Twenty years of Guantánamo: can Biden finally close the US prison camp?

Of 780 total detainees, only 12 have ever been charged, and two convicted

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The US has had a presence in Guantánamo Bay, on Cuba’s southeast coast, since the Spanish-American war of 1898, when marines landed there to remove the island from Spanish colonial control.

Five years later, a nominally independent Cuban government leased the site to the US as a naval base. The US continues to pay for the lease – an annual cheque for $4,085 – but Cuba hasn’t accepted the funds since 1959, when Fidel Castro took power, and it regards the base as illegally occupied.

How did prisoners end up there?

In the early 1990s, the US often intercepted Cuban refugees at sea before they could claim asylum. They were held at Guantánamo, and litigation concerning them seemed to confirm that the base was outside US jurisdiction.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This made it an attractive option when George W. Bush launched the “Global War on Terror” in response to the 9/11 attacks in 2001, when the US was desperate to obtain information from captured terrorists – and was prepared to “work the dark side”, as the then vice-president Dick Cheney put it.

The Bush administration held that US legal protections didn’t apply to al-Qa’eda or Taliban prisoners, but it didn’t want to test this theory on US soil. As a result, 100 wire cages were erected in just 96 hours at Guantánamo, which received its first detainees – 20 men captured in Afghanistan – on 11 January 2002, four months to the day after the destruction of the World Trade Centre.

How did the world learn about the camp?

The Pentagon announced it, and released a soon-famous picture of the new arrivals kneeling in orange jumpsuits, blackout goggles and shackles, which was taken by a US navy photographer. Guantánamo was meant to be the military’s showpiece detention camp, housing “the worst of the worst”, as its first commandant, General Michael Lehnert, put it.

A spokeswoman for then secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld released the photo because she thought it would assure the world the detainees were being well treated. It had precisely the opposite effect. As the camp filled up – Guantánamo has handled roughly 780 people since 2002, 15 minors among them – it became an international byword for the follies and excesses of the War on Terror.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How bad was it?

The wire cages were soon replaced by cells made from shipping containers. Later, more conventional prison facilities appeared. By 2010, conditions were comparable to those in supermax prisons in the US. In its early years, however, prisoners were subjected to beatings, sleep deprivation, sexual abuse and humiliations, and other “enhanced interrogation techniques”, though the most extreme sessions took place at CIA “black sites” (unofficial jails) elsewhere.

In June 2004, the International Committee of the Red Cross issued a confidential report saying that treatment of the detainees in Cuba was “cruel, unusual and degrading”, amounting to “a form of torture”. In 2009, Susan Crawford, a Bush administration official, conceded that torture had been carried out there. There have been numerous hunger strikes and cases of self-harm; and seven apparent suicides.

Who were the prisoners?

Early on, Rumsfeld complained in a memo that the camp was filled with “low-level enemy combatants”. In fact, in 2006, a study of 517 detainees found that 55% had not even been determined to have committed any hostile acts against US forces or their allies; only 8% had been clearly identified as al-Qa’eda operatives.

Most had been captured in Afghanistan, where the US had offered big rewards – “enough to feed your family for life”, as one leaflet put it – in return for “Arab terrorists”. As a result, foreign travellers and people’s personal enemies were swept into the net.

However, in 2006, a number of “high-value detainees” were rendered there from CIA black sites, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged architect of the 11 September attacks, and Hambali, a member of the Indonesian Islamist group that carried out the 2002 Bali bombings.

Why hasn’t it been closed?

At the 2008 election, Barack Obama, John McCain and the outgoing President Bush all agreed that Guantánamo needed to be closed. Obama tried to, by executive order, on his second day in office. But foot-dragging by the Pentagon, Republican opposition and, arguably, Obama’s lack of political boldness, meant the effort failed.

There were overwhelming legal difficulties. Thanks to torture and the extra-legal nature of the enterprise, prisoners couldn’t be tried in civilian courts. The next-best solution, military tribunals, raised constitutional problems and lacked credibility.

At the same time, many prisoners couldn’t be repatriated, either because they’d be in danger in their home countries, or because they were seen as a security risk there. The Obama administration was reduced to bargaining with third countries to take them.

What’s the situation now?

Of 780 total detainees, only 12 have ever been charged, and two convicted (by military tribunals). The trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four others is now in its tenth year of pre-trial hearings. Under President Bush, 500 detainees were transferred out of the prison or released. Under Obama, 197 detainees were repatriated or resettled in third countries.

Under Trump, who promised to fill the site with “bad dudes”, one more was transferred. There are now 39 detainees at Guantánamo. President Biden also wants to close it, but has limited options: most Republicans still regard it, in Rumsfeld’s words, as “the least worst place” to keep such suspects. In theory, some could be tried by other countries. Legal avenues could be found for convicting others in the US. In the meantime, it will endure: the Pentagon has asked for $88m to build a hospice for ageing detainees.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

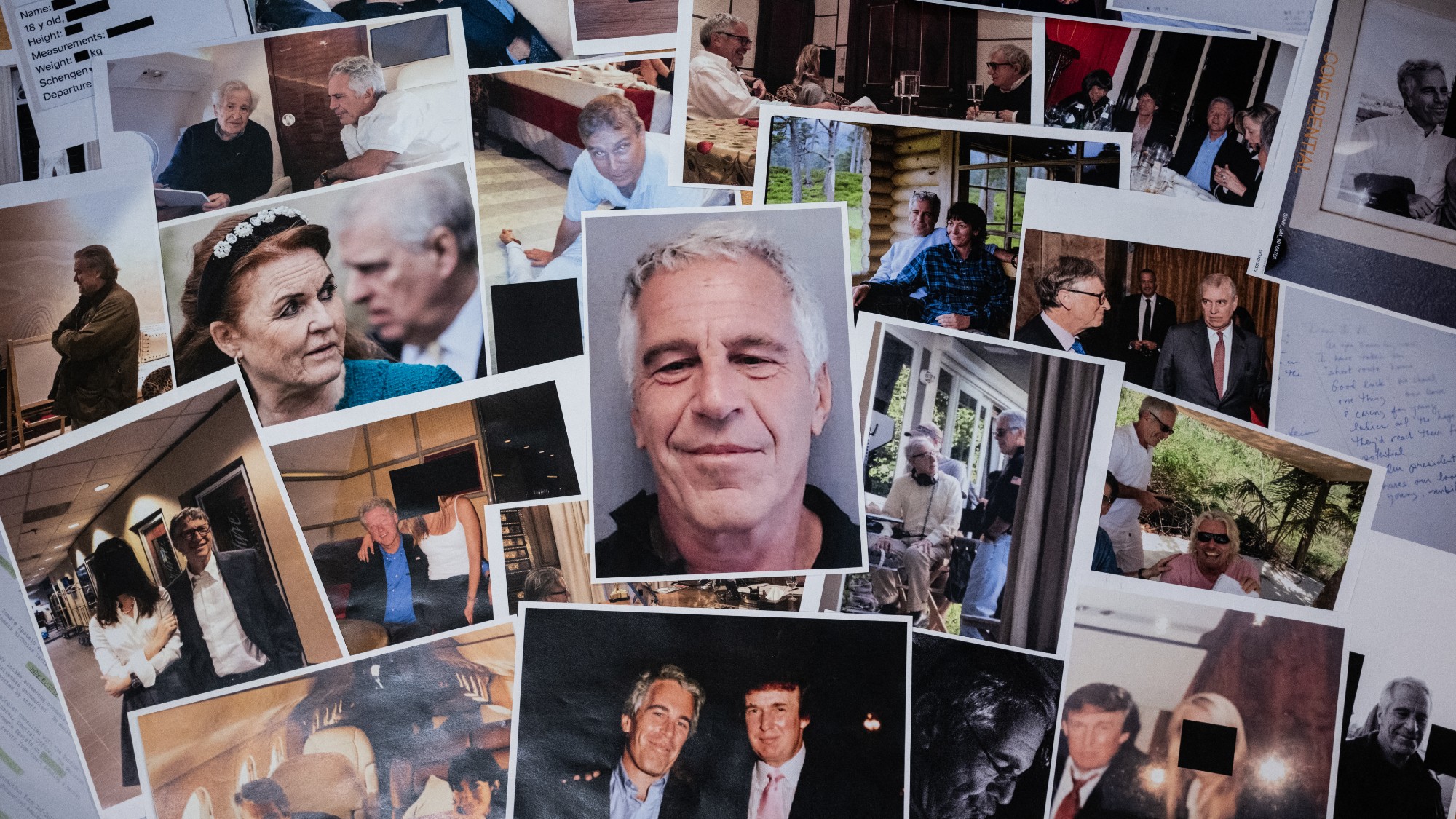

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing world

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing worldIn the Spotlight Trove of released documents paint a picture of depravity and privilege in which men hold the cards, and women are powerless or peripheral

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

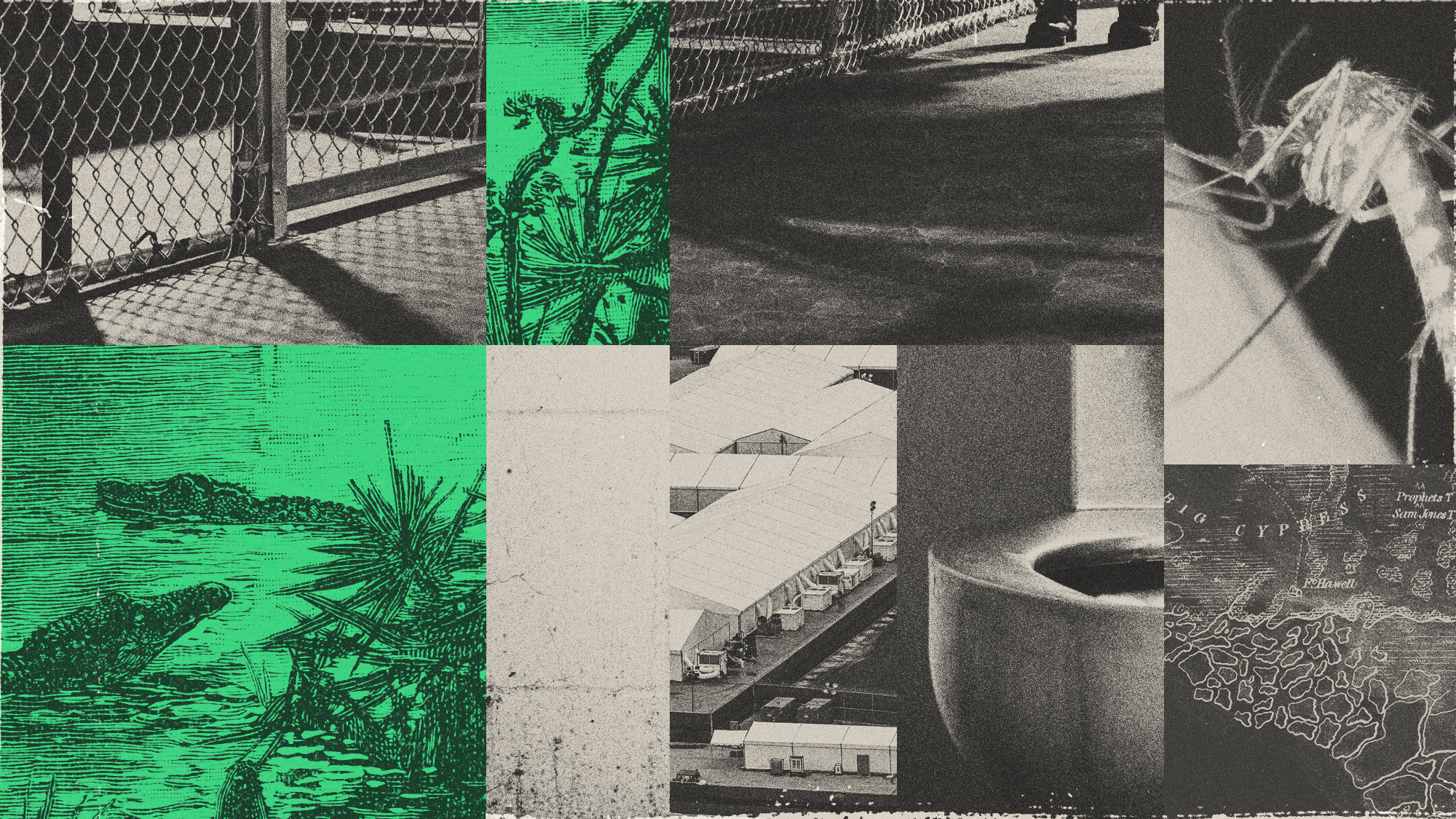

Insects and sewer water: the alleged conditions at 'Alligator Alcatraz'

Insects and sewer water: the alleged conditions at 'Alligator Alcatraz'The Explainer Hundreds of immigrants with no criminal charges in the United States are being held at the Florida facility

-

Diddy: An abuser who escaped justice?

Diddy: An abuser who escaped justice?Feature The jury cleared Sean Combs of major charges but found him guilty of lesser offenses

-

Crime: Why murder rates are plummeting

Crime: Why murder rates are plummetingFeature Despite public fears, murder rates have dropped nationwide for the third year in a row

-

The Sycamore Gap: justice but no answers

The Sycamore Gap: justice but no answersIn The Spotlight 'Damning' evidence convicted Daniel Graham and Adam Carruthers, but why they felled the historic tree remains a mystery

-

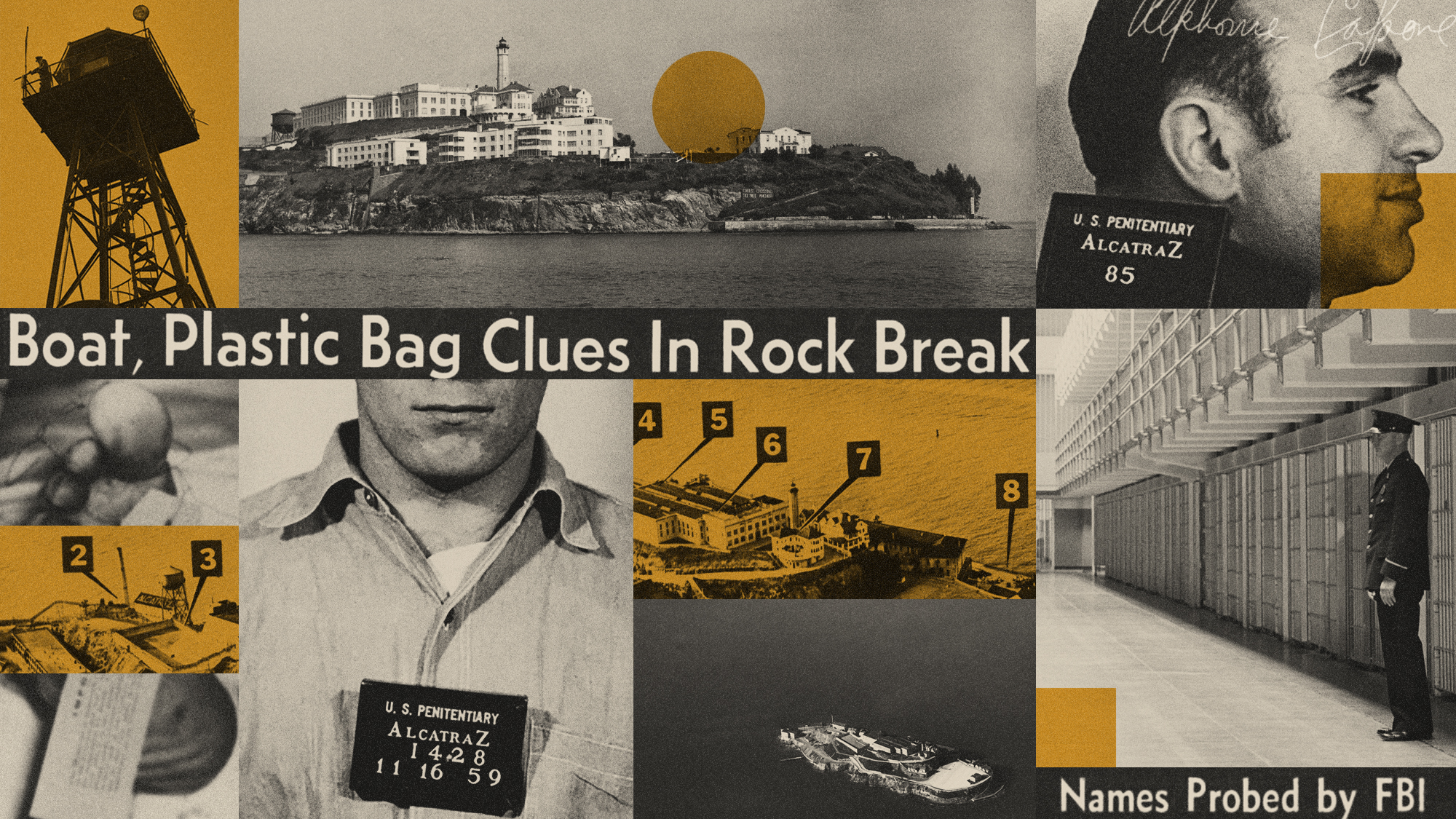

Alcatraz: America's most infamous prison

Alcatraz: America's most infamous prisonThe Explainer Donald Trump wants to re-open notorious 'escape-proof' jail for 'most ruthless and violent prisoners' in the US