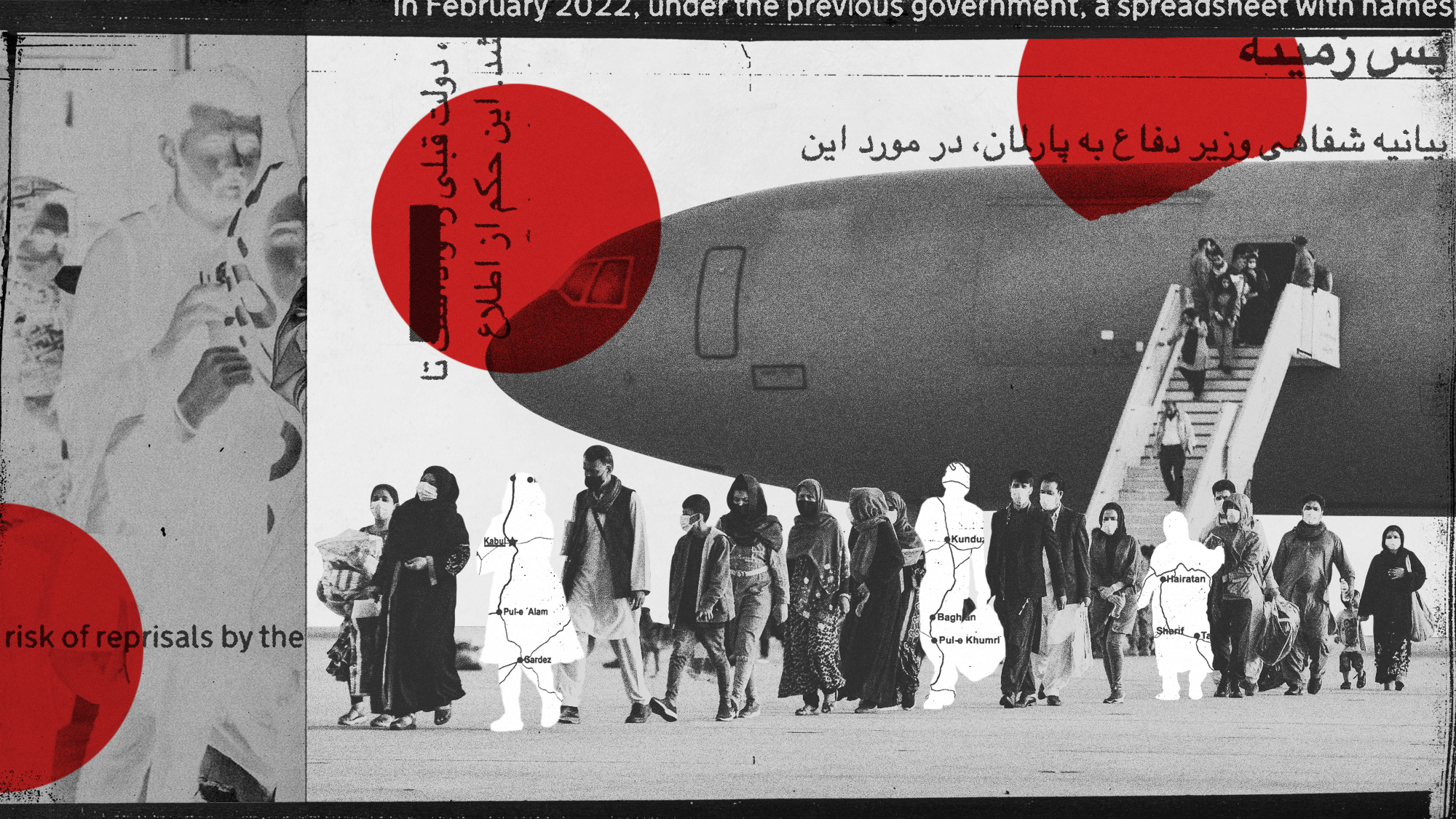

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation scheme

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation schemeThe Explainer Massive data leak a 'national embarrassment' that has ended up costing taxpayer billions

-

Israel's wars: is an end in sight – or is this just the beginning?

Israel's wars: is an end in sight – or is this just the beginning?Today's Big Question Lack of wider strategic vision points to 'sustained low-intensity war' on multiple fronts

-

Middle East crisis: is there really a diplomatic path forward?

Middle East crisis: is there really a diplomatic path forward?Today's Big Question Recent escalation between Israel and Hezbollah might have dented US influence in the conflict

-

The African asylum seekers fighting for Israel in Gaza

The African asylum seekers fighting for Israel in GazaUnder the Radar 'Quid pro quo' recruitment offer condemned as unethical as Israel seeks to address shortage of soldiers

-

Missile escalation: will long-range rockets make a difference to Ukraine?

Missile escalation: will long-range rockets make a difference to Ukraine?Today's Big Question Kyiv is hoping for permission to use US missiles to strike deep into Russian territory

-

Who would fight Europe's war against Russia?

Who would fight Europe's war against Russia?Today's Big Question Western armies are struggling to recruit and retain soldiers amid fears Moscow's war in Ukraine may spread across Europe

-

Are Ukraine's F-16 fighter jets too little too late?

Are Ukraine's F-16 fighter jets too little too late?Today's Big Question US-made aircraft are 'significant improvement' on Soviet-era weaponry but long delay and lack of trained pilots could undo advantage against Russia

-

Hamas and Hezbollah strikes: what does it mean for Israel?

Hamas and Hezbollah strikes: what does it mean for Israel?Today's Big Question Iran vows revenge for death of Hamas political leader in Tehran, hours after Israeli strike kills top Hezbollah member in Beirut